The Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale (TTAS)

The development of the Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale (TTAS) was a direct result of this international trend, representing a deliberate move by Taiwan's health authorities to replace an underperforming four-level system with a more robust, evidence-based, five-level model to enhance patient safety and operational efficiency in its increasingly busy EDs.

The hospital emergency department (ED) serves as a critical interface within the modern healthcare delivery system, providing essential care for a wide spectrum of patient conditions, from life-threatening emergencies to less urgent medical problems. Globally, EDs are confronting a sustained and significant increase in patient volume, a phenomenon that has led to widespread overcrowding. This state of systemic stress is not merely an issue of inconvenience; it precipitates a cascade of adverse consequences, including compromised patient safety, diminished quality of care, and escalating healthcare costs. In this high-pressure environment, the need for a systematic, reliable, and efficient method of patient prioritization is paramount. This process, known as triage, is the foundational step in managing patient flow and allocating finite medical resources effectively.

Triage is defined as the process of classifying and prioritizing patients upon their arrival at the ED, based on the acuity and urgency of their medical condition, irrespective of their order of arrival. The fundamental goals of ED triage are threefold: to rapidly identify patients with life-threatening conditions who require immediate intervention; to determine the priority of care for all other patients, ensuring that those with more severe conditions are seen before those with less severe ones; and to direct patients to the most appropriate treatment area within the ED. An effective triage system is therefore essential for mitigating the risks associated with ED crowding, improving patient outcomes, and ensuring the judicious use of diagnostic and therapeutic resources.

Evolution of Triage: From Battlefield Principles to Standardized Five-Level Scales

The concept of triage has its origins in military medicine, particularly during periods of mass casualty, where the utilitarian principle of providing the greatest good for the greatest number of individuals necessitated a systematic approach to sorting the wounded. This historical context emphasized not only the severity of an injury but also the resources required for treatment and the likelihood of survival. While the ethical framework has evolved for civilian healthcare, the core principle of prioritization based on urgency remains.

In the latter half of the 20th century, as civilian EDs became more complex and crowded, informal, subjective methods of triage proved inadequate. This led to the development of more structured systems, initially with three or four levels of acuity. However, these less granular systems often struggled to effectively differentiate among the large cohort of patients who were sick but not in immediate danger of death. A common flaw was the clustering of a majority of patients into one or two large, poorly defined "urgent" categories, which limited the system's utility for effective prioritization and resource management.

In response to these limitations, a global consensus began to emerge around the superiority of five-level triage scales. This shift was driven by a growing body of evidence demonstrating that five-level systems provide better discrimination of patient acuity, leading to improved reliability, validity, and a stronger correlation with clinical outcomes and resource needs. The development of the Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale (TTAS) was a direct result of this international trend, representing a deliberate move by Taiwan's health authorities to replace an underperforming four-level system with a more robust, evidence-based, five-level model to enhance patient safety and operational efficiency in its increasingly busy EDs.

Global Context: Key International Triage Systems (CTAS, ESI, MTS, ATS)

The development and implementation of the TTAS did not occur in a vacuum. It is part of a global landscape of standardized five-level triage systems, each with a slightly different philosophical approach but a shared goal of improving patient prioritization. Understanding these systems provides essential context for appreciating the design and function of the TTAS.

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS): As the direct progenitor of the TTAS, the CTAS is arguably the most relevant international model. Implemented in Canada in the late 1990s, it is a comprehensive, complaint-based system that uses a structured list of presenting complaints along with a set of "first-order" and "second-order" clinical modifiers (such as vital signs, level of consciousness, and pain severity) to assign an acuity level from 1 (Resuscitation) to 5 (Non-Urgent). Its structured, content-rich design is conducive to computerization and has been validated as a reliable tool for prioritizing care.

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI): The ESI is the most widely used triage system in the United States. It employs a unique, four-decision-point algorithm that first assesses for physiological instability to identify Level 1 and Level 2 patients. If the patient is stable, the algorithm then shifts to predict the number of resources (e.g., lab tests, imaging, IV medications) the patient is likely to require to determine if they are Level 3 (two or more resources), Level 4 (one resource), or Level 5 (no resources). This dual focus on both acuity and resource utilization distinguishes it from other major systems.

The Manchester Triage System (MTS): Widely used across the United Kingdom and parts of Europe, the MTS is a presentation-based system that utilizes 53 standardized flowcharts or charts. For a given presentation (e.g., "Chest Pain"), the triage nurse asks a series of questions linked to specific clinical indicators called "discriminators." The presence of a high-level discriminator immediately assigns the patient to a higher acuity level. This highly structured, reductive approach is designed to ensure consistency and safety.

The Australasian Triage Scale (ATS): One of the earliest five-level systems, the ATS is used in Australia and New Zealand. It defines five triage categories based on the maximum time within which a patient should receive medical assessment and treatment. The triage decision is guided by a list of clinical descriptors and physiological parameters associated with each triage level.

The international convergence on these five-level models reflects a shared understanding of the complexities of modern emergency medicine. The decision by Taiwan to adapt the CTAS model was therefore a strategic choice to align its national standard with a well-validated, internationally recognized system, thereby leveraging a global body of research and best practices to address the local challenge of ED overcrowding.

