Unraveling the NHS 111 Algorithm

Discover the intricacies of the NHS 111 algorithm, its impact on healthcare, and the future of urgent care services in England. This comprehensive guide explores the design, challenges, and improvements of the NHS 111 algorithm, along with statistical data and expert insights.

The NHS 111 service, underpinned by the sophisticated NHS Pathways algorithm, stands as a cornerstone of urgent and emergency care provision in the United Kingdom. Designed as a digital triage system, its primary objective is to streamline patient access to appropriate healthcare advice and services, thereby aiming to alleviate pressures on emergency departments and ambulance services. This report delves into the intricate operational mechanisms of the NHS 111 algorithm, its observed impacts on patient flow and resource utilization, and the critical challenges it faces, including concerns regarding accuracy, patient compliance, and systemic biases. It also examines the robust regulatory and governance frameworks in place to ensure patient safety and explores comparative insights from international digital triage systems. The analysis concludes with a set of recommendations aimed at enhancing the algorithm's effectiveness, promoting equitable access, and fostering a more integrated and responsive urgent care landscape.

The NHS 111 algorithm, powered by NHS Pathways, operates on a symptom-based, diagnosis-by-exclusion logic, prioritizing life-threatening conditions to ensure patient safety. While the online service demonstrates cost-efficiency at the point of contact, its broader impact on reducing demand for emergency services remains nuanced, with evidence suggesting persistent A&E attendances and ambulance dispatches. A significant challenge lies in patient non-compliance with advice and the capacity constraints within primary care, which can lead to patients escalating their concerns to higher acuity services. Furthermore, the algorithm faces scrutiny regarding inherent biases that can perpetuate health inequalities, particularly affecting older individuals, those with long-term conditions, and certain ethnic minority groups, exacerbated by issues of digital exclusion. Despite these challenges, a comprehensive regulatory framework, including medical device classification and stringent clinical safety standards, governs the system. The continuous evolution of NHS Pathways, driven by clinical evidence and stakeholder feedback, demonstrates a commitment to adaptive governance. Future enhancements are likely to leverage advanced AI to further optimize patient pathways and support clinical teams, necessitating continued vigilance over safety, equity, and system-wide integration.

2. Introduction: The Strategic Role of NHS 111 in UK Urgent and Emergency Care

Purpose and Scope of NHS 111 and NHS Pathways

The NHS 111 service serves as a vital, free, and accessible 24/7 urgent (non-emergency) care triage system within England, available via both a dedicated telephone line and an online digital platform (111.nhs.uk). This service is specifically tailored for individuals aged five and over, aiming to guide them through a series of questions about their symptoms. It is explicitly designed to offer appropriate self-care advice or, critically, to direct users to the most suitable urgent and emergency care services available. It is important to clarify that NHS 111 does not provide a definitive diagnosis; instead, its function is to advise users on the immediate next steps and the appropriate timeframe for action.The overarching goal is to enhance the speed and efficiency with which patients receive the necessary advice and treatment for both their physical and mental health concerns. The online platform, for instance, covers approximately 120 common symptom topics, capable of triaging one primary symptom at a time, with guidance for users to prioritize their most bothersome symptom if multiple are present.

The operational backbone supporting both the telephone and online NHS 111 services is the NHS Pathways algorithm, a sophisticated clinical decision support system (CDSS). The significance of NHS Pathways extends beyond NHS 111, as it is also an integral component of the 999 emergency services, Integrated Urgent Care Clinical Assessment Services (IUC CAS), and assists in the management of patients presenting at urgent care or emergency departments. The widespread application of NHS Pathways across these critical urgent and emergency care touchpoints suggests a deliberate strategic effort by NHS England to standardize initial patient assessment and referral processes. This pervasive adoption of a single clinical decision support system across multiple services is intended to foster a more integrated and coordinated urgent care system, aiming to reduce fragmentation and improve patient flow by ensuring consistent triage logic, regardless of a patient's initial point of contact. This foundational role in standardizing assessment pathways is crucial for achieving a "right place, first time" model of care across the broader healthcare system.

Historical Context and Evolution of the Service

The NHS 111 service is not a standalone innovation but rather the culmination of an evolutionary process in urgent care telephone services within the UK. It succeeded NHS Direct, a pioneering nurse-led telephone advice service that operated from 1998 to 2014. The transition to NHS 111 in England was completed by February 2014, with similar 111 services subsequently rolled out in Scotland and Wales.

The impetus for NHS 111 originated from the 2007 Department of Health report, "Our NHS, Our Future," which identified public confusion regarding access to various NHS services. The report proposed the introduction of a national, easily memorable three-digit number for out-of-hours healthcare, leading to the official allocation of the 111 number by telecommunications regulator Ofcom in December 2009.

Pilot programs for NHS 111 commenced in August 2010 in areas such as County Durham and Darlington, with a broader national launch initially slated for April 2013. However, this ambitious full rollout was met with significant apprehension from the medical community. The British Medical Association, through its then-chair Dr. Laurence Buckman, notably warned that the service was "a disaster in the making" and strongly recommended delaying the full launch due to patient safety concerns. Despite these criticisms, the service was gradually implemented across England, completing its rollout by February 2014, which coincided with the closure of NHS Direct.

