The Japan Triage and Acuity Scale (JTAS)

The Japan Triage and Acuity Scale (JTAS) represents a pivotal advancement in the standardization of emergency medical care in Japan. Developed in 2012 by the Japanese Society for Emergency Medicine (JSEM) and the Japanese Association for Emergency Nursing (JAEN).

The Japan Triage and Acuity Scale (JTAS) represents a pivotal advancement in the standardization of emergency medical care in Japan. Developed in 2012 by the Japanese Society for Emergency Medicine (JSEM) and the Japanese Association for Emergency Nursing (JAEN), JTAS is a direct adaptation of the highly validated Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS). Its implementation aimed to replace disparate, informal triage methods with a unified, five-level acuity system to prioritize patients, optimize resource allocation, and improve the efficiency of care in increasingly overcrowded Emergency Departments (EDs).

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the JTAS, examining its origins, structural framework, clinical performance, and position within the global landscape of emergency triage. A key evolution of the system is the development of the modified JTAS (mJTAS), a pragmatic adaptation designed to address specific challenges within the Japanese healthcare environment. The mJTAS shifts the triage focus from a single chief complaint—a model that proved challenging for Japan's large elderly population with multiple comorbidities—to a system based on eight objective physiological and situational domains. This modification, along with the removal of a web-connectivity requirement to comply with data privacy regulations, marks a significant philosophical and practical divergence from the parent CTAS model.

Empirical studies have robustly validated the predictive capabilities of JTAS. There is a strong, statistically significant correlation between higher JTAS acuity levels and critical clinical outcomes, including increased rates of hospital and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, as well as longer ED lengths of stay. The introduction of JTAS has also been shown to improve operational efficiency by reducing triage times and enhancing inter-rater reliability between nurses and physicians compared to previous unstructured systems.

Despite these successes, the JTAS is subject to significant and critical limitations that temper its overall effectiveness. The most pressing concern is a demonstrated pattern of undertriage, where a substantial percentage of patients requiring ICU-level care are assigned to lower-acuity triage levels, posing a considerable risk to patient safety. Furthermore, the criteria for the lowest acuity level (Level 5, Non-urgency) are poorly defined, leading to its underutilization and a subsequent reduction in the scale's ability to discriminate between non-urgent cases. Like its CTAS-based counterparts, JTAS also exhibits diminished performance in geriatric patients, a critical issue for Japan's super-aged society.

The future of JTAS and emergency triage in Japan hinges on addressing these deficiencies. This will require strategic revisions to the official guidelines, particularly to clarify low-acuity criteria and enhance sensitivity to prevent undertriage. The integration of technology, including artificial intelligence and digital health platforms, offers promising avenues for improving triage accuracy and efficiency. Ultimately, the evolution of JTAS must be guided by the profound demographic reality of Japan, necessitating the development of geriatric-specific modifiers and a systemic adaptation to the complex needs of an aging population.

The Genesis and Architectural Framework of the Japan Triage and Acuity Scale

The Imperative for a Standardized Triage System in Japan

The global phenomenon of Emergency Department (ED) overcrowding is a critical challenge to modern healthcare systems, creating an environment where the demand for immediate care frequently outstrips available resources. In this context, triage—the process of sorting patients to establish the priority of their treatment based on clinical urgency—is not merely an administrative task but a cornerstone of safe and effective emergency medical care. A standardized and validated triage system ensures that patients are treated in order of their clinical need rather than their time of arrival, thereby optimizing the allocation of medical personnel, diagnostic tools, and treatment spaces to maximize patient outcomes.

Prior to the introduction of a national standard, the landscape of emergency triage in Japan was fragmented. Many EDs relied on their own institutional, often informal, triage scales or simple systems based on clinical experience. This lack of standardization led to inconsistencies in patient prioritization across facilities and created difficulties in benchmarking quality of care and patient flow on a regional or national level. Furthermore, the concept of ED triage had not become common practice, partly due to a cultural connotation in Japan that associated the term "triage" primarily with mass-casualty disaster scenarios rather than routine hospital operations. Recognizing the need for a unified, evidence-based approach to manage rising patient volumes and ensure equitable care, Japanese medical societies sought to adopt an internationally recognized framework.

