The Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS): A Comprehensive Analysis of Its Evolution, Efficacy, and Role in Modern Emergency Healthcare

The Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) stands as a pivotal four-level emergency classification system designed to prioritize patient care in emergency departments (EDs) and pre-hospital settings. Initially introduced in 1997, the scale demonstrated moderate reliability and a concerningly high rate of undertriage.

The Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) stands as a pivotal four-level emergency classification system designed to prioritize patient care in emergency departments (EDs) and pre-hospital settings. Initially introduced in 1997, the scale demonstrated moderate reliability and a concerningly high rate of undertriage, reaching up to 31%, primarily due to a lack of standardization in vital sign assessment. In response to these critical limitations, SETS underwent a significant revision. This revision focused on establishing a systematic and standardized approach to the measurement and interpretation of vital signs during the triage process.

The impact of this revision has been profound, transforming SETS into a highly reliable and accurate triage instrument. Empirical evaluations of the revised scale have consistently shown substantial inter-rater reliability, with a mean kappa (κ) of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.60–0.78), and almost perfect test-retest reliability, indicated by a mean κ of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.84–0.88). Furthermore, the revised SETS achieved a high rate of correct triage at 84.1%, significantly reducing undertriage to 7.2% and overtriage to 8.7%. A crucial finding from these evaluations is the independent predictive power of vital sign measurement for correct triage, with an odds ratio of 1.29 for each additional vital sign measured.

The successful evolution of SETS from a system with moderate reliability to one demonstrating high reliability and low rates of mistriage underscores the critical importance of standardization, particularly in the objective measurement and interpretation of vital signs. The initial version of SETS, despite its widespread adoption, was hindered by a lack of consistent protocols for vital sign assessment, leading to significant variability in triage decisions and a high proportion of patients being undertriaged. The targeted revision, which meticulously standardized these objective clinical data points, directly addressed this fundamental flaw. This systematic improvement in data collection and interpretation protocols was not merely a procedural adjustment; it was a foundational enhancement that directly led to improved accuracy and consistency in patient classification. This progression illustrates that the robustness of objective data collection and interpretation within a triage system is a primary determinant of its effectiveness, directly enhancing patient safety by minimizing misclassification risks and optimizing the allocation of emergency resources.

Beyond the hospital environment, SETS has also demonstrated excellent reliability and high accuracy in pre-hospital settings when utilized by paramedics. A study involving paramedics reported an overall intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for triage level of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.77–0.99), with 89% of cases assigned the correct emergency level. This performance suggests that SETS can be safely and effectively employed by paramedics in Switzerland to determine emergency levels and guide patients to the most appropriate medical facility. The scale's widespread use in Switzerland, France, and Belgium since 1997, coupled with its recommendation by the Swiss Society of Emergency and Rescue Medicine, solidifies its position as a robust and essential tool in modern emergency healthcare.

Introduction to Emergency Triage and the Swiss Context

In the dynamic and often chaotic environment of emergency departments (EDs), triage serves as an indispensable process for managing patient flow and ensuring that individuals with the most critical conditions receive timely medical attention. Triage, derived from the French word meaning "to sort" or "to choose," is fundamentally about establishing priorities for treatment among a diverse group of patients arriving at Accident and Emergency (A&E) Departments. This critical sorting function is typically performed by experienced registered nursing staff who employ systematic and scientific methodologies to assess patients' clinical conditions, interpret presenting features, and initiate early interventions to prevent clinical deterioration or death. The implementation of such a system is crucial for determining the relative urgency of individual patient needs, ensuring that emergency cases receive immediate treatment while those with non-acute symptoms are appropriately managed with longer waiting times.

Globally, the landscape of emergency triage systems varies significantly. In regions such as North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia, five-level triage instruments are widely adopted and serve as the standard for categorizing patients. These systems, like the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) in the United States or the Manchester Triage Scale (MTS) in the UK, typically classify patients into categories ranging from critical to non-urgent, each with defined time objectives for medical assessment.

In contrast, the European context presents a more fragmented picture, with fewer countries, particularly French-speaking ones, having developed and universally adopted a standardized triage system. This regional disparity highlights a significant gap in standardized emergency care protocols across parts of Europe. Within this unique European landscape, the Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) emerges as a notable exception and a significant achievement. SETS, a four-level triage scale, has been in continuous use by numerous EDs across Switzerland, France, and Belgium since 1997. Its widespread adoption in these countries, despite the broader European trend, underscores its recognized utility and its role in filling a critical need for a structured approach to emergency patient prioritization. The successful implementation and demonstrated efficacy of SETS in this complex, multi-lingual, and often decentralized European environment could therefore serve as a valuable model for other nations seeking to enhance their emergency care protocols, improve patient flow, and ultimately bolster patient safety.

The Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS): Foundations and Evolution

A. Initial Development and Rationale

The Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) was first introduced in 1997 and rapidly gained adoption in numerous emergency departments across Switzerland, France, and Belgium. Its initial development was driven by the pressing need for a structured approach to patient prioritization in increasingly overcrowded EDs, aiming to streamline patient flow and ensure timely care. However, early evaluations of this four-level scale revealed significant limitations in its performance. These studies indicated only moderate reliability and, more critically, a high rate of undertriage, which was reported to be as high as 31%. Undertriage, the underestimation of a patient's acuity, can lead to dangerous delays in treatment for critically ill or injured individuals, posing substantial risks to patient outcomes.

The primary factor identified as contributing to this suboptimal performance was a pronounced lack of standardization within the triage process itself. Specifically, there was considerable variability in how vital signs were measured and interpreted by different triage nurses. This inconsistency meant that the same clinical presentation could be assigned different urgency levels depending on the individual clinician performing the triage, leading to unreliable classifications and a higher incidence of mistriage. The candid acknowledgment of SETS's "moderate reliability and high rates of undertriage (31%)" in its initial form, directly attributing these issues to a "lack of standardization, especially vital sign measurement and interpretation," reflects a mature, evidence-based approach to the development and refinement of clinical tools. The initial widespread adoption of SETS, even with these known limitations, indicated an urgent demand for a triage system. However, the subsequent decision to revise the scale, specifically targeting the inconsistencies in vital sign assessment as the root cause of its suboptimal performance, demonstrates a critical and self-correcting scientific methodology. This proactive identification and precise remediation of a core flaw, rather than merely accepting the existing limitations, signifies a strong commitment to continuous quality improvement in emergency care. The broader implication for any clinical protocol, particularly one as vital as triage, is that ongoing rigorous evaluation and a willingness to adapt based on empirical evidence are indispensable for ensuring long-term efficacy, patient safety, and optimal clinical outcomes.

B. The Revised SETS: Standardization and Key Enhancements

Recognizing the critical need to address the identified shortcomings, the Swiss Emergency Triage Scale underwent a comprehensive revision. The central imperative behind this revision was to significantly improve the standardization of vital sign measurement and their subsequent interpretation during the triage process. The developers hypothesized that by implementing a systematic and standardized procedure for assessing and interpreting vital signs, the overall triage performance would demonstrably improve. This strategic focus on vital signs stemmed from their recognized importance in modern triage instruments for accurately categorizing patients and promptly identifying life-threatening conditions.

A cornerstone of the evaluation and validation of the revised SETS was the establishment of a "gold standard" for triage decisions. This gold standard was meticulously attributed by an expert panel, ensuring a robust and objective benchmark against which the performance of the revised scale could be measured. The process involved comparing triage decisions made by participating nurses with the expert-attributed acuity levels, allowing for precise calculation of correct triage, undertriage, and overtriage rates. This reliance on a "gold standard attributed by an expert panel" for evaluating the revised SETS performance highlights a commitment to methodological rigor and objective validation in clinical tool development. The use of an expert consensus as the benchmark for correct triage decisions ensures that the evaluation is grounded in established clinical expertise, providing a credible and reliable measure of the scale's accuracy. This approach is fundamental to building confidence in the tool's effectiveness, as it moves beyond subjective assessments to a validated standard. Such a rigorous validation process is essential for any medical instrument, particularly one that directly influences patient care pathways and outcomes, as it provides a clear, evidence-based foundation for its utility and safety in practice.

The development and evaluation of the revised SETS were a collaborative effort involving several key contributors. The authors of the study evaluating the revised scale include Olivier T Rutschmann, Olivier W Hugli, Christophe Marti, Olivier Grosgurin, Antoine Geissbuhler, Michel Kossovsky, Josette Simon, and François P Sarasin. These individuals, affiliated with departments of Community, Primary Care and Emergency Medicine, Interdisciplinary Centers and Medical Logistics, Medical Imaging and Information Sciences, and Internal Medicine, Rehabilitation and Geriatrics across various Swiss university hospitals, brought a multidisciplinary expertise to the revision and validation process. Their collective work was instrumental in refining the SETS algorithm to incorporate standardized vital sign interpretation, thereby addressing the critical need for improved reliability and accuracy in emergency triage.

Structure and Application of the Revised SETS

The revised Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) is a symptom-based, four-level triage scale meticulously designed to incorporate timeliness objectives for patient assessment and treatment. This structured approach ensures that patients are categorized not only by the severity of their condition but also by the urgency with which they require medical intervention.

A. Triage Levels and Time Objectives

The four distinct levels of SETS are defined by specific clinical significance and corresponding time targets for medical evaluation and treatment. These objectives are crucial for guiding the immediate actions of emergency department staff and for managing patient expectations regarding waiting times.