The digital extension of the service, NHS 111 Online, was introduced in England in late 2017, leveraging the identical NHS Pathways algorithm used by the telephone service. More recently, in 2020, the "111 First" system was launched. This initiative allowed patients not in immediate medical emergencies to "book" urgent care appointments via 111, a direct and rapid response to the escalating pressures on emergency services during the COVID-19 pandemic. This historical trajectory, from a nurse-led service to one heavily reliant on a clinical decision support system, and its subsequent digital expansion, clearly illustrates a continuous strategic endeavor to leverage technology for managing urgent care demand. The initial, strong criticisms from professional bodies highlight the considerable challenges inherent in implementing large-scale digital health solutions. The swift introduction of "111 First" during the pandemic further underscores how external pressures can accelerate the adoption and adaptation of such digital tools. This iterative, often reactive, evolution, driven by both policy ambitions for efficiency and appropriate access, as well as emergent healthcare crises, reveals the dynamic and complex nature of integrating technology into a national healthcare system.

3. The NHS Pathways Algorithm: Structure and Functionality

Core Design Principles and Triage Logic

NHS Pathways is fundamentally a clinical tool engineered for the assessment, triage, and direction of the public to urgent and emergency care services. Its foundational structure comprises an "interlinked series of algorithms, or pathways," meticulously designed to connect clinical questions with appropriate care advice, ultimately leading to specific clinical endpoints, commonly referred to as "dispositions".

The system operates on a symptom-based approach rather than attempting to provide a definitive medical diagnosis. Users engage with the system by answering a series of questions about their primary symptom. Based on their responses, the algorithm determines the most suitable clinical response, outlining the recommended level of care and the timeframe within which that care should be sought. A crucial design element is the hierarchical arrangement of questions, which ensures that queries pertaining to life-threatening symptoms are presented early in the assessment process. A general principle observed is that the more questions a user is required to answer, the less severe their symptoms are likely to be, reflecting a progressive filtering mechanism.

NHS Pathways employs a "diagnosis of exclusion" model. This means the system systematically rules out potential conditions through a structured series of triage questions. These questions are developed and refined by a team of senior clinicians at NHS Digital. Upon reaching an illness or injury that cannot be excluded through this process, the system directs the patient to the appropriate level of care for that specific condition. The underlying principle guiding this design is that patients should theoretically always receive a level of care that is equivalent to or higher than their actual clinical need, thereby minimizing the risk of under-triage. This inherent safety-first approach, while paramount for high-stakes medical triage, carries an implicit trade-off: it can contribute to over-triage, where patients are directed to higher acuity services than might be strictly necessary. This potential for over-triage, a recurring concern within the service, is therefore not merely a flaw but a direct consequence of the algorithm's fundamental, safety-driven design philosophy.

The diverse range of outcomes generated by the algorithm is designed to cater to a broad spectrum of urgent care needs. These outcomes include: receiving a callback from a nurse; referral to urgent treatment centres; advice to see evening and weekend GPs; referral to specialist support for sexual or mental health; direction to Accident & Emergency (A&E) departments; advice to contact one's own GP surgery (during daytime weekday hours); guidance on finding dentists or opticians (including emergency options); referral to pharmacists for minor illnesses or emergency medicine supplies; and, for less serious conditions, self-care advice for managing symptoms at home.

Key Modules and Decision-Making Process

The NHS Pathways system is structurally divided into distinct modules, designed to manage the varying complexities of urgent and emergency care presentations efficiently. This modular approach is critical to its functionality.

Module 0: This serves as the initial entry point into the NHS Pathways system. Its primary focus is on identifying and addressing immediately life-threatening situations or commonly "declared" serious conditions, such as heart attacks, strokes, anaphylaxis, or severe blood sugar problems. Evidence suggests that for certain high-profile or well-understood conditions, callers are often accurate in their initial assumptions, allowing this module to provide a rapid means of assessing such urgent cases. If the responses to questions within Module 0 indicate sufficient severity, the system will automatically trigger the dispatch of an emergency ambulance, and no further questions or considerations of other conditions are needed at this critical juncture. While Module 0 rules out the most acute life-threatening conditions, it does not exclude all such possibilities.

Module 1: Once the immediate life-threatening conditions (or the most acute ones) have been addressed or ruled out in Module 0, the assessment seamlessly transitions to Module 1. This module begins by presenting a "body map," a pictorial representation of the human body tailored to the patient's age and gender. It contains a comprehensive array of questions that a Health Advisor may ask, with specific pathways available and selected based on the caller's reported main or most bothersome symptom. In situations where a single, clear main or worst symptom cannot be identified, the non-clinical Health Advisor is explicitly instructed to seek clinical advice. This instruction is a crucial design feature, acknowledging the inherent limitations of purely algorithmic assessment for ambiguous or complex patient presentations. It highlights a critical "human-in-the-loop" element, demonstrating that the system is designed with an awareness of its own boundaries, where human clinical judgment is considered indispensable for nuanced cases. This integrated approach is key to understanding the algorithm's practical application and its built-in safety nets.

Subsequent Progression: The questioning continues in a hierarchical order, with each answer determining the subsequent question asked. This iterative process continues until one of three outcomes is reached: a definitive endpoint (disposition) is determined, the call is ended prematurely, or the call is handed over to a clinician for more detailed assessment. The general rule is that the more questions asked, the less severe the symptoms are likely to be.