Genesis and Implementation of the Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale

The Predecessor: Limitations of the Four-Level Taiwan Triage System (TTS)

From 1999 until 2010, emergency departments in Taiwan's tertiary hospitals utilized the Taiwan Triage System (TTS), a four-level manual triage scale. While an improvement over subjective assessments, the TTS suffered from a critical flaw common to many four-level systems: poor discrimination ability. Validation studies conducted prior to the transition to a five-level scale revealed that the TTS tended to cluster the vast majority of ED patients into its two middle categories. One large study found that 46.1% of patients were assigned to TTS Level 2 and 45.9% to Level 3, leaving only 7.8% in the most critical Level 1 and a negligible 0.2% in the non-urgent Level 4.

This patient distribution pattern demonstrated that the TTS was failing to effectively stratify patients according to the true urgency and severity of their conditions. When a single triage category contains nearly half of the entire ED population, its utility for prioritizing care becomes severely limited. This lack of granularity was a significant operational handicap, particularly in the face of rising patient volumes and ED overcrowding. Direct comparisons with a five-level model showed that the TTS resulted in significant "overtriage"—the assignment of a higher acuity level than clinically warranted—for a substantial portion of patients. This misallocation not only skewed perceptions of the ED's overall patient acuity but also inefficiently directed resources and attention away from potentially more critical cases. The recognized insufficiency of the TTS was the primary catalyst for seeking a more effective, internationally benchmarked solution.

The Catalyst for Change: Adopting an International Standard

Recognizing the limitations of the TTS, Taiwan's health authorities made a strategic decision to transition to a five-level system, aligning with the global trend toward more granular and validated triage scales. Rather than developing a new system from scratch, they chose to adapt the well-established Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS). This decision positioned Taiwan as the first "franchise model country" for the CTAS, a testament to the system's international reputation for reliability and validity.

The process of adoption was methodical and evidence-based. Pilot studies were initiated as early as 2006 to directly compare the performance of the five-level CTAS against the incumbent four-level TTS within the Taiwanese healthcare environment. The results of these studies were decisive. The CTAS demonstrated markedly superior discrimination in patient triage. Furthermore, the acuity levels assigned by CTAS showed a much stronger and more consistent correlation with key clinical and administrative outcomes, including rates of hospitalization, ED length of stay (LOS), and medical resource consumption. This empirical evidence provided a clear justification for replacing the TTS and formed the foundation for the development of a localized version of the CTAS, which would become the Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale.

Development and National Implementation of the Computerized TTAS in 2010

Following the successful validation of the five-level model, the TTAS was formally developed as a modified version of the CTAS, tailored to the specific needs and context of emergency care in Taiwan. A pivotal and defining feature of the TTAS was its implementation from the outset as a national, computerized system. This was not merely a technological upgrade but a core strategic decision aimed at ensuring the successful rollout and sustained reliability of the new, more complex triage standard.

The transition from a relatively simple four-level manual system to a content-rich five-level scale with over 170 chief complaints and multiple clinical modifiers presented a significant challenge for training and consistent application. By embedding the TTAS logic into a computerized decision support system (CDSS), health authorities could enforce standardization across all hospitals, provide real-time guidance to triage nurses, minimize ambiguity in decision-making, and facilitate the collection of high-quality data for auditing and research. This digital-first approach was instrumental in the system's rapid and successful validation, which relied on consistent data from dozens of academic, regional, and district hospitals. The nationwide implementation of the computerized TTAS was completed in 2010, officially replacing the four-level manual TTS and ushering in a new era of standardized, evidence-based triage in Taiwan. The success of this implementation is inextricably linked to the strategic integration of technology, which served to ensure high fidelity, overcome the challenges of human variability, and establish a robust foundation for a safer and more efficient emergency care system.

Architectural Framework and Assessment Methodology of the TTAS

The Five Levels of Acuity: Definitions, Time-to-Physician Targets, and Clinical Implications

The TTAS is structured around five distinct acuity levels, each with a specific name, clinical definition, and a recommended maximum time to physician assessment or reassessment. This framework provides a clear, hierarchical system for prioritizing patients and managing ED workflow.

Level 1: Resuscitation: This is the highest acuity level, reserved for patients with conditions that pose an immediate threat to life or limb and require aggressive, life-saving interventions. This includes patients in cardiac arrest or those with severe trauma, shock, or respiratory failure.

Time to Treatment: Immediately. There is no acceptable waiting time for these patients.

Level 2: Emergent: This level includes patients with conditions that are a potential threat to life, limb, or organ function. While not in immediate arrest, these patients are critically ill and at high risk of deterioration. Examples include patients with chest pain suggestive of cardiac ischemia, major trauma, or altered mental status.

Time to Reassessment/Treatment: Within 10 minutes. These patients require rapid evaluation and intervention to prevent adverse outcomes.

Level 3: Urgent: This level encompasses patients with conditions that could potentially progress to a serious problem if not treated in a timely manner. These patients often present with significant discomfort that affects their ability to function. Examples include patients with moderate abdominal pain, moderate respiratory distress, or fractures.

Time to Reassessment/Treatment: Within 30 minutes.

Level 4: Less Urgent: This level is for patients whose conditions are less acute but still require assessment and treatment to prevent deterioration or to gain recovery. This may include acute episodes of chronic diseases or minor injuries.

Time to Reassessment/Treatment: Within 60 to 120 minutes.