From Canada to Japan: The Adaptation of CTAS and the Role of the JSEM

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), developed in the 1990s by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP), was identified as an ideal foundational model for Japan. CTAS is a well-established, web-based triage system that has demonstrated high validity and reliability in numerous international studies, making it one of the most widely accepted triage tools globally. Its structured approach, combining a comprehensive list of patient complaints with physiological modifiers, provided a robust framework for adaptation.

The development and implementation of a Japanese version was a collaborative effort led by the country's foremost emergency medicine organizations. The Japanese Society for Emergency Medicine (JSEM) and the Japanese Association for Emergency Nursing (JAEN) jointly spearheaded the project. After a period of development that included the release of a prototype in 2011 , the official translated and adapted system, named the Japan Triage and Acuity Scale (JTAS), was formally implemented in Japanese EDs in April 2012. The fundamental principles of JTAS are directly based on CTAS, though the adaptation process involved incorporating certain conditions more commonly seen in Japan, such as heat stroke, to ensure clinical relevance. Japan became a formal "franchise partner" of the CTAS National Working Group, enabling a structured process for translation, modification, and educational support, with the Japanese government supporting its implementation and the development of a national database.

The Five-Level Acuity Structure: Core Principles and Clinical Application

Inheriting its architecture directly from CTAS, the JTAS is a five-level acuity scale designed to classify patients based on the severity of their condition and the urgency with which they require physician assessment. The five levels are standardized across all CTAS-based systems and are defined as follows :

Level 1: Resuscitation: Conditions that are immediately life-threatening and require immediate, simultaneous assessment and treatment.

Level 2: Emergency: Conditions that are a potential threat to life, limb, or function, requiring rapid medical intervention.

Level 3: Urgency (or Semi-emergency): Conditions that could potentially progress to a serious problem requiring emergency intervention. These patients are associated with significant discomfort or affect their ability to function at work or home.

Level 4: Low Urgency (or Less Urgent): Conditions that, based on patient history and vital signs, are not acute but may require intervention or reassurance within one to two hours.

Level 5: Non-urgency: Conditions that are non-urgent and could be acute but minor or part of a chronic problem.

The clinical application of the original JTAS follows a structured, complaint-driven process. The triage nurse begins by identifying the patient's single most significant complaint from a comprehensive list containing 17 main complaint groups and 165 specific complaints. Following this, the nurse applies a series of modifiers to adjust the acuity level.

First-order modifiers are critical physiological signs that can override the complaint-based level, such as abnormal vital signs (respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, heart rate), level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale), and severe pain.

Second-order modifiers are specific to certain complaints and help refine the triage decision. The final JTAS level is determined by the highest level of acuity indicated by either the chief complaint or the modifiers.

The Modified JTAS (mJTAS): A Pragmatic Evolution for the Japanese Clinical Environment

Soon after its introduction, practical challenges with the original JTAS model became apparent in the unique clinical and regulatory context of Japan. These challenges prompted the development of the modified Japanese Triage and Acuity Scale (mJTAS), a significant evolution of the system designed for greater efficiency and applicability. The mJTAS was created by focusing on the original JTAS first-order modifiers while fundamentally altering the initial triage process.

The development of the mJTAS was driven by two primary limitations of the parent system:

The Single Chief Complaint Requirement: The mandate to identify a single chief complaint proved to be a significant bottleneck, particularly when triaging elderly patients. In Japan's super-aged society, a large proportion of ED patients are older adults who often present with multiple comorbidities, vague symptoms, or several concurrent complaints. Forcing a triage nurse to distill these complex presentations into a single complaint was often impractical, time-consuming, and could lead to an inaccurate representation of the patient's overall condition.