SETS Level 1 is reserved for patients presenting with life-threatening or limb-threatening situations, necessitating immediate assessment and treatment. This category demands the highest priority, reflecting the critical nature of the patient's condition where any delay could lead to irreversible harm or death. SETS Level 2 encompasses potentially life-threatening situations, where prompt medical attention is still crucial, with the objective of assessment and treatment occurring within 20 minutes. This level acknowledges conditions that, while not immediately fatal, could rapidly deteriorate without timely intervention. SETS Level 3 applies to urgent but not immediately life-threatening conditions, for which assessment and treatment are mandated within 120 minutes. This category balances clinical urgency with resource availability, ensuring that patients with significant but stable conditions are seen within a reasonable timeframe. Finally, SETS Level 4 is designated for non-urgent conditions, where patients can expect a longer waiting time as their medical needs are not acute or immediately critical. This stratification allows emergency departments to efficiently allocate resources and manage patient flow, prioritizing those with the most severe needs.

B. Detailed Clinical Criteria and Vital Sign Integration

The classification of patients into these four SETS levels is primarily driven by a symptom-based approach, complemented by a systematic and standardized measurement and interpretation of vital signs. Triage nurses begin by identifying the patient's main presenting complaint from a predetermined list. Based on this complaint, one or more emergency levels may be initially considered. The crucial step then involves the measurement and interpretation of vital signs, which serve to further refine the triage decision and attribute the most appropriate emergency level. Nurses are specifically trained to measure vital signs when the main complaints could be associated with multiple emergency levels, ensuring a data-driven approach to patient categorization.

The revised SETS incorporates a comprehensive set of vital sign parameters, each with specific thresholds that guide the assignment of a triage level. These parameters are fundamental to objectively assessing a patient's physiological state and identifying signs of instability or severe illness.

For example, a patient with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 8 or less would be immediately triaged to Level 1, indicating a life-threatening condition requiring urgent intervention. Similarly, a heart rate below 40 beats per minute or above 150 beats per minute would also trigger a Level 1 assignment. Conversely, a GCS of 14 or 15, a heart rate between 51 and 129 bpm, and a systolic blood pressure between 91 and 180 mmHg (with diastolic below 115 mmHg) would typically lead to a Level 3 or 4 classification, assuming no other critical vital sign abnormalities. The shock index (heart rate divided by systolic blood pressure) is also a critical parameter; a value greater than 1 indicates a higher level of urgency, typically Level 2. The inclusion of these detailed physiological parameters and their precise thresholds ensures a systematic and objective assessment, reducing subjective variability in triage decisions.

C. Role of Presenting Complaints

While vital signs provide objective physiological data, the initial assessment in SETS is guided by the patient's main presenting complaint. This symptom-based approach allows nurses to quickly narrow down potential emergency levels. A predetermined list of presenting complaints is utilized, and for each complaint, one or more emergency levels may be attributed based on the subsequent vital sign measurements.

Examples of how presenting complaints guide the triage process include:

Cardiac arrest immediately mandates a SETS Level 1 designation, reflecting the absolute urgency of the situation.

Complaints such as Tachycardia or Shortness of breath can span multiple emergency levels (1, 2, or 3), depending on the accompanying vital signs and clinical context. For instance, severe shortness of breath with low oxygen saturation would escalate to Level 1, whereas moderate shortness of breath with stable vital signs might be Level 2 or 3.

Confusion or Altered consciousness typically indicate more severe conditions, often leading to Level 1 or 2 classifications.

Less acute symptoms like Abdominal pain or Urinary retention might be triaged as Level 2 or 3, depending on severity and associated vital signs.

Dysuria could be Level 3 or 4, while a request for Prescription renewal would almost certainly fall into the non-urgent Level 4 category.

This dual approach, combining presenting complaints with rigorous vital sign assessment, ensures that the triage process is both comprehensive and efficient, allowing for a rapid yet accurate determination of a patient's emergency level.

Empirical Evidence: Reliability and Performance of the Revised SETS

The effectiveness of any triage system hinges on its reliability and accuracy in classifying patients. The revised Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) has undergone rigorous evaluation to assess these critical performance metrics, demonstrating significant improvements over its initial iteration.

A. Inter-rater and Test-retest Reliability

Reliability in triage refers to the consistency of decisions. Inter-rater reliability assesses the agreement between different healthcare professionals when triaging the same patient, while test-retest reliability measures the consistency of triage decisions made by the same professional over time. High reliability is crucial for ensuring uniform patient care and equitable resource allocation.

Studies evaluating the revised SETS have demonstrated robust reliability. In a significant study involving 58 triage nurses evaluating 30 clinical scenarios twice over a three-month interval, 3387 triage situations were analyzed. The inter-rater reliability of the revised SETS showed substantial agreement, with a mean kappa (

κ) coefficient of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.60–0.78). This indicates that different nurses applying the revised scale consistently arrived at similar triage decisions for the same patient presentations. Furthermore, the test-retest reliability of the revised scale exhibited almost perfect agreement, with a mean κ of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.84–0.88). This high level of consistency by individual nurses over time confirms the stability and reproducibility of the revised SETS. These reliability figures are comparable to, or in some cases, exceed those reported for other well-established international triage instruments, positioning the revised SETS among the best-validated scales globally.