Level 5: Non-Urgent: This is the lowest acuity level, assigned to patients with non-emergency conditions. These presentations may be acute but are not time-sensitive and could often be managed in an outpatient or primary care setting.

Time to Reassessment/Treatment: 120 minutes or more. These patients can safely wait for assessment, or they may be referred to a more appropriate care setting.

This five-level structure allows for a much more nuanced stratification of patients compared to the previous four-level system, enabling ED staff to more effectively allocate their attention and resources.

The Triage Process: A Step-by-Step Deconstruction

The assignment of a TTAS level is not an arbitrary decision but a systematic process guided by the computerized system. The triage nurse follows a structured methodology that combines the patient's stated reason for visit with objective clinical findings to arrive at an accurate acuity rating.

Selection of Chief Complaint

The triage process begins with the nurse selecting the most appropriate chief complaint from a comprehensive, standardized list based on the patient's statement and initial presentation. The TTAS organizes this vast list of potential presentations into three overarching domains to structure the assessment :

Non-Trauma Domain: This is the largest domain, encompassing 13 categories and 125 distinct chief complaints related to medical illnesses, such as cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, and psychiatric disorders.

Trauma Domain: This domain covers injuries, organized into 14 categories with 41 chief complaints, often based on the anatomical region affected.

Environmental Domain: This smaller domain includes 11 chief complaints related to environmental exposures, such as bites, stings, or temperature-related illnesses.

Application of First-Order Modifiers: Vital Signs, Hemodynamics, Consciousness, and Pain Severity

Once a chief complaint is selected, the system prompts the nurse to assess a set of key clinical indicators known as first-order modifiers or primary adjustment variables. These modifiers are broadly applicable to most presentations and are critical for refining the acuity level beyond what the chief complaint alone would suggest. These include:

Respiratory Distress: Evaluating the patient's work of breathing, respiratory rate, and oxygenation status. Signs of severe distress can immediately elevate a patient to a higher acuity level.

Hemodynamics: Assessing circulatory stability, including heart rate, blood pressure, and signs of perfusion. Evidence of shock or hemodynamic compromise is a critical modifier.

Level of Consciousness: Assessing the patient's neurological status, often using a scale like the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Any alteration from a normal level of consciousness is a significant red flag.

Body Temperature: Identifying significant fever or hypothermia, which can indicate serious infection or environmental exposure.

Pain Severity: Quantifying the patient's pain, as severe, uncontrolled pain is considered a high-acuity condition requiring prompt intervention.

Mechanism of Injury: For trauma patients, understanding the forces involved (e.g., high-speed motor vehicle collision, fall from height) is a crucial modifier for predicting the likelihood of severe internal injuries.

Role of Second-Order Modifiers in Refining Acuity

In some cases, the chief complaint and first-order modifiers may not be sufficient to accurately determine the final acuity level. For these situations, the TTAS incorporates a set of second-order modifiers, or secondary adjustment variables. Unlike the universally applied first-order modifiers, these are specific to a limited number of chief complaints and provide additional, context-sensitive clinical information. For example, in a patient with an eye injury (trauma domain), the presence of a "visual disturbance" would be a critical second-order modifier. Similarly, for a patient with a head, neck, or back injury, the presence of a new "neurologic deficit" would significantly increase their assigned acuity level. These modifiers allow for a more precise and clinically nuanced triage decision in complex or specialized presentations.

The Computerized Decision Support System (CDSS): Standardizing Triage Decisions

The entire TTAS process is facilitated and standardized by the national Computerized Decision Support System (CDSS). The CDSS is not an artificial intelligence that makes the decision for the nurse; rather, it is an interactive tool that structures the assessment process. It presents the standardized lists of chief complaints and systematically prompts the nurse to consider and input the relevant first- and second-order modifiers. By ensuring that every triage assessment follows the same logical pathway and considers the same critical clinical variables, the CDSS minimizes subjective variability and promotes a high degree of objectivity and consistency. This technological backbone is fundamental to the TTAS's proven reliability and is a key reason for its successful implementation on a national scale.

Clinical Validation, Reliability, and Performance

The credibility of any triage system rests on empirical evidence of its reliability (the consistency of its measurements) and its validity (the degree to which it accurately measures what it purports to measure—clinical urgency). The TTAS has been subjected to rigorous scientific evaluation since its implementation, establishing it as a robust and effective clinical tool.

Assessing Inter-Rater Reliability: Evidence from Kappa Statistics

A fundamental requirement for a standardized triage scale is that different trained professionals should assign the same acuity level to the same patient with a high degree of consistency. This property, known as inter-rater reliability, ensures that a patient's priority for care does not depend on the specific nurse performing the triage. The primary validation study for the TTAS, a large prospective, multicenter trial involving over 10,000 patients across 33 hospitals, assessed this property using the weighted kappa statistic, a measure of agreement that corrects for chance.