To ensure that patients are directed to available and appropriate services, the system leverages the Directory of Services (DoS). This integration is designed to refer patients to locally-commissioned services that best meet their needs, thereby aiming to reduce the phenomenon of patients "rebounding" between different care providers due to repeated re-triage. This improves the continuity and overall efficiency of care pathways.

Development and Clinical Content Methodology

NHS Pathways is owned by the Department for Health and Social Care and is delivered by the Transformation Directorate of NHS England. The development and meticulous maintenance of the system's clinical content are overseen by a dedicated team of experienced staff, the majority of whom possess a background in urgent and emergency care. A critical assurance is that all members of the clinical authoring team are registered, licensed practitioners, ensuring the clinical credibility and expertise essential for content development.

The process for developing clinical content is structured and methodical, adhering to a multi-stage approach. This includes a comprehensive initial assessment of existing pathways, the identification and prioritization of opportunities for improvement, and the development of a strategic vision for the service. This process integrates detailed data analysis with established best practices to inform content updates and refinements.

Independent oversight of the safety of NHS Pathways' clinical triage process endpoints is provided by the National Clinical Assurance Group (NCAG). This group comprises senior clinicians representing all relevant professional Colleges, ensuring impartial scrutiny and adherence to the highest clinical standards.

The clinical content undergoes continuous updates, driven by new or emerging clinical evidence, formal change requests, and direct feedback from service providers and wider stakeholders. These enhancements are specifically aimed at improving clarity for users, optimizing both user and patient experiences, and ultimately ensuring that the triage process remains as safe, effective, and efficient as possible. This continuous update cycle, informed by new clinical evidence, stakeholder feedback, and internal reviews, exemplifies a robust commitment to adaptive clinical governance. The involvement of registered, licensed practitioners in content authoring and the independent oversight by the NCAG provide multiple layers of clinical assurance. This iterative development model is critical for maintaining the algorithm's clinical relevance, accuracy, and safety in a rapidly evolving medical landscape, directly enabling the system to respond to new medical knowledge, address identified deficiencies, and adapt to emerging health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic which led to updates to reflect the need for patients with COVID-19 symptoms to be referred to specific clinical assessment services. Recent examples of such updates include revised guidance for pre-term resuscitation, adjustments to labour and childbirth pathways, refinements for repeat prescription requests, and enhancements for the management of patients with tracheostomies or laryngectomies. This proactive and reactive adaptation is a hallmark of a mature, responsible digital health system.

4. Operational Impact on the UK Healthcare System

Influence on Emergency Department (A&E) Demand and Ambulance Services

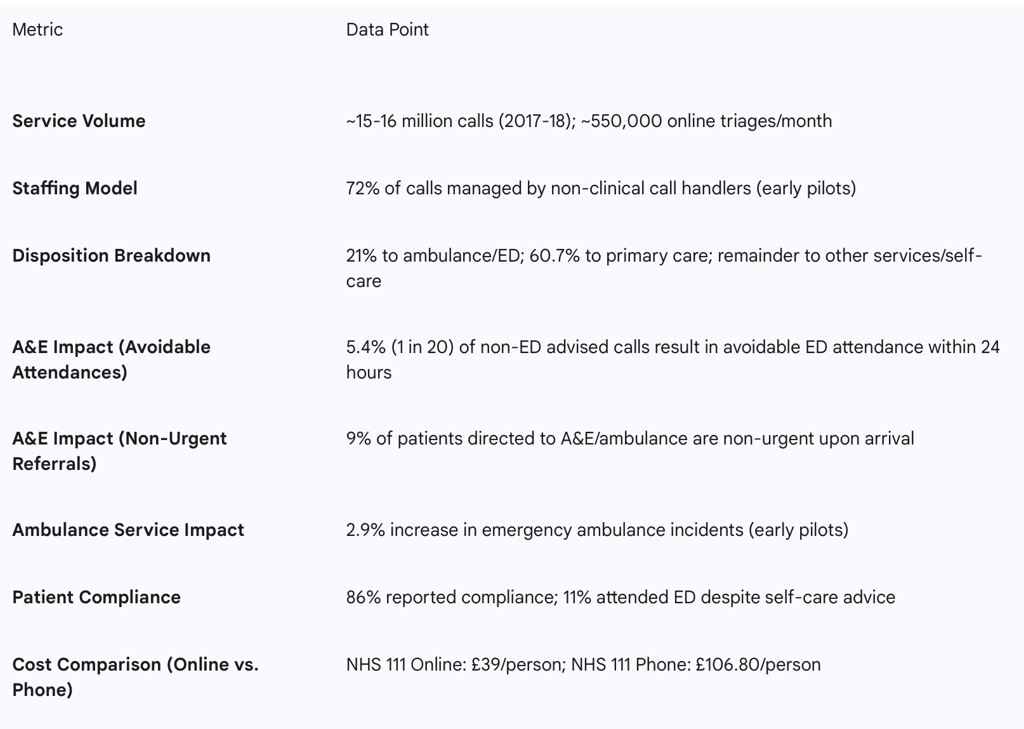

A primary anticipated benefit of the NHS 111 service was to alleviate pressure on emergency services by reducing unnecessary 999 calls and A&E attendances, thereby directing patients to the "right place first time". However, early evaluations of NHS 111 pilot sites in their first year of operation presented a complex picture, revealing no statistically significant impact on A&E attendance rates. Counterintuitively, some studies even indicated an increase in emergency ambulance incidents, with a 2.9% rise observed in early pilots. This suggests that the algorithm's direct triage output does not automatically translate into the desired system-wide efficiency gains.