B. Accuracy of Triage: Rates of Correct Triage, Undertriage, and Overtriage

Beyond consistency, the accuracy of a triage system—its ability to correctly classify patients according to their true clinical urgency—is paramount for patient safety and efficient emergency department operations. Accuracy is typically assessed by comparing triage decisions against a "gold standard" attributed by an expert panel.

The evaluation of the revised SETS revealed a high rate of correct triage. A perfect concordance between the triage levels assigned by the evaluators and the gold standard was observed in 84.1% of the situations analyzed. This high percentage indicates that the revised SETS accurately identifies the appropriate urgency level for the vast majority of patients.

Equally important are the rates of mistriage: undertriage and overtriage. Undertriage occurs when a patient's acuity is underestimated, potentially leading to delayed care for critical conditions. Overtriage, conversely, involves overestimating acuity, which can unnecessarily consume resources and increase waiting times for other patients. The revised SETS demonstrated low rates of mistriage: the rate of undertriage was 7.2%, and the rate of overtriage was 8.7%. These figures represent a substantial improvement compared to the initial version of SETS, which had an undertriage rate as high as 31%. The observed rates of undertriage and overtriage with the revised SETS are also similar to or lower than those achieved with other prominent triage scales, reinforcing its strong performance.

C. Predictors of Correct Triage: The Critical Role of Vital Signs

A significant finding from the studies on the revised SETS is the identification of vital sign measurement as an independent predictor of correct triage. The analysis showed that for each additional vital sign measured, the odds of correct triage increased by a factor of 1.29 (95% CI: 1.20–1.39). This quantitative evidence underscores the profound impact of comprehensive and standardized vital sign assessment on the accuracy of triage decisions. The systematic integration of vital sign interpretation into the revised SETS algorithm, which was a key enhancement, directly contributed to its improved performance.

This finding highlights that the thorough and consistent collection of objective physiological data is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental driver of accurate patient classification. The previous version of SETS suffered from variability in vital sign measurement and interpretation, leading to inconsistencies. By standardizing this process, the revised scale ensured that triage nurses had clear guidelines for assessing and applying vital sign data, thereby reducing subjective judgment and improving the precision of triage decisions. This demonstrates that for a triage system to be highly effective, it must not only incorporate vital signs but also provide clear, standardized protocols for their measurement and interpretation. The emphasis on standardized vital sign interpretation in the revised SETS, and its demonstrated positive impact on triage accuracy, contrasts with other systems where the specific contribution of vital signs to reliability has not been as thoroughly evaluated. This positions the revised SETS as a model for how objective physiological data, when systematically integrated, can significantly enhance the safety and efficiency of emergency care.

SETS in Practice: Hospital and Pre-hospital Settings

The utility and effectiveness of the Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) extend across various emergency care environments, from the bustling emergency departments to the dynamic pre-hospital setting. Its adaptable design and validated performance have facilitated its widespread adoption and integration into the operational protocols of emergency medical services.

A. Implementation in Emergency Departments

Since its inception in 1997, SETS has been widely adopted by numerous emergency departments in Switzerland, France, and Belgium. This widespread implementation reflects the recognized need for a standardized triage system to manage the increasing patient volumes and ensure appropriate prioritization of care in these settings. In these EDs, all patients admitted are initially triaged by a trained triage nurse using the SETS framework.

A key aspect of SETS implementation and ongoing quality assurance involves the use of interactive computerized simulators. These simulators play a crucial role in both the training of triage nurses and the evaluation of the scale's performance. For instance, studies on the revised SETS utilized such simulators, presenting nurses with clinical scenarios where they could interact by typing questions and receiving replies, including vital signs, before making a triage decision. This simulation environment is designed to mimic real-life triage situations as closely as possible, providing a standardized and controlled method for assessing competency and evaluating the scale's reliability and accuracy. The integration of technology in training and evaluation ensures that nurses are proficient in applying the symptom-based approach and correctly interpreting vital signs, which are central to the revised SETS.

B. Application and Effectiveness in Pre-hospital Care by Paramedics

While triage scales are traditionally validated for hospital emergency departments, the need for effective patient prioritization in the pre-hospital setting is equally critical for optimal patient outcomes and efficient hospital resource utilization. No general emergency department triage scale had been extensively evaluated for pre-hospital use until recent studies involving SETS.