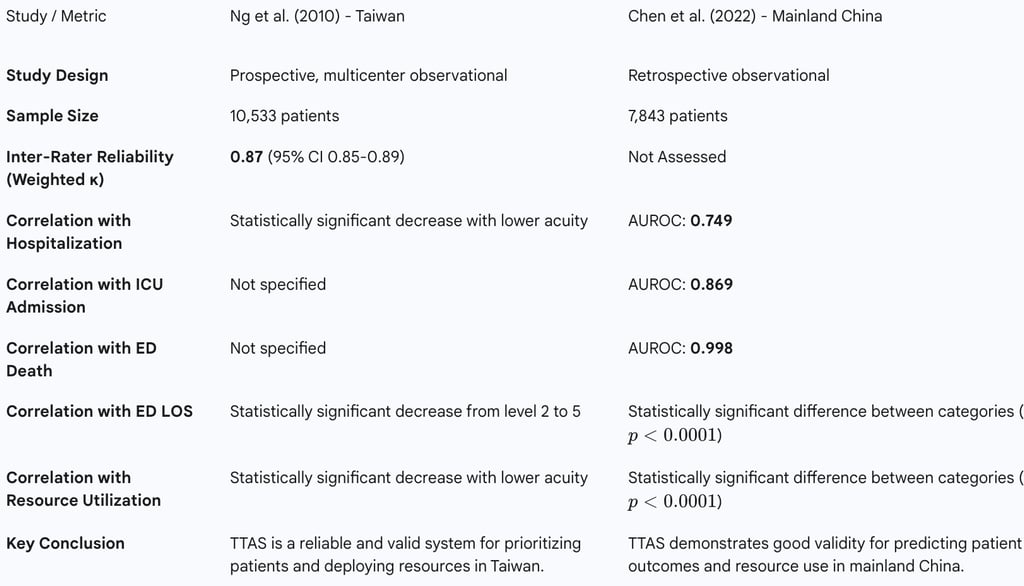

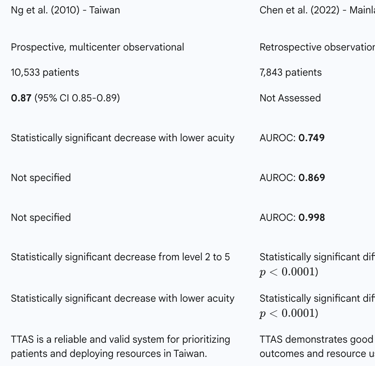

The study reported a weighted kappa statistic for TTAS assignment of 0.87, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.85 to 0.89. In clinical and epidemiological research, a kappa value between 0.81 and 1.00 is considered "almost perfect" agreement. This exceptionally high value confirms that the TTAS, when used with its computerized decision support tool, is a highly reliable and reproducible system. It demonstrates that the structured methodology and clear definitions within the TTAS framework effectively minimize subjective interpretation and lead to consistent triage decisions across different nurses and hospital settings.

Validation Against Clinical Outcomes

Beyond reliability, a triage system must demonstrate validity by proving that its acuity levels are meaningful predictors of patient outcomes and healthcare needs. The TTAS has been extensively validated against several key performance indicators, confirming that a higher TTAS level is strongly associated with more severe illness and a greater need for intensive care.

Correlation with Hospitalization and ICU Admission Rates

One of the most direct measures of a triage system's validity is its ability to predict the need for hospital admission. Multiple studies have shown a strong, statistically significant, and graded relationship between TTAS level and the probability of hospitalization. As the TTAS acuity level decreases, the rate of hospital admission also decreases progressively. This indicates that the scale is successfully identifying the sickest patients who will require inpatient care.

The predictive power of TTAS is even more pronounced for the most critical outcomes. A study evaluating the TTAS's performance in mainland China used the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curve to quantify its predictive accuracy. The AUROC for predicting hospital admission was a respectable 0.749. More impressively, the AUROC for predicting admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) was 0.869, and for predicting death in the ED, it was an almost perfect 0.998. These results demonstrate that the TTAS is not only valid for general admissions but is exceptionally accurate at identifying patients at the highest risk of critical illness and mortality.

Predictive Power for ED Length of Stay (LOS) and Medical Resource Utilization

An efficient triage system should also help manage patient flow and resource allocation by accurately stratifying patients based on the expected intensity of their care. The TTAS has been shown to be highly effective in this regard. The initial validation study found a statistically significant decrease in the mean ED length of stay (LOS) as the TTAS level fell from 2 to 5. This shows that the system correctly identifies patients with less urgent conditions who can be managed and discharged more quickly, a crucial factor in mitigating ED overcrowding.

Similarly, there is a strong, graded correlation between TTAS level and the consumption of medical resources. The mean cost of care and the number of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions decrease significantly with each step down in the TTAS acuity scale. This confirms that the TTAS is a valid tool for predicting resource utilization, allowing hospital administrators and clinical leaders to better anticipate departmental needs and allocate resources more efficiently. The ability to avoid "overtriage"—assigning an inappropriately high acuity level—is a key strength, as it prevents the misdirection of limited resources to less sick patients.

International Applicability: A Case Study of TTAS Validation in Mainland China

A critical question for any nationally developed clinical system is whether its validity is confined to its original healthcare context or if it is robust enough to be generalizable. The TTAS, itself an adaptation of a Canadian system, provided an opportunity to test this principle of portability. A 2022 retrospective study evaluated the performance of the TTAS in a tertiary hospital in mainland China, a different and much larger healthcare system.

The results of this study were a powerful endorsement of the TTAS's underlying clinical logic. The scale maintained its strong predictive validity, showing significant correlations with patient disposition, hospital and ICU admission, ED LOS, and resource utilization, with performance metrics comparable to those observed in Taiwan. This successful "export" and re-validation demonstrates that the TTAS framework—based on a systematic assessment of chief complaints and clinical modifiers—is not dependent on the unique characteristics of the Taiwanese healthcare system. It functions as a robust and effective clinical tool in other high-volume, tertiary care ED settings. This finding suggests that the TTAS can be considered a mature, validated model that other health systems, particularly those in Asia seeking to adopt a standardized five-level triage scale, could implement or adapt with a high degree of confidence in its clinical efficacy.