A significant challenge identified is patient non-compliance with the advice provided by NHS 111. Research indicates that 11% of patients, despite being advised to self-care or seek primary care, still attended A&E within 24 hours. Alarmingly, 88% of these non-compliant patients were subsequently deemed to have urgent needs upon A&E assessment, and a considerable minority (37%) were admitted to hospital. This phenomenon leads researchers to suggest the occurrence of "many hundreds of thousands of mis-triaged cases annually". Conversely, 9% of patients who were directed to an ambulance or A&E by NHS 111 were later classified as non-urgent upon arrival, indicating instances of over-triage.

The role of clinical input within the NHS 111 service is notable in mitigating these issues. Studies have consistently shown that when a nurse or doctor provided assessment during or after NHS 111 calls, it was associated with lower rates of A&E attendances, particularly for children and young people. In direct response to these findings and ongoing concerns, NHS England increased the proportion of calls receiving clinical assessment from 23% in January 2017 to 39.5% in January 2018. The data therefore highlights that human clinical judgment is a crucial mediating factor in optimizing patient pathways and achieving system efficiency, implying that the algorithm's impact is heavily influenced by its interaction with human elements and patient behavior, rather than being a standalone solution.

Impact on Primary Care Workload and Patient Pathways

The NHS 111 service frequently directs callers to primary care services, with approximately 48% to 55% of all dispositions recommending contact with primary care. This represents a significant intended channel shift towards less acute settings, aiming to manage demand more appropriately across the healthcare system.

However, a critical challenge identified is that less than half of these callers actually establish contact with a primary care service. Furthermore, even when contact is made, the specified triage timeframes for follow-up are frequently not met, particularly for high-acuity cases where a one-hour timeframe is given, with only 37% of these being met. This suggests a significant mismatch between the demand generated by the NHS 111 algorithm and the current capacity or accessibility of primary care provision. This represents a "capacity-compliance conundrum," where the algorithm generates demand for primary care that the system cannot adequately meet, leading to patients escalating their concerns.

A concerning consequence of this unmet demand is that patients who were triaged to primary care but did not establish contact were more likely to subsequently call 999 or attend A&E. This "rebounding" effect directly undermines the initial goal of diverting patients from emergency services. The algorithm's effectiveness in optimizing patient flow is therefore severely limited by the real-world constraints of downstream service availability and the complex factors influencing patient behavior and trust. While the primary care disposition category includes various services such as pharmacists, opticians, and mental/maternity health services, these alternatives to traditional GP or Integrated Urgent Care (IUC) centres are often rejected by patients due to personal preference or by the services themselves due to capacity constraints.

Overall System Efficiency and Patient Flow Dynamics

The fundamental objective of NHS 111 is to enhance access to urgent care and improve overall system efficiency by ensuring patients are directed to the most appropriate care setting at the earliest opportunity. The service handles a significant volume of interactions, processing approximately 48,000 calls per day and around 550,000 online triages per month.

Despite this substantial activity, early evaluations indicated limited evidence that NHS 111 led to a decrease in demand for other NHS emergency and urgent care services. In fact, there was a potential for overall demand across the urgent care system to increase. From a cost perspective, NHS 111 Online is demonstrably more cost-effective per person compared to the telephone service, with an estimated cost of £39 per person for online versus £106.80 for telephone interactions. This difference is largely attributable to the lower initial contact cost: £1 for online versus £11 for telephone. The overall cost to the NHS is estimated to be £68 higher per person for the telephone service, influenced by subsequent service use patterns. It is important to acknowledge that this cost difference is partly attributed to the likelihood that online users present with less severe conditions, indicating a self-selection bias in the user base.

Economic analysis suggests that if 38% or more of NHS 111 Online contacts lead to a corresponding reduction in telephone calls, a parallel service model (combining online and telephone) could be more cost-effective than a telephone-only service. However, despite these potential cost savings at the point of triage, the service has had limited impact on reducing the overall demand for other NHS emergency and urgent care services. Some evidence even points to an increase in overall disposition recommendations (including ambulance, ED, and primary care) following the introduction of NHS 111 Online. This highlights a discrepancy between micro-level efficiency gains (e.g., cheaper online contacts) and macro-systemic impact. It implies that while the digital channel is more cost-efficient in its operation, it has not fundamentally altered the demand dynamics of the wider urgent and emergency care system. Gains in one area do not automatically translate to system-wide improvements without addressing underlying demand drivers and service capacity, and accounting for patient self-selection.

Table 1: Key Outcomes and Referral Patterns of NHS 111 Service

5. Challenges, Criticisms, and Limitations

Accuracy and Over-triage Issues

Despite its sophisticated design, persistent concerns surround the overall effectiveness of NHS 111, particularly regarding the appropriateness of the advice provided and the subsequent compliance of patients. Research indicates a substantial volume of "mis-triaged cases annually," potentially numbering in the hundreds of thousands. This includes a significant proportion (11%) of patients who, despite being advised by NHS 111 to self-care or seek primary care, subsequently attend A&E. Of these, a high percentage (88%) are later assessed as having urgent needs, and a considerable minority (37%) are admitted to hospital. Conversely, 9% of patients who are directed to an ambulance or A&E by the service are classified as non-urgent upon arrival, suggesting instances of over-triage.