A prospective cross-sectional study specifically evaluated the reliability and performance of SETS when used by paramedics in simulated pre-hospital scenarios. This study involved 23 paramedics evaluating 28 clinical scenarios using interactive computerized triage software, resulting in 644 triage decisions. The findings were highly encouraging: the overall inter-rater reliability for triage level among paramedics was excellent, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.77–0.99). This indicates a high degree of consistency in triage decisions among different paramedics using SETS in the field.

Furthermore, the accuracy of triage decisions made by paramedics was very high, with the correct emergency level assigned in 89% of cases. The rates of mistriage were low, with an overtriage rate of 4.8% and an undertriage rate of 6.2%. These results are particularly noteworthy because they suggest that SETS can be safely and effectively used in the pre-hospital setting by paramedics in Switzerland to determine the level of emergency.

Beyond determining the emergency level, the study also assessed the reliability and accuracy of patient orientation, especially for elderly patients. For the subgroup of simulated patients aged 75 years or older, the ICC for orientation was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.61–0.89), and the correct orientation rate was 93%. This is particularly relevant for guiding patients to the most appropriate hospital, such as a dedicated geriatric emergency center, especially for non-life-threatening conditions. The ability of paramedics to accurately triage and direct patients from the field to the correct facility, based on acuity and suspected diagnosis, represents a significant advancement in pre-hospital patient management. This capability not only optimizes resource allocation within hospitals but also ensures that patients receive care in the most suitable environment from the outset, potentially improving outcomes and reducing burdens on general emergency departments.

C. Training and Competency Development for SETS Users

Effective implementation and consistent application of SETS rely heavily on comprehensive training and ongoing competency development for emergency care professionals. Both nurses and paramedics undergo specific training to ensure proficiency in using the scale.

For emergency department nurses, the standard training for using SETS in some centers involves a 4-hour teaching session. This training is typically provided by certified emergency medicine nurses and emergency physicians specialized in ED triage. After this initial teaching, participants often use SETS in the field for a period, such as two months, to familiarize themselves with the scale, receiving systematic feedback on their triage decisions from principal investigators. This blended approach of didactic instruction and supervised practical experience is crucial for embedding the standardized vital sign measurement and interpretation protocols central to the revised SETS.

Paramedics in Switzerland receive a comprehensive 3-year education program that includes both didactic courses and field internships. This extensive training prepares them for various aspects of emergency medicine, including the application of triage scales like SETS in the pre-hospital environment. The demonstrated excellent reliability and high accuracy of paramedics using SETS, even with minimal additional training for the instrument itself, underscore the effectiveness of their foundational education and the intuitive nature of the revised scale.

Institutions like the Swiss Institute of Emergency Medicine (SIRMED) and the Swiss Center for Rescue, Emergency and Disaster Medicine (SCRED) play vital roles in supporting and advancing emergency medicine education and training in Switzerland. SIRMED, a non-profit organization co-owned by the Swiss Paraplegic Foundation and Swiss Air-Rescue Rega, focuses on enabling emergency care practitioners to provide optimal care through various education and training possibilities for professionals and laypeople. It offers seminars for specialists in emergency services, EDs, intensive care units, and anesthesiology, including courses from internationally recognized institutions. SCRED serves as a platform for strengthening research and advanced education in rescue, emergency, and disaster medicine, promoting consistency in terminology, and developing registries for emergency records. While specific SETS training courses and certification details are not explicitly outlined for SIRMED, their broader mission and offerings strongly align with the continuous professional development required for effective SETS application. The emphasis on ongoing education and systematic feedback mechanisms ensures that users maintain high proficiency, which is essential for the consistent and accurate application of SETS in real-world emergency scenarios.