Table 2: Summary of TTAS Validation Studies and Key Performance Metrics

Comparative Analysis with International Triage Systems

TTAS vs. Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS): A Detailed Comparison of the Adaptation

The TTAS is fundamentally an adaptation of the CTAS, designed to fit the clinical and cultural context of Taiwan. While it retains the core five-level structure and the complaint-based methodology of its Canadian predecessor, the TTAS National Working Group, composed of emergency medicine experts, made several deliberate modifications to optimize its local performance and relevance. These adaptations highlight the critical process of localizing an international standard rather than simply translating it.

Key Modifications

The most significant adaptations are evident in the pediatric version of the scale (Ped-TTAS), which was developed in parallel with the adult system.

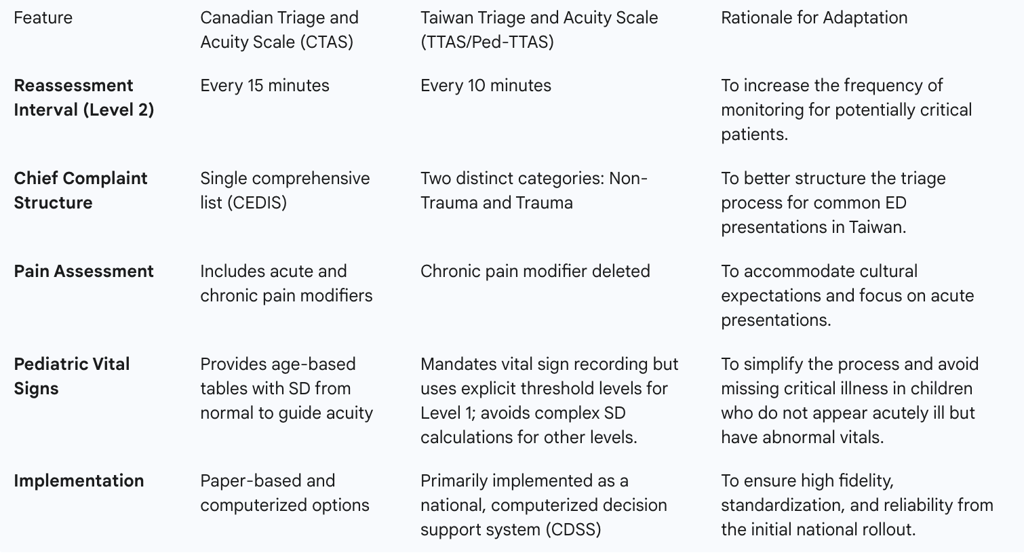

Reassessment Intervals: The TTAS mandates shorter, more aggressive reassessment time intervals for waiting patients compared to the CTAS guidelines. For example, a TTAS Level 2 (Emergent) patient should be reassessed within 10 minutes, whereas the CTAS standard is 15 minutes. This reflects a policy decision to increase the frequency of monitoring for potentially critical patients in the waiting room.

Chief Complaint Structure: While CTAS uses a single comprehensive list of presenting complaints (the Canadian Emergency Department Information System, or CEDIS list), the TTAS organizes its extensive list into two primary categories: Non-Trauma and Trauma. This structural change was intended to better organize the triage workflow for the most common types of ED presentations in Taiwan.

Pain Scale Revisions: In a notable cultural adaptation, the Ped-TTAS developers made the decision to delete "chronic pain" as a specific modifier. This change was made to accommodate cultural expectations in Taiwan and to sharpen the tool's focus on acute, emergency conditions rather than the management of chronic pain syndromes in the ED.

Pediatric Vital Signs: The approach to pediatric vital signs represents a significant philosophical divergence. The Paediatric CTAS provides nurses with detailed age-based tables of normal vital signs and uses the number of standard deviations from the norm to help guide acuity selection. The TTAS National Working Group viewed this as potentially complex and opted for a simpler, more direct approach. The Ped-TTAS mandates that vital signs be recorded for all pediatric patients but uses explicit, absolute threshold values to define a Level 1 (Resuscitation) condition. This was done to ensure that critical illness defined by severe vital sign abnormalities was never missed, even in a child who did not initially appear acutely ill.

Comparative Performance

Early research in Taiwan that directly compared the performance of the original CTAS model against the then-current four-level TTS was instrumental in the decision to adopt the five-level framework. These studies consistently found that the CTAS model provided superior discrimination for ED patient triage and that its assigned acuity levels correlated better with hospitalization rates, LOS, and medical resource consumption. This body of evidence confirmed that the core logic of the CTAS was more valid and effective in the Taiwanese context than the incumbent system, providing a strong rationale for its adoption and subsequent adaptation into the TTAS.