The Web Connectivity Requirement: The original CTAS/JTAS framework was designed as a web-based tool. However, strict government guidelines in Japan regarding the protection and handling of personal information placed significant limitations on web connectivity in the healthcare environment. This regulatory hurdle made a system that could function offline a practical necessity for many Japanese institutions.

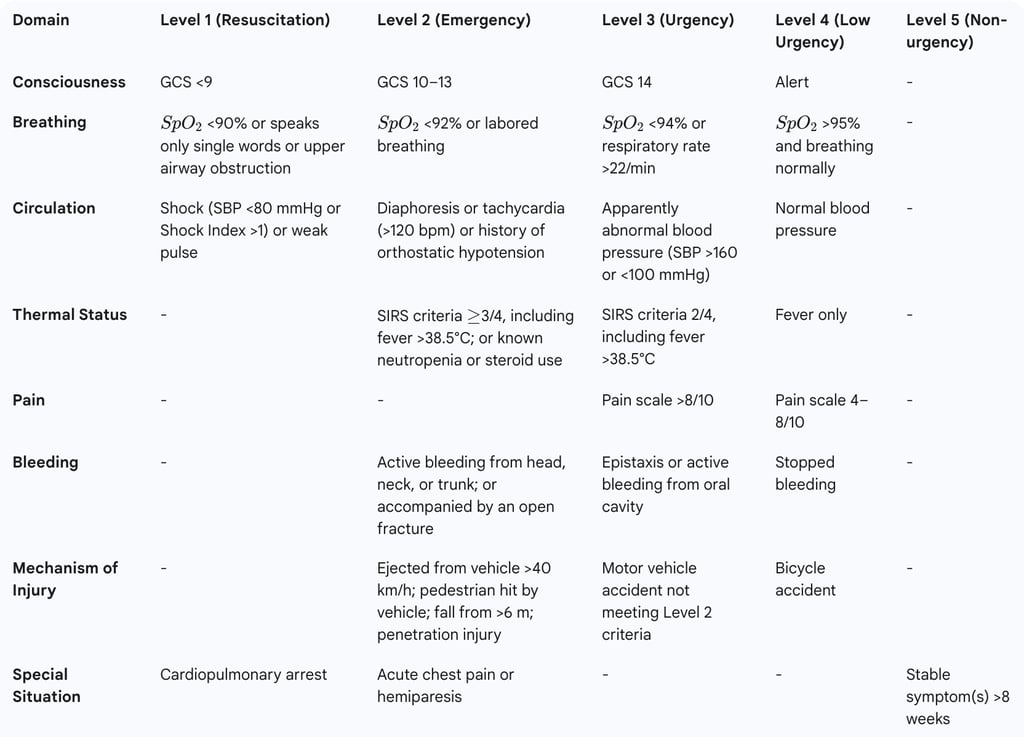

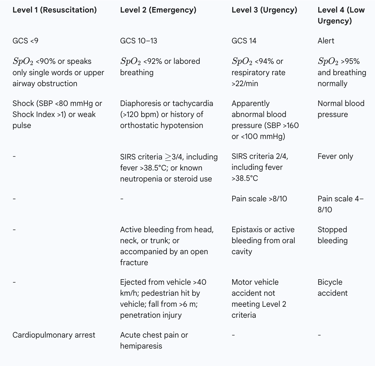

The mJTAS addresses these issues by shifting the triage paradigm from a complaint-based to a physiologically-based assessment. Instead of starting with a chief complaint, the mJTAS process is built on the rapid evaluation of eight objective domains, as detailed in Table 1. The triage nurse assesses each domain and assigns the final acuity level based on the single domain with the most urgent finding. This approach allows for a more direct and rapid assessment of a patient's clinical state, bypassing the complexities of interpreting multiple subjective complaints.