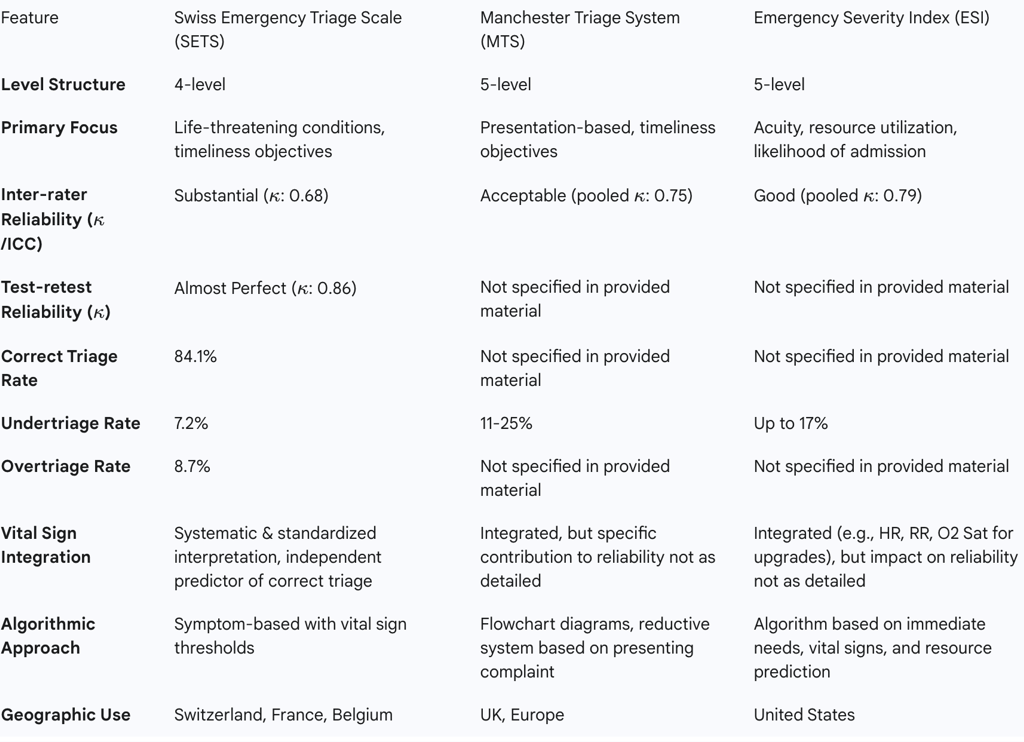

Comparative Analysis: SETS vs. International Triage Systems

The efficacy of the Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) can be further understood by comparing its structure, performance, and underlying principles with other widely adopted international triage systems, particularly the Manchester Triage System (MTS) and the Emergency Severity Index (ESI). These comparisons highlight the unique strengths and operational characteristics of SETS.

A. SETS vs. Manchester Triage System (MTS)

The Manchester Triage System (MTS) is a prominent five-level triage system predominantly used in the UK and European Emergency Departments. It differs structurally from SETS, which is a four-level scale. The MTS categorizes patients into five priority groups: Immediate (Red), Very Urgent (Orange), Urgent (Yellow), Standard (Green), and Non-urgent (Blue), each with an advised maximum waiting time for physician care.

In terms of algorithmic approach, the MTS is presentation-based, utilizing 52 flowchart diagrams that guide nurses through a reductive process based on what the patient states is happening, rather than a definitive diagnosis. This contrasts with SETS's symptom-based approach, which integrates vital sign measurement and interpretation as a core component for attributing emergency levels.

When comparing reliability, the revised SETS demonstrates substantial inter-rater reliability (κ: 0.68) and almost perfect test-retest reliability (κ: 0.86). Meta-analyses of the MTS have shown a pooled κ of 0.75, indicating an acceptable level of overall reliability. While the MTS shows slightly higher pooled inter-rater reliability in some analyses, the revised SETS's performance is still considered "comparable to the best validated triage instruments".

Regarding mistriage rates, the revised SETS has a correct triage rate of 84.1%, with undertriage at 7.2% and overtriage at 8.7%. The MTS has reported undertriage rates ranging from 11% to 25%. This suggests that the revised SETS generally achieves lower rates of undertriage compared to the MTS, which is a critical advantage for patient safety as it minimizes the risk of delayed care for acutely ill patients. The emphasis on standardized vital sign interpretation in SETS may contribute to this lower undertriage rate by providing clearer, objective criteria for escalation.

B. SETS vs. Emergency Severity Index (ESI)

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) is another widely used five-level triage tool, particularly prevalent in emergency departments across the United States. Like the MTS, ESI is a five-level ordinal scale (ESI 1 to ESI 5, from most to least urgent). A key difference in principle is that ESI categorizes patients based on both acuity and predicted resource utilization in the ED, as well as the likelihood of hospital admission. This resource-driven aspect is a notable distinction from SETS, which primarily focuses on life-threatening conditions and timeliness objectives.

In terms of reliability, the ESI's pooled κ has been reported as 0.79 in recent meta-analyses, indicating good reliability. The revised SETS, with its inter-rater κ of 0.68 and test-retest κ of 0.86, demonstrates comparable overall reliability to the ESI.

When comparing mistriage rates, the revised SETS exhibits a correct triage rate of 84.1%, with undertriage at 7.2% and overtriage at 8.7%. The ESI has reported undertriage rates as high as 17%. This again positions the revised SETS favorably with lower rates of undertriage, which is a crucial indicator of patient safety.

Regarding vital sign integration, both SETS and ESI incorporate vital signs. The ESI, for example, integrates heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation to upgrade patients from ESI 3 to 2. However, the study on the revised SETS specifically highlighted that vital sign measurement is a cornerstone of its triage process, with each additional vital sign measured significantly increasing the chance of correct triage. The specific impact of vital sign standardization on ESI's reliability has not been as extensively assessed in published literature as it has for SETS. This suggests that while vital signs are used in both, the explicit emphasis on and demonstrated benefit of

standardized vital sign interpretation is a distinct strength of the revised SETS. The ESI has also been noted to have limitations, including its validation against resource utilization rather than patient outcomes, and a degree of subjectivity in scoring based on nurses' clinical judgment.