Table 3: Key Adaptations of CTAS in the Development of TTAS and Ped-TTAS

TTAS in Specialized Scenarios: The Contrast with START for Mass Casualty Incidents (MCIs)

A crucial aspect of evaluating any triage system is understanding its operational limits and its fitness for purpose in different scenarios. While the TTAS is a highly effective tool for managing the daily flow of individual patients in an ED, its design presents significant challenges in the context of a Mass Casualty Incident (MCI), such as a large-scale earthquake, industrial accident, or terrorist attack. The comprehensive, complaint-based assessment required by TTAS is inherently time- and labor-consuming, making it impractical when a large number of victims arrive at the ED simultaneously and resources are overwhelmed.

To investigate this, a retrospective study was conducted following the 2018 Hualien earthquake in Taiwan. Researchers compared the performance of the TTAS, which was used in real-time at the receiving hospital, with the Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) protocol, which was applied retrospectively to the same patient records. START is a rapid triage system designed specifically for MCIs, sorting victims into four categories (Minor, Delayed, Immediate, Deceased) based on a quick assessment of only three physiological parameters: respirations, perfusion (pulse), and mental status.

The study yielded a profound finding: despite their vastly different methodologies, both TTAS and START demonstrated nearly identical accuracy in predicting the primary patient outcome of ED disposition (i.e., whether a patient was admitted or discharged). The AUROC for predicting disposition was 0.709 for both systems. This result illuminates a critical trade-off between triage precision and speed. The extra time and clinical detail required for a TTAS assessment did not translate into a more accurate sorting of patients for disposition in an MCI environment. The much faster, physiologically-based START protocol achieved the same predictive power.

This does not imply that TTAS is a flawed system, but rather that it is a specialized tool designed for a different purpose. In routine ED operations, the detailed assessment of TTAS is invaluable for accurate individual patient prioritization and resource planning. However, in an MCI, the primary goal shifts from individual diagnostic precision to rapid population-level sorting to identify those in need of immediate life-saving interventions. For this task, a system optimized for speed, like START, is superior. This analysis underscores that a comprehensive emergency preparedness plan requires a dual-system approach: a robust, detailed system like TTAS for daily operations, and a separate, validated rapid triage protocol like START to be activated in the event of a disaster.

Application in Special Populations: The Paediatric TTAS (Ped-TTAS)

Rationale for a Specialized Pediatric Scale

The triage of pediatric patients presents unique challenges that cannot be adequately addressed by adult-focused triage systems. Children are not simply small adults; their physiology, developmental stages, and patterns of illness and injury differ significantly. Normal vital signs, such as heart rate and respiratory rate, vary dramatically with age. Furthermore, children, particularly infants and toddlers, may be unable to articulate their symptoms, requiring the triage nurse to rely more heavily on observational skills and parental reports. Using an adult triage scale for children can lead to inaccurate acuity assignments, potentially resulting in both over-triage (unnecessary resource utilization) and under-triage (delaying care for a critically ill child).

Recognizing these challenges, and in alignment with the development of the adult TTAS, a dedicated Paediatric Triage and Acuity Scale (Ped-TTAS) was developed in Taiwan. The explicit goal was to create a standardized, validated tool to prioritize pediatric patients rapidly and accurately, ensuring that their critical medical needs are met in a timely manner and that ED resources are utilized appropriately.

Key Adaptations from the Paediatric CTAS

The Ped-TTAS was developed by adapting the Paediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (Paed-CTAS) to be more pertinent to ED conditions and clinical practices in Taiwan. An 11-member expert panel, comprising specialists from the Taiwan Society of Emergency Medicine and the Taiwan Association of Critical Care Nurses, oversaw this adaptation process, ensuring that all modifications were based on consensus and had high content validity.

The key adaptations, as detailed previously, included the implementation of shorter reassessment intervals, the restructuring of chief complaints into non-trauma (12 categories, 74 complaints) and trauma (15 categories, 47 complaints) domains, and the culturally-informed revision of the pain scale. A particularly important modification was the approach to vital signs. Instead of relying on complex tables of age-based norms, the Ped-TTAS established explicit vital sign thresholds for different age groups (0–3 months, >3 months to 3 years, and >3 years) that would automatically classify a patient as Level 1, simplifying the decision-making process for the most critical patients. To support the consistent application of this new tool, an electronic clinical decision support system, ePed-TTAS, was developed and implemented concurrently.

Validated Effectiveness in Improving Patient Safety and Resource Allocation in Pediatric Emergencies

The effectiveness of the five-level Ped-TTAS was validated by comparing its performance to the four-level Paediatric Taiwan Triage System (Ped-TTS) that it replaced. A study analyzing data from before and after the 2010 implementation found a significant difference in patient prioritization between the two systems. The five-level Ped-TTAS demonstrated improved differentiation in predicting both hospitalization rates and medical costs, indicating that it was better able to discriminate pediatric patients by acuity.

Further research has confirmed that the TTAS is a reliable triage tool for the particularly challenging population of pediatric trauma patients. The study found a significant positive correlation between the assigned TTAS acuity level and major outcomes such as hospitalization, ED length of stay, and the need for emergency surgery. The introduction of this more accurate and precise pediatric triage system is considered a significant step forward for patient safety in Taiwan, enabling more timely and appropriate utilization of ED resources for children.

The Human Element: The Triage Nurse's Role in the TTAS Framework

Factors Influencing Triage Decision-Making: Experience, Environment, and Patient Status

While the computerized TTAS provides a standardized and objective framework, the act of triage remains a complex cognitive process performed by a human clinician. The final triage decision is not merely the output of an algorithm but the product of an interaction between the tool, the patient, and the nurse. Qualitative research conducted with triage nurses in Taiwan has identified three main categories of factors that influence their decision-making practices within the TTAS system.