A key criticism often centers on the role of non-clinical call handlers, who manage the majority of calls (72%). Studies suggest that these non-clinical triages are frequently "overly risk-averse," contributing to over-triage and potentially increasing the workload for already strained emergency services. When clinical input from a General Practitioner (GP) or nurse is provided during or after a call, it tends to be markedly less risk-averse and is associated with fewer A&E attendances. One study specifically noted that 74% of NHS 111 primary triage outcomes were "downgraded in urgency" following a clinician-led secondary triage, while 12% were "upgraded," raising legitimate concerns about the initial safety and accuracy of the primary triage. The consistent evidence of over-triage and mis-triage, despite the algorithm's safety-first design, highlights a fundamental paradox: prioritizing safety through a cautious algorithm can inadvertently lead to inefficiencies and increased burden on higher-acuity services. The fact that non-clinical call handlers, who process the majority of calls, are perceived as "overly risk-averse" suggests a critical interaction effect where the algorithm's inherent caution is compounded by the non-clinical staff's need to err on the side of safety. This indicates that the problem is not solely with the algorithm's logic but also with the operational model and the human-algorithm interface, where the lack of immediate clinical judgment at the first point of contact can lead to suboptimal resource allocation.

Patient Compliance with Advice and Satisfaction Levels

While initial patient satisfaction with NHS 111 was reported as high, and patients generally tended to comply with the advice given, it remains unclear whether these trends have persisted as the service has evolved and demand has increased.A significant challenge to the service's overall effectiveness is the frequent non-compliance with advice, as evidenced by the 11% of patients who attended A&E despite being advised to self-care or seek primary care.

Early pilot services reported "very good" overall satisfaction, with 73% of respondents indicating they were "very satisfied" and 91% reporting being either "very satisfied or satisfied". However, a notable discrepancy emerged when examining specific aspects of the service: users expressed lower satisfaction with the "relevance of questions asked" and the "accuracy and appropriateness of advice given" compared to other aspects of the service. This apparent contradiction between high overall patient satisfaction and lower satisfaction with the accuracy and relevance of advice, coupled with significant non-compliance rates, suggests a critical "trust-utility gap." Patients may appreciate the accessibility and convenience of the service, which contributes to high general satisfaction. However, if they perceive the questions as irrelevant or the advice as inaccurate, their trust in the clinical utility of the algorithm's output diminishes. This erosion of trust can lead to non-compliance, ultimately undermining the intended efficiency gains by redirecting patients to other, often more expensive, services. This highlights that perceived clinical validity and trust are as crucial as accessibility for the algorithm's overall success in guiding patient behavior.

Addressing Algorithmic Bias and Health Inequalities

Demographic Disparities (Age, Gender, Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status)

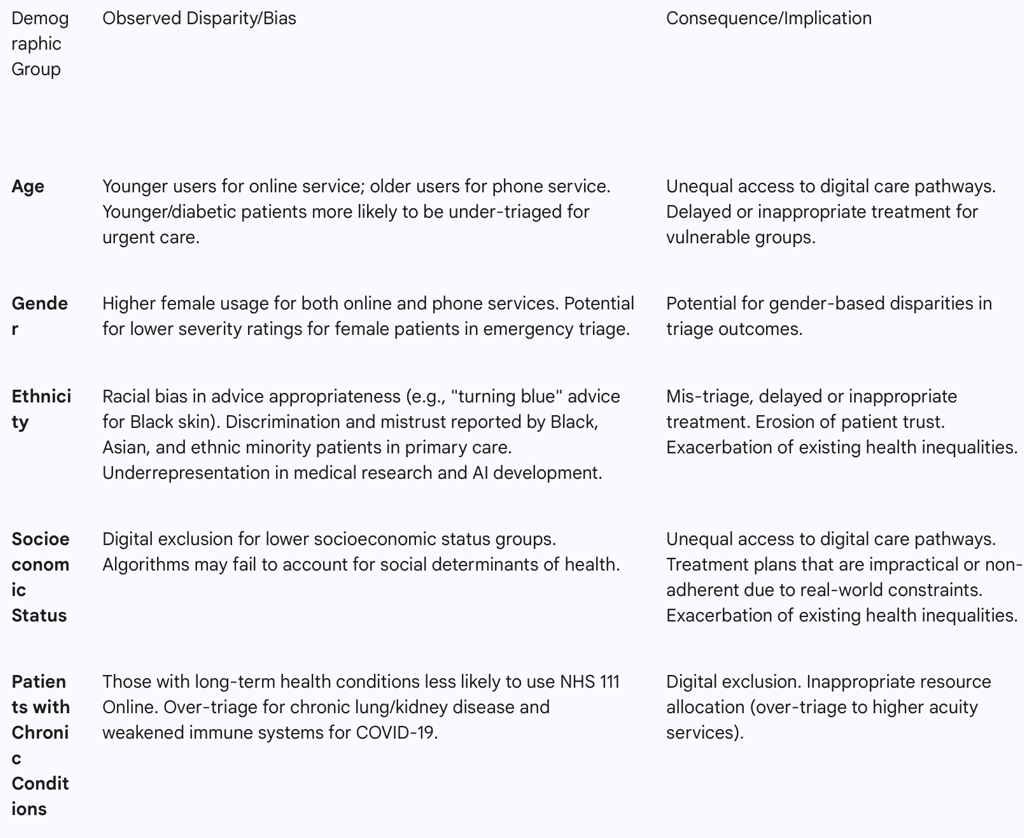

There are clear demographic disparities in NHS 111 usage patterns. NHS 111 Online users are predominantly younger, with over 60% aged 16-34, while less than 2% of users are aged 75 and over. In contrast, telephone users tend to be older.Both online and phone services also show a higher proportion of female users.

