Understanding the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS)

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) is a cornerstone of emergency medical care in Canada, functioning as a standardized five-level system utilized in emergency departments (EDs) and urgent care (UC) facilities to assess patients based on the urgency of their condition. Its primary purpose is to provide a systematic and standardized approach to triage, enabling healthcare professionals, typically triage nurses, to rapidly determine the acuity of a patient's condition and prioritize their care accordingly. This ensures that individuals with the most critical, life- or limb-threatening conditions receive prompt medical attention, while also attending to those with less urgent needs in a timely manner.

The application of CTAS occurs at the initial point of patient contact with the ED. The triage assessment considers a variety of factors, including the patient's chief complaint, vital signs, relevant clinical information, and specific objective modifiers. The widespread adoption of CTAS across Canada underscores its importance in enhancing consistency and fairness in patient assessment and prioritization, thereby improving patient flow within busy emergency departments and contributing to better overall patient outcomes. Beyond its immediate clinical utility in prioritizing individual patients, the standardization brought by CTAS facilitates more effective communication among healthcare providers. A common language of acuity allows for clearer understanding of patient status during handovers, consultations, and when coordinating care across different units or facilities. This shared understanding is crucial in complex, fast-paced emergency environments.

2. Historical Development and Governance of CTAS

The genesis of the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale dates back to 1995, when Dr. Robert Beveridge adapted a triage scale developed by an Australian National Triage Scale group for the Canadian healthcare context. This initiative garnered significant national interest, leading to the formation of the CTAS National Working Group (CTAS NWG). This collaborative body comprised representatives from key national organizations, including the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP), the National Emergency Nurses Affiliation (NENA), l'Association des médecins d'urgence du Québec (AMUQ), the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS), and the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada (SRPC). The involvement of such a diverse group of stakeholders from the outset was instrumental in ensuring that the scale would be robust, widely applicable, and address the varied needs of emergency care providers across different specialties and settings. This collaborative approach fostered buy-in and facilitated the national adoption of the scale.

A series of consensus meetings culminated in the endorsement of CTAS as the national standard in May 1998, with the formal "Implementation Guidelines" published in October 1999. The development of CTAS has been an iterative process, marked by several key milestones reflecting its evolution and refinement. Recognizing the unique needs of younger patients, the "Paediatric CTAS Implementation Guidelines" were published in 2001, a result of the joint efforts of the CTAS NWG and the CPS. A significant step towards data standardization occurred with the publication of the Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) National Presenting Complaint List in 2003. This list, comprising 161 complaints, was subsequently integrated into the "Revised Adult CTAS Guidelines" in 2004, which also clarified the application of acuity modifiers for each complaint. Further updates to the CEDIS Presenting Complaint List, Adult CTAS Guidelines, and Paediatric CTAS Guidelines, along with revisions to all CTAS educational materials, were undertaken in 2008.

The governance of CTAS continues to involve key organizations such as CAEP, which was founded in 1978 and plays a leading role in advancing excellence in emergency medicine across Canada. The CTAS NWG remains central to the ongoing review and revision of the guidelines. This continuous process of refinement, driven by research, practical experience, and evolving healthcare needs, underscores that CTAS is not a static tool but rather a dynamic system designed to adapt to new evidence and challenges in emergency care. This commitment to iterative improvement ensures its continued relevance and effectiveness.

3. The CTAS Framework: Levels, Complaints, and Modifiers

The CTAS framework is built upon a five-level acuity scale, a standardized list of presenting complaints, and a system of modifiers that refine triage decisions. This structured approach aims to ensure consistency and accuracy in patient prioritization.

3.1. The Five CTAS Levels and Definitions

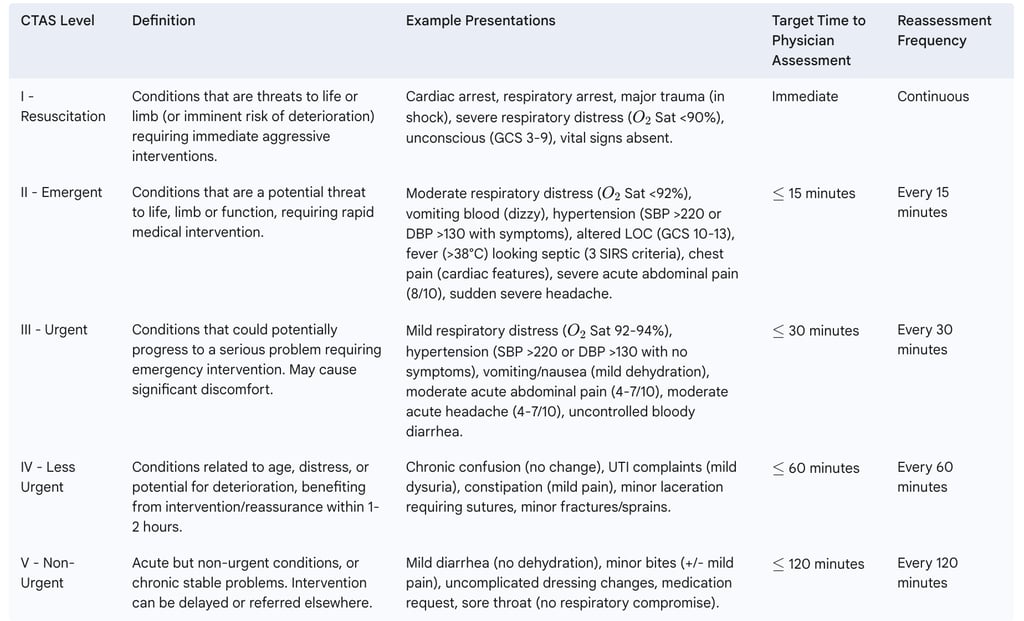

CTAS categorizes patients into five distinct levels, each signifying a different degree of urgency and dictating the expected timeliness of medical intervention. These levels are universally applied and form the core of the triage decision.

Level I - Resuscitation: These patients present with conditions that are an immediate threat to life or limb, or are at imminent risk of deterioration, requiring immediate aggressive interventions. Examples include cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest, major trauma with shock, severe respiratory distress (e.g., oxygen saturation (O2 Sat) <90%), and unconsciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 3-9).

Level II - Emergent: This level includes patients with conditions that pose a potential threat to life, limb, or function, necessitating rapid medical intervention or delegated acts. Examples are moderate respiratory distress (O2 Sat <92%), vomiting blood with dizziness, severe acute pain (e.g., 8/10 on a pain scale), suspected stroke with symptom onset < 4.5 hours, chest pain with cardiac features, altered level of consciousness (GCS 10-13), or fever (>38°C) in an immunocompromised patient or one appearing septic.

Level III - Urgent: Patients at this level have conditions that could potentially progress to a serious problem requiring emergency intervention. These conditions may be associated with significant discomfort or affect the patient's ability to perform daily activities. Examples include mild respiratory distress (O2 Sat 92-94%), moderate acute abdominal or head pain (4-7/10), hypertension (Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) >220 mmHg or Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP) >130 mmHg) without acute symptoms, or mild dehydration.

Level IV - Less Urgent: These patients present with conditions related to their age, distress, or potential for deterioration or complications that would benefit from intervention or reassurance, typically within 1-2 hours. Examples include minor fractures or sprains, earaches, chronic back pain, uncomplicated lacerations requiring sutures, or urinary tract infection symptoms with mild dysuria.

Level V - Non-Urgent: This level encompasses patients with minor acute conditions or stable chronic conditions. Investigation or interventions for these issues could be delayed or referred to other healthcare settings. Examples include minor lacerations not requiring closure, mild abdominal pain, requests for dressing changes or medication refills, or mild diarrhea without dehydration.