Nurses' Experiences: This is a critical internal factor. The nurse's level of clinical experience, their critical thinking skills, their ability to synthesize information quickly, and their familiarity with the TTAS system all play a significant role in the accuracy and efficiency of the triage assessment.

Patients' Health Status: This encompasses the objective clinical data—the patient's vital signs, physical presentation, and stated complaints—that serve as the primary inputs for the TTAS algorithm.

External Environmental Factors: The context in which triage occurs has a profound impact. Factors such as the level of ED crowding, the physical layout of the triage area, the degree of patient privacy that can be maintained, and the effectiveness of communication with patients and their relatives can all influence the triage process.

Understanding these interacting factors is crucial for optimizing the triage process. It highlights that simply implementing a good algorithm is not enough; the system must also support the clinician and account for the realities of the ED environment.

The Value of Clinical Judgment: Nurse-Initiated Modification and Its Impact on Accuracy

A common concern with highly standardized, computer-assisted clinical protocols is that they might devalue or supplant the clinical judgment of experienced professionals. However, research on the TTAS suggests a more symbiotic relationship. The system is designed not to replace clinical judgment, but to guide and augment it.

A compelling study on the use of TTAS for pediatric trauma patients explicitly investigated the impact of nurse-initiated modifications to the initial, algorithm-generated triage level. The study found that when well-experienced triage nurses used their professional judgment to override the system's initial recommendation (either up-triaging or down-triaging the patient), the overall predictive performance of the triage system improved. This was demonstrated statistically by a decrease in the Akaike information criterion and an increase in C-statistics for key outcomes after the nurse modifications were applied.

This finding is of profound importance. It indicates that while the TTAS algorithm provides a highly reliable and valid baseline, it cannot always capture the subtle clinical nuances or the overall "gestalt" that an experienced nurse can perceive. The optimal application of the TTAS is therefore a synthesis of the algorithm's standardized logic and the clinician's irreplaceable expertise. The system provides the robust, evidence-based foundation, while the nurse's judgment provides the final layer of clinical refinement. This demonstrates that the TTAS framework is most powerful when it empowers, rather than constrains, the skilled professionals who use it.

Challenges and Educational Imperatives for Triage Professionals

The complex role of the triage nurse brings with it significant challenges. Nurses must not only perform a rapid and accurate clinical assessment but also manage communication with anxious patients and families, maintain patient privacy in a typically open and busy environment, and make high-stakes decisions under pressure. The research highlights the need for ongoing support and education for these critical frontline professionals.

Recommendations arising from studies of the TTAS in practice call for a multi-pronged approach. First, there is a need to continually improve the critical thinking skills of triage nurses through targeted education and training. This training should focus not just on the mechanics of the TTAS algorithm but on the higher-order cognitive skills needed to apply it effectively in complex situations. Second, hospital administrators should address environmental factors, such as ensuring adequate patient privacy at the triage desk, to create a setting more conducive to high-quality assessment. Finally, there is a recognized need for public education to help patients and families understand the purpose of triage and the rationale behind waiting times, which can help manage expectations and create a more efficient and less confrontational triage process.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Summary of TTAS Strengths

After more than a decade of nationwide use and rigorous evaluation, the Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale has established a clear record of strengths that position it as a mature and highly effective system for emergency department triage.

Enhanced Patient Discrimination: The five-level structure of the TTAS provides a significant improvement in patient stratification compared to the four-level TTS it replaced. It successfully resolves the issue of clustering large numbers of patients into ambiguous middle-acuity categories, allowing for more precise and meaningful prioritization.

Proven Validity and Reliability: The TTAS is supported by robust scientific evidence. It has demonstrated "almost perfect" inter-rater reliability, with a weighted kappa of 0.87, ensuring consistent application. Its validity is confirmed by strong, statistically significant correlations with a range of critical patient outcomes, including hospitalization rates, ICU admission, ED length of stay, and medical resource utilization.

System Standardization via Computerization: The implementation of TTAS as a national, computerized decision support system is a key strength. This approach ensures a high degree of standardization and objectivity in triage assessments across the entire country, promoting equitable care and facilitating large-scale data collection for quality improvement and research.

International Portability and Robustness: The successful validation of the TTAS in a different healthcare system (mainland China) demonstrates that its core clinical logic is robust and not limited to the Taiwanese context. This establishes the TTAS as an exportable model for other health systems seeking to implement a validated five-level triage scale.

Acknowledged Limitations

No clinical system is without limitations, and a comprehensive analysis requires an objective assessment of the TTAS's known weaknesses and areas where it is less effective.

Suboptimal Performance in Mass Casualty Incidents (MCIs): The most significant limitation of the TTAS is its unsuitability for use in MCI scenarios. Its detailed, complaint-based assessment process is too time-consuming and resource-intensive when faced with a sudden influx of a large number of victims. In these situations, a faster, physiologically-based system like START is more appropriate.

Potential for Overtriage in Specific Populations: While generally accurate, the TTAS is not immune to overtriage. One study suggested that the presence of mild to moderate pain might negatively impact the scale's ability to predict the need for hospitalization, potentially leading to the assignment of an unnecessarily high acuity level for some patients in pain.