Research indicates that AI algorithms, including those increasingly used in healthcare, can inadvertently perpetuate biases embedded in historical training data. This can disproportionately impede healthcare for specific demographic groups, such as Black and Latinx patients, due to their underrepresentation in medical research and a lack of diversity among AI developers. Such biases can lead to misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, or recommendations that fail to account for crucial social determinants of health, such as access to transportation, healthy food, or work schedules.

A study examining COVID-19 triage via NHS 111 found that younger individuals and those living with diabetes were more likely to be incorrectly advised that they did not need urgent care (under-triage). Conversely, patients with long-term lung or kidney disease or weakened immune systems were more prone to being incorrectly given urgent care (over-triage). A survey on primary care services revealed alarming levels of discrimination and mistrust among Black, Asian, and ethnic minority patients, with 38% of Asian and 49% of Black participants reporting differential treatment based on ethnicity. Specific concerns included a perceived lack of medical competence and cultural awareness, exemplified by advice like monitoring "turning blue in the face," which is clinically inappropriate for assessing cyanosis in Black skin tones. Algorithmic bias can also contribute to existing disparities in healthcare outcomes, such as the nearly 30% higher overall mortality rate observed in non-Hispanic Black patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients. The convergence of evidence demonstrating demographic disparities in NHS 111 usage and the documented instances of algorithmic bias affecting specific patient groups based on age, chronic conditions, and ethnicity reveals a profound equity challenge. This goes beyond mere technical inaccuracy to highlight how the algorithm, if not carefully designed, trained, and monitored, can inadvertently exacerbate existing health inequalities. Biases, whether inherited from unrepresentative training data, amplified by the human-AI interaction, or stemming from a lack of cultural competence in the algorithm's logic, can lead to differential access, mis-triage, and a significant erosion of trust among already marginalized communities. This directly challenges the NHS's foundational principle of universal, equitable care, transforming a technological solution into a potential source of systemic inequity.

Digital Exclusion and eHealth Literacy

The strategic push towards "digital first" approaches, such as NHS 111 Online, carries a significant risk of exacerbating health inequalities due to inherent variations in eHealth literacy across the population. Studies confirm that NHS 111 Online users generally exhibit higher eHealth literacy scores compared to non-users. Demographic analysis further shows that individuals younger than 25 and those with formal qualifications are more inclined to use NHS 111 Online.Conversely, populations with long-term health conditions, lower socioeconomic status, and certain ethnic minority groups are less likely to engage with web-based health information or symptom checkers.

The strategic shift towards "digital by default" and the observed demographic patterns of NHS 111 Online usage (younger, higher eHealth literacy) directly imply the creation of a "digital divide" in urgent care access. This means that while the online platform offers convenience and potential cost savings for digitally literate segments of the population, it simultaneously erects barriers for vulnerable groups, including older adults, those with long-term conditions, individuals of lower socioeconomic status, and certain ethnic minorities, who may lack the necessary eHealth literacy or digital access. This disparity in access directly challenges the NHS's commitment to universal care and suggests that the benefits of the NHS 111 algorithm are not equitably distributed, potentially widening existing health inequalities in the initial point of care access.

Table 2: Summary of Identified Biases and Disparities in NHS 111 Algorithm Outcomes

6. Regulatory Framework and Clinical Governance

NHS 111 Online as a Class 1 Medical Device

NHS 111 Online is formally regulated as a Class 1 medical device under the UK Medical Devices Regulations 2002 (SI 2002 No 618, as amended). In the United Kingdom, all medical devices, including software, are required to be registered with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) before they can be legally placed on the market.

Medical devices are categorized into four classes based on their inherent risk level, ranging from Class I (low risk) to Class III (high risk). This classification dictates the varying levels of evaluation required for regulatory approval. Software that provides information intended for diagnosis, clinical decision-making, or therapeutic purposes can be classified as Class IIa or higher, depending on the potential for serious harm. The classification of NHS 111 Online as a Class 1 medical device signifies a foundational level of regulatory acknowledgment of its role in patient care. However, the inherent "low risk" designation associated with Class 1 devices immediately prompts a critical consideration regarding its adequacy in light of the documented "hundreds of thousands of mis-triaged cases annually" and potential safety concerns, such as instances of under-triage or over-triage. This suggests a potential disconnect or gap between the current regulatory classification and the real-world clinical risks and cascading systemic impacts of the algorithm's performance. It implies that a review of this classification, or at least a deeper understanding of its implications for patient safety and system-wide resource allocation, may be warranted to ensure regulatory alignment with observed clinical realities.

Digital Clinical Safety Assurance Standards (DCB0129 and DCB0160)

To ensure the clinical safety of health IT systems, the NHS has established two critical standards: DCB0129 and DCB0160.