Table 1 provides a summary of these levels.

Table 1: CTAS Levels, Definitions, and Example Presentations

3.2. The Triage Process and Role of Presenting Complaints (CEDIS)

The triage process in the ED is a systematic sequence of actions designed to rapidly assess and categorize patients. It typically begins with a "Critical Look" or "First Look"—a rapid visual assessment to identify patients in immediate distress, such as those in respiratory or cardiac arrest, severe respiratory distress, shock, or unconsciousness, who require immediate movement to a resuscitation area. For unstable patients, triage may be performed at the bedside. Infection control measures are also assessed early to identify risks of communicable diseases.

A crucial step is identifying the patient's presenting complaint, or chief complaint. For this, CTAS utilizes the Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List. CEDIS is a standardized list endorsed by major Canadian emergency medicine organizations, featuring 17 categories and 167 distinct complaints. Its purpose is to facilitate the development of a comprehensive national ED dataset for comparisons, quality improvement, and research. If a patient presents with multiple complaints, the triage nurse selects the one that enables assignment to the highest appropriate acuity level. The presenting complaint is the primary determinant of the CTAS acuity level, which can then be modified by first- and second-order modifiers. This structured approach, integrating a standardized complaint list with a flexible system of modifiers, allows for both consistency in data capture and nuanced clinical decision-making tailored to individual patient presentations.

3.3. Understanding First-Order Modifiers

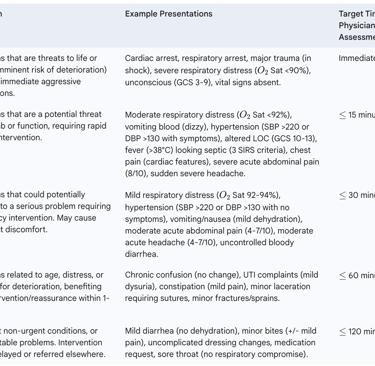

First-order modifiers are general physiological indicators or critical historical factors that are applied after the presenting complaint has been determined. They can elevate the assigned CTAS level based on objective measures of physiological derangement or high-risk features. These modifiers act as crucial safety nets, ensuring that patients whose initial presenting complaint might suggest a lower acuity are appropriately upgraded if their vital signs or other key indicators point to a more serious condition. This mechanism is vital for preventing under-triage of patients who may appear deceptively stable.

The main categories of first-order modifiers include:

Vital Signs:

Respiratory Distress: Assessed based on respiratory effort, ability to speak, oxygen saturation, and presence of stridor or cyanosis. It is graded as Severe, Moderate, or Mild.

Severe distress (e.g., O2 Sat <90%, single-word speech, cyanosis, lethargy) typically warrants CTAS Level 1.

Moderate distress (e.g., O2 Sat <92%, speaking in phrases, increased work of breathing) typically warrants CTAS Level 2.

Mild distress (e.g., O2 Sat 92-94%, shortness of breath on exertion, able to speak in sentences) typically warrants CTAS Level 3.

Hemodynamic Status: Evaluated based on signs of perfusion, heart rate, and blood pressure.

Shock (e.g., severe end-organ hypoperfusion, hypotension, significant tachycardia/bradycardia, decreased LOC) indicates CTAS Level 1.

Hemodynamic compromise (e.g., borderline perfusion, unexplained tachycardia, postural hypotension) suggests CTAS Level 2.

Vital signs at the upper/lower ends of normal, especially if differing from the patient's baseline and related to the complaint, may indicate CTAS Level 3. Normal vital signs are typically associated with CTAS Levels 4 or 5.

Level of Consciousness (LOC): Assessed using general responsiveness and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

Unconscious (GCS 3-9, unable to protect airway, continuous seizure) is CTAS Level 1.

Altered LOC (GCS 10-13, new confusion/agitation, disorientation) is CTAS Level 2.

Normal LOC (GCS 14-15) allows for CTAS Levels 3, 4, or 5 based on other factors.

Temperature: Fever (typically >38°C or >38.5°C depending on specific guidelines) is considered, especially in conjunction with immune status or signs of sepsis.

Immunocompromised patients with fever, or those appearing septic (e.g., 3 positive Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria), are often triaged to CTAS Level 2. SIRS criteria include temperature >38°C or <36°C, heart rate >90 bpm, respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 <32 torr, and WBC >12,000 cells/mm³, <4,000 cells/mm³ or >10% band forms.

Patients who look unwell with fever and 1 or 2 SIRS criteria may be CTAS Level 3, while those who look well with fever as the only SIRS criterion may be CTAS Level 4.

Pain Score: Pain is assessed for severity (e.g., 0-10 scale), location (central vs. peripheral), and character (acute vs. chronic).

Severe acute central pain (e.g., 8-10/10) typically warrants CTAS Level 2.

Severe acute peripheral pain or severe chronic central pain often results in CTAS Level 3.

Moderate acute central pain (4-7/10) is typically CTAS Level 3.

The subjective nature of pain and its interpretation by both patient and nurse introduces complexity. While scales provide a number, the clinical context, patient's history, and non-verbal cues are critical. Over-reliance on a score without considering these factors can lead to mis-triage. The distinction between central (potentially life/limb-threatening) and peripheral pain, and acute versus chronic pain, attempts to add objectivity, but these distinctions themselves require careful clinical judgment.

Bleeding Disorder: Patients with known bleeding disorders (e.g., hemophilia, on anticoagulants) or signs of significant, uncontrolled bleeding are upgraded, often to CTAS Level 2 if the bleed is life- or limb-threatening (e.g., intracranial, massive gastrointestinal) or CTAS Level 3 for moderate/minor bleeds (e.g., epistaxis, hemarthrosis).

Mechanism of Injury (MOI): A high-risk MOI (e.g., pedestrian struck by vehicle, fall from significant height, penetrating injury to high-risk areas) can elevate a trauma patient to CTAS Level 2, even if initial vital signs are stable, due to the potential for occult injuries.

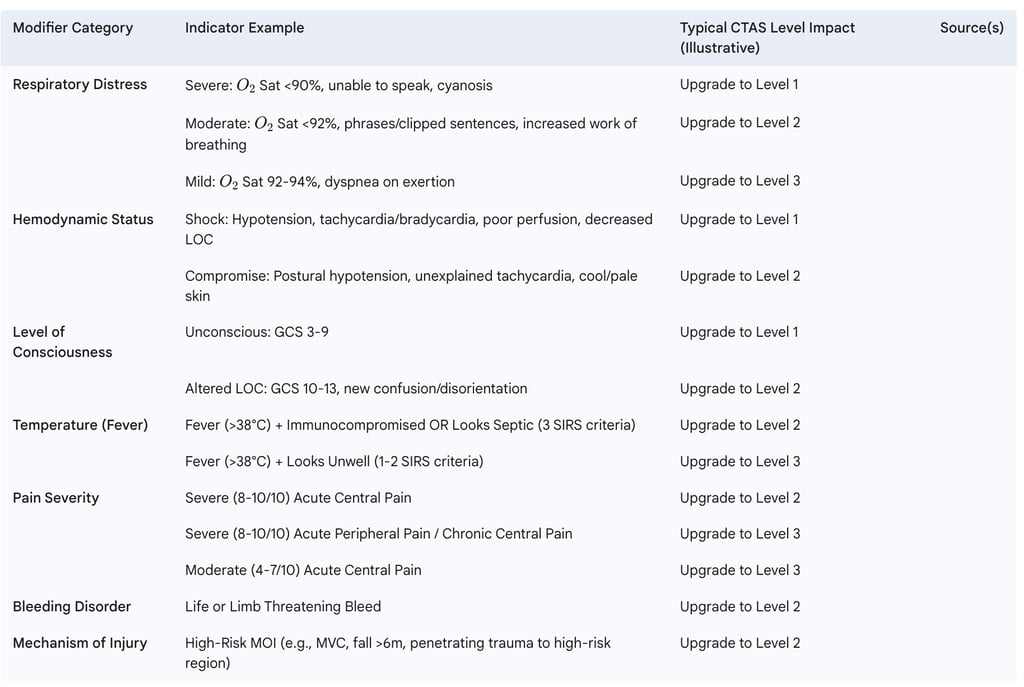

Table 2 summarizes key first-order modifiers.