Reliance on Chief Complaints: The TTAS is fundamentally a complaint-based system. While effective, this approach may have limitations, particularly in trauma care where the initial complaint may not fully capture the extent of physiological derangement. A recent study on trauma patients found that while the TTAS is reliable, its prioritization performance could be significantly improved by combining it with a physiological shock index (the rSI-sMS), which yielded a superior ability to predict adverse outcomes. This suggests that relying on chief complaints alone may not be the optimal strategy for all patient populations.

Future Outlook: Integration of Machine Learning, Advanced Physiological Scores, and Continuous Refinement

The future development of the TTAS is likely to focus on addressing its limitations and leveraging its strengths. The existence of a national, standardized, digital dataset of triage information creates a uniquely powerful resource for innovation.

Machine Learning and Predictive Analytics: The vast amount of data generated by the computerized TTAS is an ideal substrate for developing and validating machine learning models. Such models could potentially predict patient disposition, risk of deterioration, or other clinical outcomes with even greater accuracy than the current algorithm alone, providing an additional layer of decision support for triage nurses.

Integration of Advanced Physiological Scores: The finding that combining the TTAS with a physiological score improves performance in trauma triage points toward a promising avenue for refinement. Future versions of the TTAS could incorporate dynamic, real-time physiological data or validated risk scores for specific conditions to create a more hybrid system that combines the strengths of both complaint-based and physiological assessment.

Continuous Refinement: Like its parent system, the CTAS, the TTAS is not a static tool. The ongoing collection and analysis of performance data will allow for continuous, evidence-based refinement of the chief complaint lists, modifier definitions, and underlying algorithm to ensure it remains aligned with evolving clinical practice and continues to serve the needs of patients and clinicians in Taiwan.

Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

Synthesis of Findings: The TTAS as a Mature and Effective Triage System

The Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale represents a landmark achievement in the standardization and modernization of emergency care in Taiwan. Born from the recognized need to replace an underperforming four-level system, the TTAS was developed through the methodical and thoughtful adaptation of a leading international standard, the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale. Its implementation as a national, computerized decision support system from its inception in 2010 was a strategic masterstroke, ensuring a high degree of standardization, reliability, and data-generating capability that has underpinned its success.

The body of evidence is clear and compelling: the TTAS is a highly reliable and valid clinical tool. It has demonstrated exceptional inter-rater consistency and its five acuity levels are powerful, statistically significant predictors of critical patient outcomes, including hospitalization, ICU admission, length of stay, and resource utilization. Its successful validation in other healthcare contexts confirms the robustness of its clinical logic. While it has acknowledged limitations, particularly in mass casualty scenarios, the TTAS stands as a mature, effective, and evidence-based system that has fundamentally improved patient safety and operational efficiency in Taiwan's emergency departments. It serves as an exemplary model of how a health system can successfully adopt and localize an international best practice to meet its specific needs.

Recommendations for Health Systems Considering Triage Scale Adoption or Revision

Based on the analysis of the TTAS's development and performance, several strategic recommendations can be offered to health system leaders, policymakers, and hospital administrators who are considering the adoption or revision of an ED triage system.

Prioritize a Validated Five-Level Scale: The evidence strongly supports the superiority of five-level triage scales over less granular systems. Adopting a five-level structure is essential to ensure adequate patient discrimination and effective prioritization in modern, high-volume EDs.

Adapt, Don't Reinvent: Rather than developing a new triage system de novo, health systems should strongly consider adapting a well-established international system with a strong evidence base, such as the CTAS or ESI. This approach leverages a global body of research and validation. However, the adaptation process must be deliberate and context-specific, involving local clinical experts to ensure the final tool is relevant to local patient populations, clinical practices, and cultural norms.

Embrace a Digital-First Implementation: The success of the TTAS is inextricably linked to its computerized nature. Implementing a new triage scale with an integrated computerized decision support system from the outset is critical for maximizing standardization, ensuring high-fidelity application, reducing variability, and creating a robust data infrastructure for ongoing quality improvement and research.

Develop a Dual-System Strategy for Emergency Preparedness: Recognize that a single triage system cannot be optimal for all scenarios. In addition to a comprehensive ED triage system like TTAS for routine operations, all health systems must develop and implement a separate, validated rapid triage protocol (e.g., START) as a core component of their mass casualty and disaster preparedness plans.

Recommendations for Clinical Practice and Triage Nurse Training

To maximize the effectiveness of the TTAS or any similar triage system at the clinical level, the following recommendations are crucial.

Focus Training on Critical Thinking, Not Just Algorithm Mechanics: Triage education must evolve beyond rote memorization of the triage algorithm. Training programs should use methods like simulation and case-based learning to develop and enhance the higher-order critical thinking and clinical judgment skills of triage nurses.

Empower and Value Clinical Judgment: Hospital policies and clinical culture should recognize that an experienced nurse's judgment is a valuable asset that can enhance the accuracy of a standardized system. A framework should be established that empowers experienced nurses to make clinically justified modifications to the initial triage score, with a clear process for documentation and review.

Implement Robust Quality Improvement Cycles: The data collected by a computerized triage system should be actively used. Hospitals should implement regular, data-driven quality improvement and audit programs to provide constructive feedback to triage nurses, identify systemic trends (e.g., consistent over- or under-triage of specific conditions), and inform continuous refinement of both the triage process and educational initiatives.