DCB0129 – Clinical Risk Management: its Application in the Manufacture of Health IT Systems: This standard places the responsibility on manufacturers of health IT software to provide robust evidence of the clinical safety of their products. Any healthcare organization planning to implement such a solution is entitled to, and should request, this documentation from the manufacturer.

DCB0160 – Clinical Risk Management: its Application in the Deployment and Use of Health IT Systems:This standard is designed to assist health and care organizations in assuring the clinical safety of the health IT software they deploy and utilize. It outlines the processes and responsibilities for managing clinical risks in the operational environment.

Both DCB0129 and DCB0160 mandate the nomination of a Clinical Safety Officer (CSO). This individual must be a senior clinician, currently registered with a professional body such as the General Medical Council (GMC) or the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), and possess sufficient training in clinical safety and clinical risk management. The CSO is responsible for overseeing clinical risk management activities, which include conducting hazard workshops, evaluating evidence of risk mitigation, ensuring proper documentation of risk management processes, and reviewing or developing key documents such as the clinical safety case report and hazard log.

Digital clinical risk management is a rigorous, methodical, and clearly documented process aimed at ensuring that all clinical risks are assessed and appropriately mitigated. Hazards, defined as potential sources of harm, are systematically identified and documented in a "hazard log," which is a foundational document underpinning the evaluation of a product's clinical safety. The culmination of this analysis is formally presented as the "clinical safety case," a structured argument supported by evidence demonstrating that a system is safe for release. These standards represent a robust framework for managing clinical risk in digital health. The dual responsibility (manufacturer and deployer) and the mandated CSO role aim to ensure safety throughout the IT system lifecycle. The emphasis on continuous monitoring and reporting of safety incidents underscores a proactive approach to risk management, attempting to bridge the gap between regulatory classification and real-world clinical risks by providing detailed processes for safety assurance.

For General Practice, which is increasingly reliant on diverse IT systems, understanding these standards is paramount.Practices must review the manufacturer's DCB0129 assessment and then conduct their own risk assessment using the DCB0160 framework. This ensures that practices comprehend both the digital solution itself and the necessary measures required to operate it safely within their specific organizational context.

International Comparisons and Future Directions

Comparative Analysis of Digital Triage Systems

The UK's NHS 111, powered by NHS Pathways, is part of a growing global trend towards leveraging digital health technologies for urgent care triage. Internationally, comparable digital triage systems exist, offering valuable points of comparison. For instance, NHS 111 has been compared with Healthdirect in Australia, another virtual triage service. Early evaluations suggested that the digital tool used in Australia led to an estimated 33% reduction in predicted call volumes within three years, raising expectations for similar channel shifts in England given increasing internet penetration and smartphone usage.

Across Europe, several countries have invested in digital health and established detailed policies and assessment frameworks for digital health technologies (DHTs), particularly Digital Therapeutics (DTx). Germany, with its Digitale Gesundheitsanwendungen-Verordnung (DiGAV), and the UK, with its Evidence Standards Framework for Digital Health Technologies (ESF), were among the first to introduce specific assessment criteria for DHTs. France has also developed its own DTx assessment framework, Prise en charge anticipée des dispositifs médicaux numériques (PECAN). These frameworks often favor high-level clinical evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses. The Global Digital Health Monitor (GDHM), transitioning to the World Health Organization (WHO), further highlights international efforts to track, monitor, and evaluate the use of digital technology for health across countries, using indicators in areas such as leadership, governance, strategy, and interoperability. This comparative landscape highlights how the UK's approach aligns with global trends in digital health regulation and adoption, while also indicating areas for potential learning and shared challenges in the implementation of AI-driven solutions.

Emerging Technologies and Future Outlook

The NHS is actively exploring the integration of advanced technologies, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), to further transform healthcare delivery and address existing challenges. There is a recognized potential for AI to improve patient outcomes by reducing unnecessary and inefficient care pathways across the world and within various parts of the NHS.

Recent initiatives, such as the Proactive & Accessible Transformation of Healthcare (PATH) initiative, launched by Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust in collaboration with leading AI companies (including Hippocratic AI and Sword Health), exemplify this forward-looking approach. PATH aims to fundamentally rethink patient pathways from referral to recovery, leveraging frontier machine learning and agentic AI technologies. The core vision is to shift healthcare delivery from hospital to community, from analogue to digital, and from treatment to prevention, thereby building a more proactive, coordinated, and efficient health system.

A key aspect of this future vision involves deploying AI agents to support medical staff with patient triage, with the explicit goal of providing clinicians with more time to focus on complex or sensitive cases. This strategic direction aligns with the broader ambition for the NHS to become the most AI-enabled care system in the world, as outlined in the government's 10-Year Health Plan. This emphasis on emerging technologies suggests a recognition of the current system's limitations and a proactive stance on leveraging advanced technology to address them. The focus on AI-driven patient flow optimization and clinician support implies a future where algorithms play an even more central role, necessitating continued vigilance over safety, bias mitigation, and seamless system-wide integration to ensure equitable and effective care.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The NHS 111 service, underpinned by the NHS Pathways algorithm, represents a critical and evolving component of the UK's urgent and emergency care infrastructure. Its strategic intent to standardize triage, streamline patient access, and manage demand across various healthcare settings is clear. The service has successfully established a widely accessible digital and telephone triage system, with the online component demonstrating notable cost-efficiency at the point of contact. Furthermore, the continuous development and clinical oversight of NHS Pathways reflect a robust commitment to adaptive governance and patient safety.