C. Key Differentiators and Performance Benchmarks

The comparative analysis reveals several key differentiators that underscore the strengths of the revised SETS within the global landscape of triage systems.

Standardized Vital Sign Interpretation: The most significant differentiator for the revised SETS is its explicit and empirically validated emphasis on standardized vital sign measurement and interpretation. The research clearly demonstrates that this standardization was the direct cause of its improved reliability and reduced mistriage rates. The causal link between standardized objective data collection and enhanced triage accuracy is a powerful testament to the revised SETS's design. This contrasts with other systems where, while vital signs are used, their specific contribution to reliability through standardization has not been as thoroughly evaluated or highlighted as a primary driver of performance improvement.

Lower Undertriage Rates: The revised SETS consistently achieves lower rates of undertriage (7.2%) compared to the MTS (11-25%) and ESI (up to 17%). This is a critical performance benchmark, as undertriage poses the greatest risk to patient safety by delaying care for potentially critical conditions. The ability of SETS to minimize this risk is a substantial advantage.

Four-Level Structure with Timeliness Objectives: While many international systems are five-level, SETS's four-level structure, combined with clear timeliness objectives for each level, provides a concise yet effective framework for prioritization. This potentially simplifies the decision-making process for triage personnel while maintaining clinical rigor.

Proven Effectiveness in Pre-hospital Setting: The validated reliability and accuracy of SETS when used by paramedics in pre-hospital settings is a notable strength. This enables efficient patient diversion to appropriate specialized centers, such as geriatric emergency units, directly from the field, optimizing patient pathways and reducing strain on general EDs.

In summary, the revised SETS benchmarks favorably against "best validated triage instruments" like the MTS and ESI. Its particular strength lies in its demonstrated ability to reduce mistriage, especially undertriage, through a meticulously standardized approach to vital sign assessment. This makes it a highly effective and safe triage tool for both hospital and pre-hospital emergency care.

Table 5: Comparative Overview of SETS, MTS, and ESI

Governance, Quality Assurance, and Future Directions

The sustained effectiveness and widespread acceptance of the Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) are underpinned by robust governance structures and continuous quality assurance processes within the Swiss healthcare system. These mechanisms ensure the scale's consistent application, ongoing relevance, and potential for future adaptation.

A. Role of Swiss Medical Authorities and Professional Societies

The Swiss Society of Emergency and Rescue Medicine (SGNOR) plays a pivotal role in the endorsement and recommendation of SETS. This official backing from a leading professional society signifies the scale's adherence to high clinical standards and its integration into the national emergency medicine framework. The SGNOR, alongside the Interassociation for Rescue Services (IVR) and the Coordinated Medical Services (KSD) of the Swiss Federal Government, is actively involved in initiatives such as developing a registry for emergency records in Switzerland to ensure comprehensive quality control and outcome research in pre-hospital settings. This collaborative approach among professional bodies and governmental agencies highlights a concerted effort to standardize and improve emergency care across the country.

The broader context of the Swiss health system, characterized by its multi-lingual, multi-cultural, and highly decentralized political structure, presents unique challenges for implementing effective interventions and ensuring consistent care delivery. In this complex environment, implementation science—the scientific study of methods to integrate research findings into care delivery—is particularly promising. Organizations like IMPACT, the Swiss Implementation Science Network (founded 2019), and the Institute for Implementation Science in Health Care (IfIS) at the University of Zurich (established 2020) are actively working to bridge the "know-do" gap in healthcare. Their efforts support the translation of scientific knowledge into concrete improvements in practice, which is directly relevant to the ongoing refinement and application of tools like SETS within the Swiss context. The successful implementation of SETS across such a diverse and decentralized system serves as a practical example of how evidence-based practices can be embedded into complex healthcare environments.

B. Quality Assurance and Continuous Improvement

Ensuring the ongoing quality and consistency in SETS application involves several layers of mechanisms, from initial training to systematic feedback and external oversight. As previously discussed, structured training programs for nurses and paramedics, including didactic sessions and supervised field experience with feedback, are fundamental to building and maintaining user competency. This continuous professional development ensures that emergency care providers are proficient in the standardized vital sign measurement and interpretation protocols that are critical to the revised SETS's accuracy.

Beyond individual competency, external bodies contribute to systemic quality assurance. The Swiss Agency of Accreditation and Quality Assurance (AAQ) safeguards and promotes the quality of teaching and research at universities in Switzerland. While its primary focus is academic quality, its role in developing guidelines and quality standards, and conducting accreditation and evaluation procedures, contributes to the broader ecosystem of healthcare quality. Similarly, organizations like SGS provide comprehensive quality control and certification services across various industries, ensuring compliance with statutory and contractual quality requirements. While not specific to SETS, their general expertise in quality control methodologies could inform or support the development of robust auditing and monitoring processes for triage systems within healthcare institutions. The combination of internal training and feedback loops with external quality oversight mechanisms creates a comprehensive framework for ensuring the reliable and consistent application of SETS, thereby contributing to improved patient safety and outcomes.