Table 2: Key First-Order Modifiers and Their Impact on CTAS Level

3.4. Understanding Second-Order Modifiers

Second-order modifiers are applied after the presenting complaint and first-order modifiers have been considered. They are typically more complaint-specific and address situations where first-order modifiers alone may be insufficient or less relevant for accurately determining acuity. An important principle is that second-order modifiers should not be used to downgrade a CTAS level if a higher level is already indicated by the presenting complaint or a first-order modifier. The use of these modifiers, particularly in electronic CTAS (eCTAS) systems with computer-based prompts, has been associated with increased triage consistency, especially for non-specific complaints.

Second-order modifiers can be broadly categorized:

Supplements to first-order modifiers: These apply to multiple presenting complaints and provide further refinement. Examples include:

Blood Glucose Level: For patients presenting with altered LOC, confusion, hyperglycemia, or hypoglycemia. A blood glucose <3 mmol/L with symptoms (confusion, diaphoresis, seizure) typically warrants CTAS Level 2, while <3 mmol/L without symptoms may be Level 3. Conversely, glucose >18 mmol/L with symptoms (dyspnea, dehydration) can be Level 2, versus Level 3 if asymptomatic.

Degree of Dehydration: Assessed in patients with vomiting, diarrhea, or general weakness. Severe dehydration with shock signs is CTAS Level 1. Moderate dehydration (dry mucous membranes, tachycardia) is CTAS Level 2. Mild dehydration (thirst, concentrated urine, stable vitals) is CTAS Level 3. Potential dehydration (ongoing fluid loss but no current symptoms) may be CTAS Level 4.

Hypertension (Adults): For patients with elevated blood pressure. SBP >220 mmHg or DBP >130 mmHg with any other symptoms (e.g., headache, chest pain, neurological deficit) is CTAS Level 2. The same readings without other symptoms may be CTAS Level 3. Lower, yet still significantly elevated, pressures with symptoms may be Level 3, and without symptoms, Level 4 or 5.

Presenting complaint-specific modifiers: These are tailored to particular complaints where general physiological markers may not fully capture the risk. Examples include :

Obstetrics: For pregnancies $\geq$20 weeks gestation.

Mental Health: Considerations for suicidal ideation/plan, homicidal behavior, severe agitation, or risk of harm to self/others. For instance, active suicidal intent with a clear plan, or violent/homicidal behavior, is often CTAS Level 2.

Chest pain, non-cardiac features: "Other significant chest pain (ripping or tearing)" suggests CTAS Level 2.

Extremity weakness / symptoms of CVA: Time of symptom onset is critical; <4.5 hours often warrants CTAS Level 2, while >4.5 hours or resolved symptoms may be Level 3.

Difficulty swallowing / dysphagia: Presence of drooling or stridor elevates to CTAS Level 2; possible foreign body may be Level 3.

The interaction between the CEDIS presenting complaint list and the structured application of first- and then second-order modifiers creates a decision-making pathway that is both standardized and capable of responding to nuanced clinical presentations. This hierarchical application ensures that the most life-threatening conditions identified by vital signs or critical modifiers take precedence, while still allowing for specific complaint characteristics to influence the final triage level.

3.5. Patient Reassessment Protocols

Patient reassessment is a critical component of the triage process, acknowledging that a patient's condition can change, potentially deteriorate, while they are waiting for physician assessment or treatment in the ED. The CTAS guidelines stipulate specific minimum frequencies for reassessment based on the initial triage level assigned. These are:

CTAS Level I: Continuous nursing care/monitoring.

CTAS Level II: Every 15 minutes.

CTAS Level III: Every 30 minutes.

CTAS Level IV: Every 60 minutes.

CTAS Level V: Every 120 minutes.

The extent of reassessment depends on the patient's presenting complaint, their initial triage level, and any changes they report or that are observed by nursing staff. It is also standard practice to advise patients to return to the triage desk if they feel their condition is worsening. Any changes in patient acuity identified during reassessment should be documented; however, the original CTAS level assigned at the initial triage encounter is generally not changed. Instead, documentation reflects the evolving clinical picture and any interventions initiated. This dynamic process of ongoing surveillance and reassessment is a key patient safety feature within the CTAS framework, ensuring that patients who become more unwell while waiting can be identified and their priority for care adjusted accordingly.

4. Application of CTAS in Specific Contexts and Populations

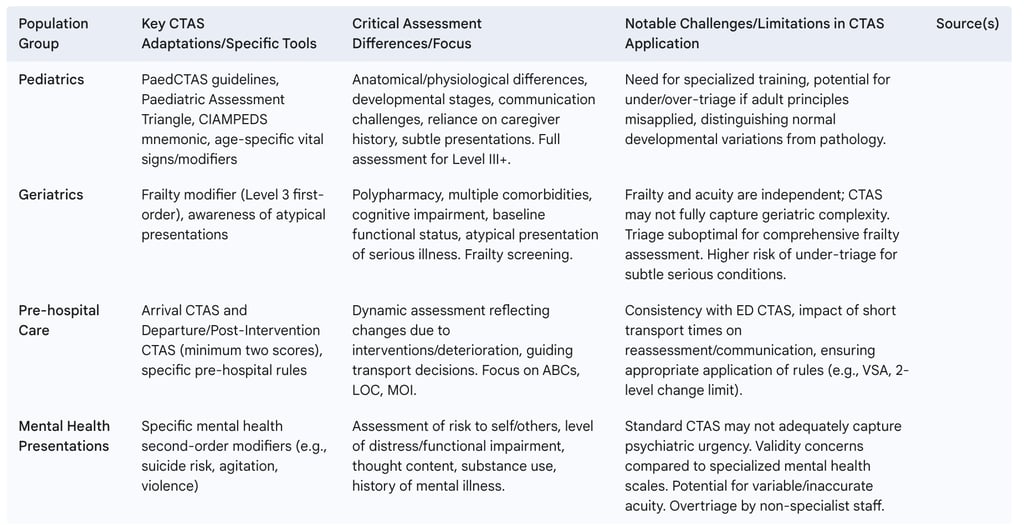

While CTAS provides a universal framework, its application requires adaptation and specific considerations for diverse patient populations and unique care settings. These tailored approaches aim to maintain the validity and reliability of triage across the spectrum of emergency presentations.

4.1. Paediatric CTAS (PaedCTAS)

Recognizing that children are not simply small adults, specific Paediatric CTAS (PaedCTAS) guidelines were developed and published in 2001, with subsequent revisions, for example, in 2008. The core five CTAS levels and their definitions remain the same as for adults, as does the fundamental process of using a presenting complaint, assessment, and modifiers. However, key differences exist in assessment techniques, methods of interviewing, and the interpretation of findings due to anatomical, physiological, psychological, and social distinctions in children. For example, children have proportionally larger heads, smaller airways, and age-variable breathing patterns, and their therapy is often weight-dependent.