A crucial clinical safeguard was built into the mJTAS: patients presenting with acute chest pain or hemiparesis are automatically assigned to Level 2 (Emergency) or higher, regardless of their vital signs. This exception acknowledges that time-critical conditions such as myocardial infarction or cerebral hemorrhage require immediate intervention and may not initially present with grossly abnormal physiological parameters. This modification reflects a pragmatic understanding of high-risk clinical presentations. The resulting system is a streamlined, offline-capable tool that prioritizes objective data, making it better suited to the demographic and regulatory realities of emergency medicine in Japan.

Table 1: The Architectural Framework of the Modified JTAS (mJTAS) This table outlines the clinical descriptors used to determine the triage level across eight objective domains. The final acuity level is assigned based on the domain with the most severe finding.

Source: Adapted from Funakoshi H, et al. (2016). GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale;

SpO2: Oxygen Saturation; SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure; SIRS: Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome.

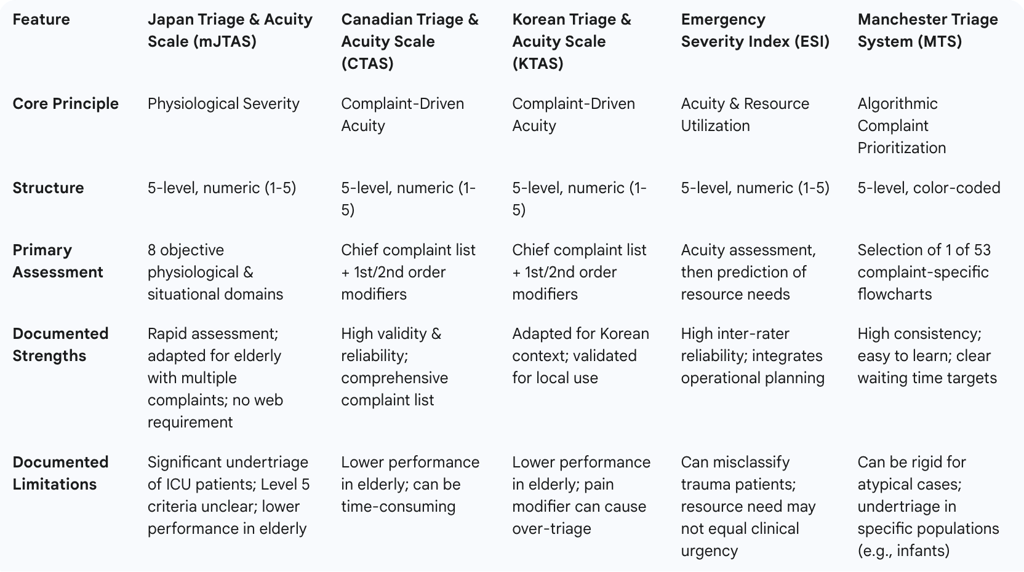

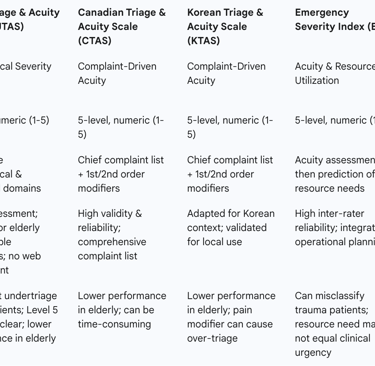

A Comparative Analysis of Global Triage Methodologies

Understanding the Japan Triage and Acuity Scale requires situating it within the broader international context of emergency triage. Its development, strengths, and weaknesses are best understood by comparing it to its direct progenitor (CTAS), its closest regional counterpart (KTAS), and other globally prominent systems like the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) and the Manchester Triage System (MTS). Each system operates on a distinct philosophical basis, optimizing for different primary goals such as clinical acuity, resource management, or procedural consistency.

JTAS and its Progenitor: A Deep Dive into the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS)

The JTAS is fundamentally a Japanese iteration of the CTAS. Both systems share the same core architecture: a five-level acuity scale ranging from Level 1 (Resuscitation) to Level 5 (Non-Urgent), a comprehensive list of presenting complaints, and the use of first-order (physiological) and second-order (symptom-specific) modifiers to determine the final triage level. The triage process in both original systems is complaint-driven, requiring the nurse to first select a presenting complaint before applying modifiers.