C. Challenges and Opportunities for Further Development

Despite its proven efficacy, the Swiss Emergency Triage Scale, like any clinical tool, faces ongoing challenges and presents opportunities for further development. One area for continued refinement relates to adapting the scale to evolving emergency care needs and specific patient populations. For instance, while SETS has shown excellent performance in guiding elderly patients to specialized geriatric centers in pre-hospital settings, ongoing research could explore its nuanced application in other specific demographics or clinical presentations.

Opportunities for further development include:

Integration with Digital Health Technologies: Exploring how SETS can be seamlessly integrated with electronic health records and digital triage solutions could further enhance efficiency, data capture, and real-time decision support.

Real-World Outcome Studies: While simulation studies have demonstrated high reliability and accuracy, conducting more extensive real-world outcome studies could provide deeper insights into the long-term impact of SETS on patient morbidity, mortality, and resource utilization across diverse clinical settings.

Adaptation for Mass Casualty Incidents: Investigating how the core principles of SETS could be adapted or integrated into protocols for mass casualty incidents or disaster triage, where rapid and efficient prioritization is paramount.

International Applicability: Further research into the generalizability and adaptability of the revised SETS to other national healthcare systems, particularly those in Europe that currently lack universal triage systems, could facilitate broader adoption and standardization of emergency care practices.

The continuous development of implementation science in Switzerland, with its focus on bridging the gap between research and practice, provides a strong foundation for addressing these challenges and capitalizing on these opportunities. By fostering stronger ties between clinical and implementation researchers and sensitizing healthcare organizations to the importance of quality implementation, the reach of effective interventions like SETS can be further enhanced.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The Swiss Emergency Triage Scale (SETS) has evolved into a highly effective and reliable instrument for prioritizing patient care in emergency medical settings. Its journey from a moderately reliable system with high undertriage rates to a robust, evidence-based tool underscores the critical importance of standardization, particularly in the objective assessment and interpretation of vital signs. The systematic revision of SETS, guided by expert consensus and validated through rigorous simulation studies, has yielded a scale with substantial inter-rater and almost perfect test-retest reliability, coupled with impressively low rates of mistriage.

The proven utility of SETS extends beyond hospital emergency departments into the crucial pre-hospital environment, where paramedics demonstrate high accuracy in patient classification and appropriate destination guidance. This dual applicability highlights SETS as a versatile tool capable of enhancing patient flow and safety across the entire emergency care continuum. When compared to international benchmarks like the Manchester Triage System (MTS) and the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), the revised SETS distinguishes itself with its demonstrated lower undertriage rates and the explicit, empirically supported impact of standardized vital sign interpretation on triage accuracy.

Based on this comprehensive analysis, the following strategic recommendations are put forth for the continued optimization and potential broader adoption of SETS:

Sustain and Enhance Training and Quality Assurance: Continuous investment in standardized training programs for all SETS users, including both nurses and paramedics, is paramount. This should include regular refresher courses, simulation-based training, and systematic feedback mechanisms to ensure ongoing competency and adherence to the standardized vital sign interpretation protocols. The integration of digital tools for training and performance monitoring could further enhance these efforts.

Conduct Real-World Outcome-Based Research: While simulation studies have provided robust validation, further large-scale, prospective studies evaluating the impact of SETS on patient outcomes (e.g., mortality, length of hospital stay, readmission rates) in diverse real-world clinical settings would provide invaluable evidence. Research focusing on specific patient populations, such as those with complex comorbidities or rare conditions, could also refine the scale's application.

Explore Digital Integration and Artificial Intelligence: Investigating the seamless integration of SETS into electronic health record systems and exploring the potential of artificial intelligence and machine learning to support or enhance triage decisions, particularly in data interpretation and predictive analytics, could represent a significant leap forward in efficiency and accuracy.

Facilitate International Knowledge Exchange and Adaptation: Given SETS's demonstrated success, particularly in a European context where universal triage systems are less common, actively sharing its methodology and implementation experience with other countries could foster broader adoption of standardized emergency care practices. This could involve developing adaptable frameworks for SETS implementation that account for varying healthcare system structures and cultural contexts.

Promote Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Continued collaboration among emergency medicine physicians, nurses, paramedics, and implementation scientists is essential for identifying new challenges, refining the scale, and ensuring its responsiveness to evolving healthcare needs and technological advancements. This interdisciplinary approach will ensure that SETS remains at the forefront of emergency triage methodology.