The PaedCTAS assessment often follows a three-step approach: initial assessment of illness/injury, evaluation of the presenting complaint, and assessment of behavioral and age-related complaints. A "First Look" utilizing the Paediatric Assessment Triangle (Appearance, Work of Breathing, Circulation to Skin) is a rapid initial evaluation tool. While Level I and II patients undergo a quick assessment, a full assessment is recommended for Level III and below to avoid missing subtle presentations in children; CTAS IV and V patients must have normal vital signs for their age.

Specific considerations in paediatric triage include conditions like prematurity, congenital anomalies, metabolic diseases, technology-dependent children, and developmentally challenged children, as well as the possibility of child maltreatment. Common paediatric presentations to the ED include fever, respiratory difficulties, vomiting and/or diarrhea, injuries, and changes in behavior. The CIAMPEDS mnemonic (Chief complaint, Immunization, Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Events surrounding, Diet/Diapers, Symptoms associated) is a tool used to guide history taking in paediatric patients. The complexity arises not just from different physiological norms but also from communication challenges and the need to interpret signs and symptoms in the context of developmental stages. This makes paediatric triage a specialized skill requiring dedicated training and resources.

4.2. Geriatric Considerations and Frailty in CTAS

Elderly patients frequently present to the ED with complex medical histories and atypical manifestations of illness, often resulting in more severe conditions and higher rates of hospital admission compared to younger adults. Studies have shown that CTAS demonstrates high validity in elderly ED patients for categorizing severity and, importantly, for recognizing those who require immediate life-saving interventions. For instance, one study found that for patients aged ≥ 65 years, CTAS scores correlated significantly with severity markers like mortality and ICU admission, and a CTAS score of ≤ 2 had a sensitivity of 97.9% and specificity of 89.2% for identifying patients needing immediate intervention.

Recognizing the unique vulnerabilities of older adults, the 2016 CTAS updates incorporated frailty screening into the triage process. Frailty, a state of increased vulnerability to stressors, can significantly impact outcomes. The frailty modifier in CTAS is a Level 3 first-order modifier designed to help identify frail patients who might present with apparently non-urgent conditions (and would otherwise be assigned CTAS Level 4 or 5) but are at higher risk of deterioration or adverse outcomes if they experience prolonged waits for care.

Interestingly, research examining the relationship between triage acuity (CTAS score) and frailty scores in elderly ED patients (prior to the 2016 updates) found no direct association, suggesting that frailty and acuity are independent yet complementary measures. This finding has significant implications. While CTAS can flag potential frailty, it may not fully capture the complexity of geriatric syndromes. The current frailty modifier serves as an initial screen, but the evidence suggests that a more comprehensive frailty assessment, potentially conducted post-triage, could be more beneficial for identifying at-risk seniors who might benefit from specialized geriatric assessment, interventions, and senior-friendly care pathways. Triage, with its inherent time constraints, may be a suboptimal environment for such a detailed assessment. This points towards a need for a multi-staged approach where initial CTAS can trigger further, more in-depth geriatric evaluation, rather than attempting to condense all risk factors into a single triage score.

4.3. CTAS in Pre-hospital Care

The application of CTAS in the pre-hospital setting by paramedics differs notably from its use within the ED. A key distinction is the requirement for paramedics to apply and document a minimum of two CTAS scores for each patient:

Arrival CTAS: Determined upon reaching the patient, reflecting their condition before paramedic interventions. This score serves as a baseline and is useful for evaluating dispatch procedures and response times relative to patient acuity.

Departure/Post-Intervention CTAS: Determined at the time of leaving the scene or after interventions have been completed. This score helps in deciding the most appropriate receiving facility (e.g., CTAS Level 1 and 2 patients are typically transported to the nearest, most appropriate facility) and reflects any changes in the patient's condition due to pre-hospital care.

Additional CTAS levels may be documented if the patient's condition changes during transport, especially during longer transport times. Specific rules guide pre-hospital CTAS assignment, such as a patient who is vital signs absent (VSA) on arrival and is successfully resuscitated must remain CTAS Level 1. If it's determined on arrival that a patient is "obviously dead," a CTAS score of zero (0) is documented. Another rule stipulates that when considering the patient's response to treatment, subsequent CTAS levels assigned must not be any greater than two levels below the pre-treatment acuity (Arrival CTAS), acknowledging treatment impact while preventing unsafe downgrading.

This dual (or multiple) assessment approach in pre-hospital care makes CTAS not only a tool for standardizing patient handover to the ED but also a dynamic marker of the patient's acuity over time and the impact of paramedic interventions. This provides valuable data for quality assurance and system improvement within emergency medical services. However, ensuring consistency between these pre-hospital CTAS scores and the subsequent CTAS score assigned in the ED can present challenges due to different assessment contexts and the potential for rapid changes in patient status.

4.4. CTAS for Mental Health Presentations

The application of CTAS to patients presenting with mental health crises poses unique challenges, and its validity in this population has been a subject of scrutiny when compared to specialized mental health triage scales. Standard CTAS, with its primary focus on physiological parameters and physical signs and symptoms, may not adequately capture the urgency or risk associated with psychiatric emergencies, which often manifest as disturbances in thought, behavior, or social functioning rather than immediate physiological instability.

Studies have indicated that CTAS acuity assignments for mental health patients can be highly variable and sometimes inaccurate. There are concerns that CTAS may not consistently meet recommended evaluation timeframes for psychiatric patients triaged to urgent levels. For example, one study found that CTAS rated nearly half (48%) of psychiatric patients as urgent and 29% as emergent, but struggled to meet the associated time-to-be-seen targets for these urgent cases. Furthermore, ED nurses using CTAS may tend to overtriage psychiatric patients compared to assessments by psychiatric nurses using more specialized tools.

In contrast, dedicated mental health triage scales, such as the Australian Emergency Mental Health Triage Scale (AEMHTS), have often been found to be more reliable and valid for this population. The AEMHTS, for instance, focuses on assessing danger to self or others and the severity of impairment in social functioning, providing less ambiguous, mental health-specific guidelines. Studies suggest AEMHTS leads to more accurate acuity assignments and better alignment with recommended evaluation times for psychiatric patients.

While CTAS does include some second-order modifiers relevant to mental health presentations—such as for attempted suicide, active suicidal intent with a clear plan, violent or homicidal behavior, or severe anxiety/agitation, which often direct to CTAS Level 2 or 3 —the broader framework may still fall short. Improving education for triage nurses on the specific use of these mental health-related second-order modifiers within CTAS may enhance its reliability and validity for this cohort. However, the fundamental differences in the nature of psychiatric versus physical emergencies suggest that a general acuity scale may always have limitations in this domain.

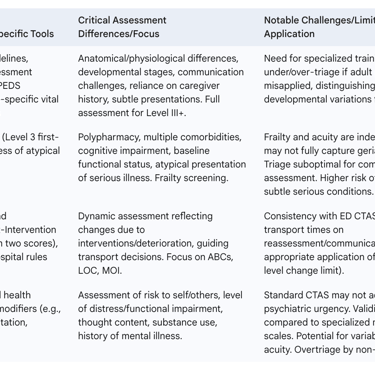

Table 4 summarizes key considerations for these special populations.

Table 4: CTAS Application Considerations for Special Populations

5. Performance Evaluation of CTAS: Reliability, Validity, and Impact

The utility of any clinical tool hinges on its performance. For CTAS, this involves rigorous assessment of its reliability (consistency) and validity (accuracy), as well as its tangible effects on patient care, resource management, and emergency department operations.