However, the analysis reveals significant complexities and limitations that temper the service's overall effectiveness. Despite its design, NHS 111 has not consistently achieved its primary objective of reducing overall demand on emergency departments and ambulance services. This is largely attributable to persistent challenges such as over-triage, where patients are directed to higher acuity services than necessary, and a substantial rate of patient non-compliance with advice, leading to "rebounding" to emergency care. A critical bottleneck lies in the capacity constraints of primary care services, which struggle to meet the demand generated by NHS 111 referrals, further exacerbating the strain on emergency pathways.

Perhaps most concerning are the documented instances of algorithmic bias and health inequalities. The digital-first approach risks creating a "digital divide," disadvantaging older individuals, those with long-term conditions, and certain ethnic minority groups who may lack eHealth literacy or digital access. Furthermore, biases embedded in the algorithm's design or training data can lead to differential treatment, misdiagnosis, or inappropriate advice based on demographic factors, eroding trust and potentially worsening existing health disparities. While a regulatory framework exists, the classification of NHS 111 Online as a low-risk medical device warrants re-evaluation in light of its real-world clinical impact.

To truly unravel the full potential of the NHS 111 algorithm and ensure it serves all patients equitably and efficiently, a multi-faceted approach is recommended:

Enhance Algorithmic Accuracy and Reduce Over-triage: Continue to rigorously refine NHS Pathways content based on real-world patient outcomes and comprehensive clinical feedback. This should involve ongoing auditing of triage dispositions against actual patient needs upon arrival at downstream services. Furthermore, explore mechanisms to integrate more clinical decision support at the non-clinical call handler level, or expand direct clinical review for complex or ambiguous cases, to reduce the propensity for overly cautious referrals.

Improve Patient Compliance and Trust: Invest in targeted public education campaigns to clearly articulate the purpose and appropriate utilization of NHS 111, as well as the benefits of adhering to its advice. Actively solicit and address patient concerns regarding the relevance of questions asked and the perceived accuracy and appropriateness of the advice given. Building patient trust requires not only accurate triage but also demonstrable, timely access to the recommended downstream services.

Address Health Inequalities and Digital Exclusion: Implement proactive and comprehensive strategies to bridge the digital divide, ensuring equitable access to urgent care advice for all demographic groups. This could involve expanding digital literacy programs, providing assisted digital access points, or maintaining robust non-digital alternatives for those unable to engage online. Critically, rigorously audit the algorithm for biases related to age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Mitigation strategies must include diversifying training data, incorporating social determinants of health into algorithmic logic where appropriate, and ensuring cultural competence in content development.

Strengthen Systemic Capacity and Integration: A fundamental prerequisite for NHS 111's success is addressing the underlying capacity constraints in primary care. This requires strategic investment and workforce planning to ensure that patients referred by NHS 111 can access timely appointments and services. Concurrently, foster deeper integration and interoperability between NHS 111 and all downstream services (GPs, urgent treatment centers, mental health services, community care) to ensure seamless patient flow, reduce fragmentation, and minimize the "rebounding" of patients to A&E.

Evolve Regulatory and Governance Frameworks: Continuously review and adapt regulatory classifications for AI-driven triage systems, such as the Class 1 medical device designation for NHS 111 Online, to ensure they adequately reflect the real-world clinical risks and systemic impacts. Strengthen clinical governance mechanisms, including continuous safety monitoring, robust audit processes, and proactive learning from incidents, with an explicit focus on identifying and rectifying inequities in patient outcomes. This proactive regulatory stance will be crucial as AI becomes more pervasive in healthcare decision-making.

FAQ Section

Q: What is the NHS 111 algorithm? A: The NHS 111 algorithm is a crucial component of the NHS Pathways system, used to assess patients and direct them to appropriate care services.

Q: How does the NHS 111 algorithm work? A: The algorithm assesses patients based on their reported symptoms, providing a structured approach to determining the appropriate level of care needed.

Q: What are the limitations of the NHS 111 algorithm? A: The algorithm's risk-averse design can lead to over-referrals to emergency services, and there are concerns about its lack of clinical validation.

Q: How is the NHS 111 algorithm being improved? A: Ongoing efforts include faster response times and the introduction of AI chatbots to enhance the algorithm's effectiveness and personalization.

Q: What is the impact of the NHS 111 algorithm on healthcare services? A: The algorithm helps manage the demand on emergency services while ensuring that patients receive the care they need.

Q: How does the NHS 111 algorithm assess patients? A: Patients interact with the algorithm by answering a series of questions about their symptoms, and the algorithm determines the next steps based on their responses.

Q: What are the concerns about the NHS 111 algorithm? A: There are concerns about the algorithm's lack of clinical validation and the limited clinical input in many calls, which can affect the accuracy of the triage process.

Q: What role does clinical input play in the NHS 111 algorithm? A: Clinical input is crucial for improving the accuracy of the triage process and providing more efficient care pathways.

Q: How does the NHS 111 algorithm ensure patient safety? A: The algorithm is designed to be risk-averse, often recommending higher levels of care to ensure that patients receive the help they need.

Q: What future directions are being considered for the NHS 111 algorithm? A: Future directions include the integration of advanced technologies and improvements to the overall NHS 111 service to enhance the algorithm's effectiveness.