5.1. Assessing the Reliability and Validity of CTAS Scores

Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure. In the context of CTAS, this is primarily assessed through:

Interrater Reliability: This measures the degree of agreement between different triage officers when rating the same patient. Multiple studies have reported good to excellent interrater reliability for CTAS, with kappa (κ) statistics often ranging from 0.68 to 0.89. One study found an overall κ of 0.70 for 10 case scenarios among 78 nurses. Interestingly, some research suggests that nurses in community hospitals may exhibit higher agreement than those in teaching hospitals. A critical observation is that the application of newer CTAS revisions, such as the 2008 guidelines, sometimes demonstrated lower reliability initially compared to established prior versions (e.g., 2004 guidelines), with κ values of 0.50 for 2008 revision-dependent scenarios versus 0.73 for 2004-consistent scenarios in one study. This variability, particularly following guideline updates, highlights that CTAS is not a simple "plug-and-play" system. Its reliability is highly sensitive to the quality and consistency of training provided to triage staff and the clarity of the guidelines themselves. Each revision necessitates robust re-education efforts, and the inherent complexity of applying numerous modifiers under pressure means that the "human factor" significantly influences consistency. Ongoing quality assurance, such as regular chart reviews and feedback, is therefore essential for maintaining high reliability.

Intrarater Reliability: This assesses the consistency of a single triage officer when re-rating the same patient on different occasions (or the same scenario at different times). CTAS has generally demonstrated good intrarater reliability, with one study reporting a κ value of 0.74. This suggests that individual nurses, once trained, tend to apply the scale consistently over time.

It is important to note that reliability, while crucial, only speaks to the consistency of the measurement, not necessarily its accuracy or "truthfulness".

Validity refers to the extent to which a tool measures what it is intended to measure – in this case, patient acuity and urgency.

CTAS validity studies have indicated that it can be effectively used as a measure of ED resource needs. There is a demonstrable correlation between ascending CTAS acuity levels and increased resource utilization (e.g., diagnostic tests, consultations, admission).

The scale has shown moderate to strong predictive validity for forecasting resource use.

CTAS scores also correlate significantly with critical patient outcomes such as hospital admission and mortality.

For specific populations, such as elderly patients, CTAS has demonstrated high validity in categorizing severity and identifying the need for immediate life-saving interventions.

However, validating triage scales presents inherent challenges. Defining "true acuity" at a single point in time is difficult, as patient conditions are dynamic and outcomes are confounded by numerous post-triage factors, including the timeliness and effectiveness of care received.

5.2. Effectiveness of CTAS on Patient Outcomes, Resource Utilization, and ED Flow

The implementation of CTAS has been associated with several positive impacts on ED operations and patient care:

Patient Outcomes: Studies have linked CTAS implementation to reduced waiting times for physician assessment, improved patient satisfaction, and decreased overall length of stay in the ED. However, the accuracy of triage is paramount; under-triage, where high-acuity patients are misclassified into lower urgency categories, is associated with significant delays in care and can lead to worsened patient outcomes. This finding underscores a critical patient safety dimension of CTAS. While over-triage might strain resources, under-triage poses a direct threat to patient well-being. Therefore, quality improvement initiatives for CTAS must prioritize strategies to minimize under-triage, such as targeted education on subtle signs in high-risk groups or refinement of specific modifiers. The report in some literature that up to 40% of patients might be mis-triaged is a significant concern warranting continuous attention.

Resource Utilization: CTAS effectively categorizes patients by their anticipated resource needs, aiding in the allocation of staff, beds, and diagnostic services. One study in the UAE found CTAS-based categorization of patients and their subsequent resource allocation to be more accurate than the standard, non-CTAS triage previously in use. The strong correlation between CTAS levels and resource consumption makes it not just a clinical prioritization tool, but also a critical instrument for hospital administration in capacity planning, staffing decisions, and financial forecasting. This dual role means that CTAS data offer value extending beyond the immediate clinical encounter, informing strategic decisions about ED design, budget allocation, and even advocacy for additional resources if trends indicate a consistent rise in high-acuity presentations. However, this also implies that inaccuracies in CTAS application can have cascading effects on these broader administrative and financial considerations.

ED Flow: A primary goal of CTAS is to optimize patient flow through the ED, particularly in high-volume or overcrowded environments. A systematic triage system is vital for managing large patient numbers. High compliance with CTAS-defined "time to be seen by physician" metrics is indicative of the system's efficacy in expediting patient assessment and management, which can lead to higher patient turnover and smoother departmental flow. The advent of electronic CTAS (eCTAS) systems, often with built-in decision support, can further enhance accuracy and help organize patient flow. Factors such as nurses' perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness of the system, quality of training, and years of experience significantly influence the adoption and effective use of eCTAS.

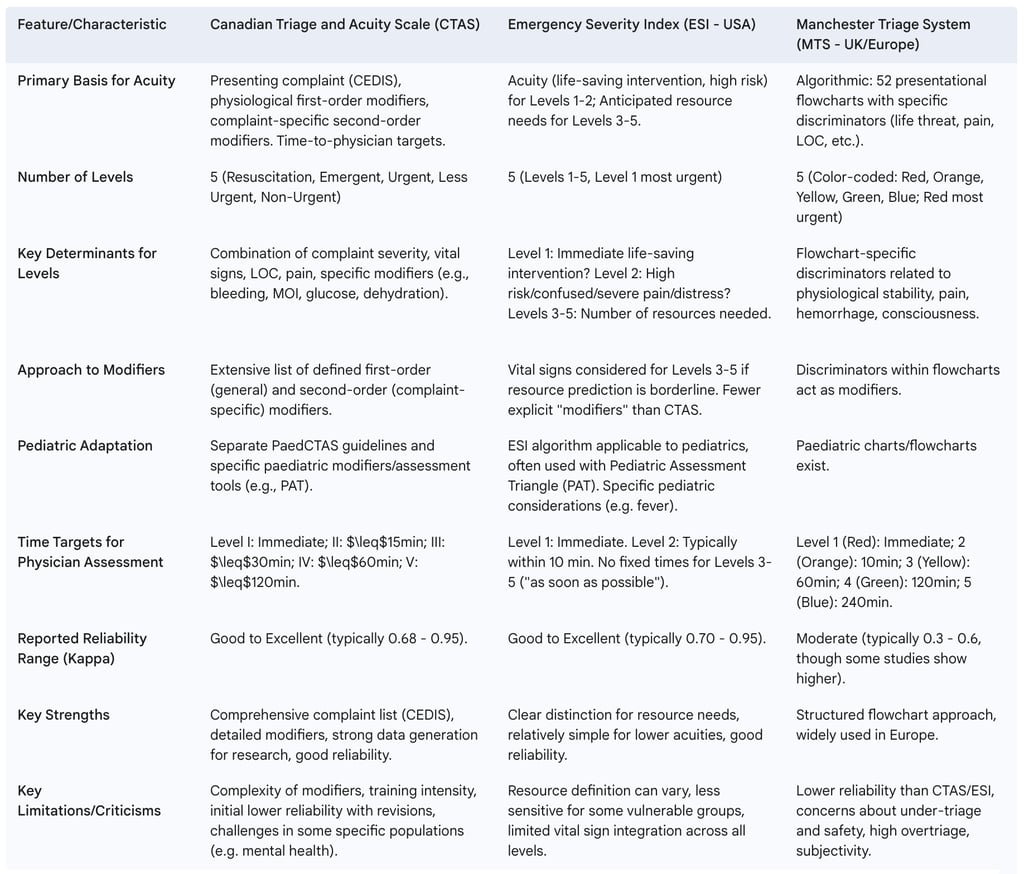

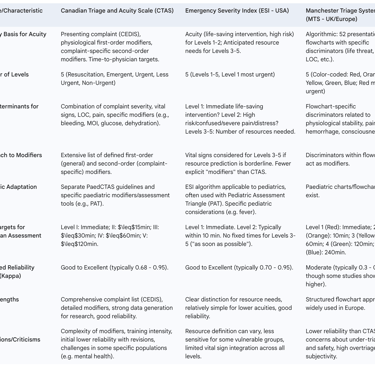

6. CTAS in the International Landscape: A Comparative Perspective

CTAS is one of several five-level triage systems used internationally. Comparing it with other prominent scales, such as the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) used primarily in the USA, and the Manchester Triage System (MTS) common in the UK and parts of Europe, provides valuable context on different approaches to emergency patient prioritization.

6.1. Comparison with Emergency Severity Index (ESI - USA)

The ESI is a five-level ED triage algorithm that categorizes patients based on both acuity and anticipated resource needs. For ESI, Levels 1 (most urgent) and 2 are determined by patient acuity, assessing for immediate life-saving interventions or high-risk situations. Levels 3, 4, and 5, however, are primarily differentiated by the number of resources anticipated for the patient's workup and treatment. A "resource" in ESI has a specific definition, including items like laboratory tests, diagnostic imaging (X-rays, CT scans), IV fluids or medications, and complex procedures like suturing, but excluding oral medications, crutches, or simple wound care.

A key difference from CTAS lies in this resource-based determination for lower acuity levels. CTAS, in contrast, maintains a focus on presenting symptoms, physiological modifiers, and diagnoses (via CEDIS) to determine how long a patient can safely wait for assessment across all five levels. ESI does not employ an extensive list of diagnoses or symptoms in the way CTAS integrates with CEDIS. Furthermore, ESI does not set fixed time limits for physician assessment for its Levels 3 to 5, unlike CTAS which has defined targets for all levels. This fundamental divergence in categorizing less urgent patients reflects differing philosophies on the primary role of ED triage for this cohort: ESI appears to lean towards predicting resource consumption, potentially for system planning and fast-track streaming, while CTAS maintains a consistent focus on clinical risk and timeliness of assessment. This could lead to different patient pathways and operational emphases in EDs using ESI versus CTAS.

In terms of performance, both CTAS and ESI generally report good to very good reliability, with kappa statistics often in the 0.7 to 0.95 range, and both are extensively studied. However, ESI has its own limitations, including inconsistent inter-rater reliability (particularly for ESI Levels 2 and 3), potentially inadequate sensitivity for certain vulnerable populations like elderly or psychiatric patients, limited direct incorporation of vital signs into all decision points, and a lack of formalized dynamic reassessment protocols within its core algorithm. Like CTAS, ESI can also result in under-triage or over-triage, and demographic disparities in triage accuracy have been reported.

6.2. Comparison with Manchester Triage System (MTS - UK/Europe)

The MTS employs a distinct, algorithmic approach using 52 presentational flowcharts, each corresponding to a chief complaint (e.g., "headache," "abdominal pain"). Within each flowchart, a series of questions related to specific discriminators (e.g., life threat, pain level, hemorrhage, level of consciousness, temperature) guides the triage nurse to one of five color-coded urgency levels.

This flowchart-driven methodology differs significantly from CTAS, which uses a broad presenting complaint list (CEDIS) and then applies a more flexible set of general and complaint-specific first- and second-order modifiers. The MTS pain scale is also simpler (typically 3 items) compared to the 10-point scale often used with CTAS. Time limits for physician contact also vary; for example, MTS Level V (non-urgent) suggests a 240-minute target, whereas CTAS Level V is 120 minutes.

Reported reliability for the MTS is often moderate, with kappa statistics generally ranging from 0.3 to 0.6, which is typically lower than those reported for CTAS and ESI. Criticisms of the MTS include concerns about its safety due to potentially high rates of under-triage and low sensitivity in identifying patients at higher urgency levels. Conversely, high rates of over-triage have also been noted, which can lead to inefficient resource utilization. Variability in inter-rater agreement and a significant reliance on nurse expertise, leading to subjectivity, are other cited limitations. The structured nature of MTS flowcharts, while aiming for consistency, might be too rigid or its discriminators not sufficiently robust for all clinical scenarios, potentially leading to errors if patients do not fit neatly into predefined pathways. This contrasts with the more adaptable, modifier-based approach of CTAS. Additionally, similar to other systems, MTS has been criticized for infrequent substantial updates despite evolving medical evidence.

6.3. General Points on Five-Level Triage Systems

Internationally, five-level triage systems like CTAS, ESI, MTS, and the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) are widely accepted as superior to older three- or four-level systems in terms of both validity and reliability. The overarching goal of these systems is to improve patient safety by ensuring timely care for the most urgent cases, and to optimize ED processes by reducing time to treatment, overall length of stay, and resource utilization.

Despite their advantages, all five-level systems face common challenges. One of the most significant is the difficulty in objectively validating "true acuity" at the point of triage, as patient conditions are dynamic and myriad post-triage factors (e.g., quality of care, patient response) confound outcomes used as validation metrics (like admission rates or mortality). This means that no triage system can be a perfect predictor, and all are essentially sophisticated estimation tools rather than definitive diagnostic labels of "true" urgency at a specific moment. Their validity is often judged against proxy measures, which are imperfect reflections of initial acuity. Consequently, the performance of any triage system can vary depending on the specific context, patient population (e.g., age, race), and the presenting complaint. Triaging elderly patients, for example, is a widely recognized difficulty across various systems due to atypical presentations and comorbidities. This inherent limitation underscores the importance of continuous quality improvement, robust training, ongoing research into better validation methods or complementary decision-support tools, and critically, the dynamic process of patient reassessment, as the initial triage score is merely one snapshot in a patient's evolving clinical course.

Table 5 provides a comparative overview of these international systems.

Table 5: Comparative Overview of Major International Five-Level Triage Systems

7. Navigating Challenges: CTAS Implementation, Limitations, and ED Overcrowding

Despite its strengths and widespread adoption, the CTAS framework is not without its challenges. Effective implementation faces hurdles, certain limitations are recognized, and its operation is significantly impacted by the pervasive issue of emergency department overcrowding.

7.1. Implementation Hurdles and Criticisms of the CTAS Framework

Several practical difficulties and criticisms have emerged concerning CTAS implementation and ongoing use:

Training and Education: Adequate training is paramount for consistent and accurate CTAS application. However, some rural institutions have reportedly provided insufficient training for nursing staff. Even when training is available, releasing staff for traditional workshops can be managerially challenging, and while online learning offers convenience, it can present a steep technology learning curve for some nurses and requires dedicated time that may be difficult to find amidst work demands. Experienced ED nurses sometimes express a desire for more advanced or complex case studies in training programs. Furthermore, keeping educational content, especially online modules, current and responsive to learner feedback and guideline updates is an ongoing task. A specific educational focus on the nuanced application of second-order modifiers, particularly for complex presentations like mental health, has been suggested to improve overall reliability and validity.

Rural ED Challenges: The implementation of CTAS in sparsely staffed rural EDs has highlighted particular strains. Physician resources can be severely taxed when attempting to meet CTAS timeframes for physician assessment, especially for non-urgent (CTAS IV and V) cases. This can lead to physician dissatisfaction, friction with nursing staff, and, in some instances, concerns about the potential loss of medical services if physicians leave due to unsustainable on-call burdens. A critical issue has been the misinterpretation or rigid enforcement of CTAS time-to-physician targets by some rural hospital administrators as absolute "standards of care" rather than the "ideals" or "objectives" they were intended to be, often despite a lack of robust evidence supporting specific time-to-physician benchmarks for all CTAS levels. This disconnect between national guideline intent and local administrative enforcement in resource-limited settings points to a failure in communicating the nuances of these objectives or a lack of understanding of how to adapt them appropriately. Adequate registered nurse staffing is also essential for timely triage in these settings.

Reliability of Revisions: While revisions to CTAS aim to improve clarity, objectivity, and standardization , studies have occasionally found that the application of newer revisions (e.g., the 2008 updates) can initially be less reliable than previously established guidelines (e.g., the 2004 version). This counterintuitive finding suggests that increased complexity, even if aimed at greater precision, can temporarily degrade performance as users adapt. It points to a learning curve associated with new guidelines and the potential for new elements to introduce ambiguity or error until they are thoroughly understood and consistently practiced. This underscores the need for robust management of the "implementation dip" with proactive training and support following any guideline revision.

Mental Health Triage: As discussed previously (Section 4.4), the validity and accuracy of standard CTAS for patients with primary psychiatric presentations are areas of concern, with specialized mental health triage scales often performing better for this population.

General Limitations of Five-Level Triage Systems: CTAS, like all five-level triage systems, grapples with the inherent difficulty of definitively validating "true urgency" at a single point in time, as patient conditions are dynamic and outcomes are influenced by many post-triage factors. Performance can also vary by specific clinical context and patient characteristics. The potential for under-triage (missing critically ill patients) or over-triage (overestimating urgency, leading to resource strain) exists, with some literature suggesting that a significant percentage of patients may be mis-triaged overall.

7.2. The Interplay Between CTAS and Emergency Department Overcrowding

ED overcrowding is a critical issue in Canadian healthcare, defined as a situation where the demand for emergency services surpasses the ED's capacity to provide quality care within acceptable timeframes, which are often benchmarked against CTAS targets. It is crucial to understand that ED overcrowding is fundamentally a health system problem, often described as "access block"—the inability to move admitted patients from the ED to appropriate inpatient beds—rather than being solely a consequence of high ED patient volumes or an influx of non-urgent cases.

Overcrowding directly impacts the ability of EDs to meet CTAS time-to-physician targets, particularly for the more urgent CTAS Levels I, II, and III, thereby contributing to a deteriorating standard of care, increased staff burnout, and heightened patient risk. In this challenging environment, CTAS serves as an essential tool to prioritize care and manage the queue of waiting patients. Effective CTAS application can help optimize patient flow and resource utilization, which is especially critical during periods of intense crowding. However, CTAS itself cannot solve the problem of overcrowding; it primarily manages the consequences at the ED's entry point.

The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) and the National Emergency Nurses Affiliation (NENA) have a longstanding position statement on ED overcrowding, identifying it as the most serious issue confronting Canadian EDs. A key assertion in their statement is that "non-urgent" patients (typically CTAS Levels IV and V) do not substantially contribute to ED overcrowding, as they generally consume minimal ED resources, do not occupy acute care stretchers for long periods, and have brief treatment times. This expert position challenges a common public and sometimes policy narrative that blames low-acuity patients for ED congestion. Instead, CAEP and NENA point to systemic causes, including an aging population with more complex needs, shortages of hospital beds and staffing, the impact of Alternate Level of Care (ALC) patients occupying acute inpatient beds due to lack of appropriate community placements, and the consequences of past healthcare restructuring.

Solutions to ED overcrowding, therefore, necessitate system-wide changes. These include improving access to acute inpatient care, ensuring patients are cared for at the appropriate level according to their needs (which means having sufficient community and ALC resources available), and fostering shared responsibility for patient flow across the entire hospital and healthcare system, rather than containing the problem solely within the ED. CTAS data, by clearly illustrating the volume and acuity of patients waiting and the delays they experience, can be a powerful tool for advocating for these broader health system reforms.

8. Ethical Imperatives in CTAS-Guided Triage

The application of CTAS in emergency departments is not merely a technical exercise in categorization; it is deeply intertwined with fundamental ethical principles that govern healthcare. Triage decisions, by their very nature, involve allocating limited resources under pressure, making an ethical framework essential.

8.1. Core Ethical Principles in Triage

Several core ethical principles underpin the practice of triage, and CTAS is designed to help operationalize these in a systematic way :

Beneficence (Doing Good): This principle calls for actions that promote the well-being of patients. In triage, this translates to prioritizing patients based on their medical needs to maximize positive outcomes and ensure that those who are most critically ill receive care first. CTAS, by stratifying patients by urgency, directly serves this principle.

Non-Maleficence (Avoiding Harm): This is the duty to prevent or minimize harm. Triage decisions must carefully weigh the potential benefits of prioritizing one patient against the potential harms of delaying care for another. Accurate CTAS application aims to minimize the harm that could result from delayed assessment and treatment of high-acuity conditions.

Justice (Fairness): This principle demands fair, equitable, and non-discriminatory allocation of healthcare resources based on patients' needs, not on other factors like social status, ability to pay, or personal biases. CTAS provides a standardized, criteria-based framework intended to promote fairness and consistency in these high-stakes decisions. The very existence and use of a standardized system like CTAS can be seen as an ethical response to the challenge of resource allocation, aiming for procedural justice: even if outcomes cannot always be ideal due to systemic constraints, the process of prioritization itself is intended to be as fair and transparent as possible. This can help mitigate moral distress among staff and enhance public trust, provided the system is well understood and correctly applied.

Respect for Autonomy: This involves recognizing a patient's right to make decisions about their own healthcare. While the rapid nature of triage limits extensive shared decision-making, communicating clearly with patients and their families about the triage process, the assigned acuity level, and expected wait times (where feasible) respects their autonomy to some degree.

Utilitarianism: Often, particularly in mass casualty situations or severely overcrowded EDs, a utilitarian approach (seeking the "greatest good for the greatest number") becomes a predominant ethical concept. This may involve making difficult choices where the needs of the many are prioritized, potentially leading to some individuals waiting longer.

8.2. Ethical Challenges in CTAS Application

Despite its aim to systematize ethical decision-making, the application of CTAS faces several ethical challenges:

Resource Scarcity and Overcrowding: Ethical dilemmas are significantly heightened when the demand for emergency services far outstrips available resources. CTAS provides a structured method for making these difficult prioritization decisions, but it does not eliminate the moral distress experienced by healthcare providers who must ration care under such conditions.

Vulnerability: Certain patient populations—such as the elderly, children, individuals with mental health conditions, or those with communication barriers—may be more vulnerable to mis-triage or having their needs inadequately assessed by a general acuity scale. This raises concerns related to justice and equity, as these groups may require more nuanced assessment than the standard CTAS pathway provides. The tension between a utilitarian focus on rapid throughput for the majority and the individualized needs of vulnerable patients is an ongoing ethical challenge. For example, a focus on physiological instability might inadvertently lead to less attention for a frail elderly patient with subtle signs of serious illness or someone experiencing a complex mental health crisis whose primary risk is not physiological. The development of specific considerations within CTAS, like frailty screening or mental health modifiers, reflects an attempt to address this, but it highlights the need for triage nurses to be skilled not only in rule application but also in ethical reasoning and patient advocacy.

Subjectivity versus Objectivity: While CTAS strives for objectivity through defined presenting complaints, vital sign parameters, and specific modifiers, elements of clinical judgment inevitably remain. This judgment, while essential, can also introduce variability and the potential for unconscious bias. Ensuring consistent, high-quality training and ongoing quality assurance for triage personnel is therefore an ethical imperative to uphold the principle of justice.

Data Privacy and Security: With the increasing use of electronic CTAS (eCTAS) systems, ensuring the privacy and security of sensitive patient health information is a critical ethical and legal responsibility.

The unique dynamics of the emergency field, characterized by urgency, instability, and often incomplete information, make triage decisions inherently complex. A clear ethical framework, supported by tools like CTAS, is essential to guide caregivers in navigating these challenges.

9. Conclusion: Synthesizing the Role and Future of CTAS in Emergency Care

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) stands as a pivotal instrument in Canadian emergency medicine. It provides a standardized, five-level system for assessing patient acuity based on presenting complaints and a structured set of physiological and situational modifiers. Its core function is to ensure that patients receive care in a timely manner corresponding to the urgency of their condition, thereby optimizing patient safety and flow within the demanding environment of emergency departments and urgent care centers.

Key Strengths of CTAS include the standardization it brings to triage practice across diverse settings, which enhances communication among healthcare professionals and facilitates more equitable care. By prioritizing the sickest patients, it directly contributes to improved patient safety. The systematic collection of data through CTAS and the associated Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) provides a rich resource for research, quality improvement initiatives, and health system planning. Furthermore, CTAS has demonstrated adaptability, with specific guidelines developed for paediatric patients (PaedCTAS), considerations for geriatric patients including frailty screening, and unique application protocols for pre-hospital care.

Despite these strengths, persistent challenges remain. Ensuring consistent and reliable CTAS implementation requires intensive and ongoing training for triage personnel, particularly with each revision of the guidelines. The application of CTAS in specific contexts, such as under-resourced rural settings or for patients with primary mental health presentations, continues to pose difficulties and may require further refinement or complementary tools. Critically, the effectiveness of CTAS in achieving its time-to-physician objectives is significantly hampered by systemic ED overcrowding, an issue rooted in broader health system capacity and patient flow problems that CTAS itself cannot resolve. The need for ongoing validation of the scale, especially as guidelines evolve and healthcare demographics shift, is also paramount.

Looking to the future directions for CTAS, several areas warrant attention. Continued research into the reliability and validity of CTAS, particularly focusing on the impact of new revisions and its performance in diverse clinical settings and patient populations, is essential. Training methodologies should evolve, potentially incorporating more sophisticated simulation exercises and advanced interactive online modules to enhance skill acquisition and maintenance. The greater integration of decision-support tools, such as mature electronic CTAS (eCTAS) platforms and potentially artificial intelligence-assisted triage algorithms, could improve consistency, reduce cognitive load on triage nurses, and perhaps identify subtle patterns of risk earlier. The evolution of CTAS, from its initial adaptation to its current sophisticated form with specialized guidelines and electronic iterations, mirrors a broader trend in medicine towards more data-driven, standardized, and technologically-supported clinical decision-making. This trajectory suggests that future CTAS development will likely involve even deeper integration with health information technology.

Further refinement of CTAS for special populations, including those with complex mental health needs or frail older adults, will be necessary to ensure equitable and effective triage for all patients. However, it is crucial to recognize that the success and limitations of CTAS are inextricably linked to the human element—the skills, training, experience, critical thinking abilities, and even the psychological well-being of the triage nurses who apply it. No matter how refined the tool becomes, the quality of its application depends fundamentally on the user. Therefore, future efforts must focus not only on the scale itself but also on supporting and developing the professionals who use it. This includes investing in high-quality education, fostering supportive work environments that enable critical thinking even under extreme pressure, and addressing issues of moral distress and burnout associated with high-stakes decision-making in overcrowded EDs.

Ultimately, while CTAS is a vital tool for managing patient flow and prioritizing care at the front door of the emergency system, its full potential can only be realized when coupled with systemic efforts to address the underlying causes of ED overcrowding and ensure adequate resources throughout the healthcare continuum. Ongoing ethical reflection on the application of triage principles in an ever-evolving healthcare landscape will also be crucial to guide its responsible and effective use.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS)?

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) is a five-level triage system developed in Canada to help healthcare professionals quickly evaluate and prioritize patients in emergency departments based on the urgency of their conditions. It ranges from Level 1 (Resuscitation - immediate attention) to Level 5 (Non-urgent - care can wait up to 2 hours).

When was CTAS first implemented?

CTAS was first officially implemented in Canada in 1999 after extensive development and testing through the 1990s. It has undergone several revisions since then, with significant updates in 2004, 2008, and more recently to incorporate new clinical evidence and address implementation challenges.

What are the five levels of CTAS?

The five CTAS levels are: Level 1 (Resuscitation) requiring immediate attention, Level 2 (Emergent) requiring physician assessment within 15 minutes, Level 3 (Urgent) requiring assessment within 30 minutes, Level 4 (Less Urgent) with a target time of 60 minutes, and Level 5 (Non-Urgent) with a target time of 120 minutes.

Who performs CTAS assessments in the emergency department?

CTAS assessments are typically performed by specially trained triage nurses who have completed standardized CTAS education programs and have experience in emergency nursing. Most institutions recommend that triage nurses have at least 1-2 years of emergency department experience before assuming the triage role.

How is CTAS different from other triage systems?

CTAS differs from other systems like ESI (Emergency Severity Index) and MTS (Manchester Triage System) in its assessment approach and decision structure. CTAS uses a complaint-oriented approach with specific modifiers for each complaint type, while ESI incorporates predicted resource utilization and MTS uses 52 presenting complaint flowcharts.

How reliable is the CTAS system?

Research has demonstrated that CTAS has good to very good inter-rater reliability, with kappa values typically ranging from 0.7 to 0.9 when implemented with proper training and support. Reliability is highest for well-defined presentations like chest pain and major trauma, and somewhat lower for complex presentations like mental health concerns.

What modifications exist for pediatric patients in CTAS?

The Pediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (PaedCTAS) includes age-specific vital sign parameters, modified clinical modifiers for pediatric-specific risk factors, and special consideration of family assessment of illness severity. For example, fever in infants under three months automatically triggers a minimum Level 3 designation.

Which countries have adopted CTAS beyond Canada?

CTAS has been adopted in several countries worldwide, including Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, parts of Scandinavia, Qatar, Brazil, and various Caribbean nations. Some implement it as a national standard while others use adapted versions tailored to their healthcare systems and resources.

What training is required to use CTAS effectively?

Effective CTAS implementation typically requires an initial 8-16 hour standardized course combining didactic instruction with case-based learning, followed by annual refresher training. Many institutions also implement mentorship programs and regular case review sessions to maintain consistency and competency.

How does CTAS help improve emergency department efficiency?

CTAS improves efficiency by ensuring patients are seen according to clinical need rather than arrival time, appropriately allocating limited resources, standardizing the assessment process, facilitating communication about patient acuity among staff, and providing metrics for departmental performance monitoring and quality improvement initiatives.

Additional Resources

The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) CTAS Resources - Comprehensive collection of official CTAS guidelines, implementation tools, and educational materials.

Bullard MJ, Musgrave E, Warren D, et al. Revisions to the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) Guidelines 2016 - The most recent comprehensive update to the CTAS guidelines with detailed explanations of changes and clinical applications.

Grafstein E, Bullard MJ, Warren D, Unger B. Revision of the Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List Version 1.1 - Essential companion resource to CTAS detailing standardized presenting complaints.

Emergency Nurses Association. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): A Triage Tool for Emergency Department Care - Useful for understanding a major alternative triage system and how it compares to CTAS.

World Health Organization Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) - WHO's approach to triage in resource-limited settings, providing interesting contrast to CTAS.