The divergence between the systems is most evident in the development of the mJTAS. As previously detailed, the mJTAS was specifically designed to overcome challenges encountered when applying the CTAS model in Japan. The shift away from a mandatory chief complaint and toward a direct assessment of physiological domains represents the most significant modification, tailoring the system to a patient population with a high prevalence of elderly individuals with complex comorbidities. The second key difference is the move to an offline system to comply with Japan's stringent data privacy laws, a practical adaptation not required in the Canadian context.

The relationship between the two systems is not static but collaborative. The CTAS guidelines undergo periodic revisions, and these updates sometimes incorporate learnings from international partners. For example, the addition of a "heat related issue" complaint to the CTAS was influenced by its prior inclusion in the JTAS, reflecting the clinical realities of the Japanese climate. Similarly, the 2016 CTAS revision introduced a "frailty modifier," a concept highly relevant to the challenges faced in Japan and a potential model for future JTAS updates.

Regional Counterparts: Structural and Philosophical Parallels with the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS)

The Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS) is the closest regional and structural analogue to the JTAS. Like JTAS, KTAS was developed in 2012 based on the CTAS framework and was implemented nationwide in South Korea in 2016. Both are five-level, symptom-oriented triage scales that utilize a similar process of identifying a patient's complaint and applying primary and secondary modifiers (such as vital signs, pain score, and mechanism of injury) to determine the final acuity level.

The development process for KTAS involved a formal Delphi method to gather consensus from Korean emergency medicine experts, ensuring the modifications were systematically tailored to the nation's specific medical situation. This structured adaptation process aimed to reduce errors that might arise from a simple translation of the CTAS guidelines.

A critical parallel between the two systems lies in a shared limitation. Independent studies conducted in both Japan and South Korea have concluded that the respective triage scales exhibit lower predictive performance and discriminative ability in elderly patients compared to the general adult population. This recurring finding suggests an inherent challenge within the foundational CTAS model when applied to the demographic realities of super-aged societies, where atypical presentations and multiple comorbidities are common. This shared weakness underscores the need for ongoing, region-specific research and the potential development of geriatric-focused modifiers in both JTAS and KTAS.

Global Benchmarking: Juxtaposing JTAS with the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) and the Manchester Triage System (MTS)

While JTAS and KTAS represent adaptations of the CTAS model, the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) and the Manchester Triage System (MTS) are built on different core principles.

JTAS vs. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): The ESI, widely used in the United States, is also a five-level triage system. However, its methodology diverges significantly from JTAS. The initial assessment in ESI focuses on identifying high-acuity patients (Level 1 and 2) who require immediate life-saving intervention or are in a high-risk situation. For the remaining patients, the ESI algorithm pivots to a question of anticipated resource utilization: "How many resources will this patient likely need?". A patient expected to need two or more resources is typically assigned Level 3, one resource is Level 4, and no resources is Level 5. This makes ESI a hybrid system that combines clinical acuity with operational forecasting. A direct comparative study involving JTAS-trained nurses in Japan using simulated scenarios found that ESI demonstrated a higher degree of inter-rater reliability (weighted kappa k=0.82) compared to JTAS (k=0.74), suggesting that the ESI's structure may lead to more consistent triage decisions, even within the Japanese healthcare setting.

JTAS vs. Manchester Triage System (MTS): The MTS, developed in the United Kingdom, is the most algorithmic and protocol-driven of the major triage systems. It operates using 53 distinct, complaint-specific flowcharts. The triage nurse selects the appropriate flowchart based on the patient's chief complaint (e.g., "Chest Pain," "Headache") and follows a series of yes/no questions related to specific discriminators. This process leads directly to one of five color-coded urgency levels (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue), each with a mandated maximum waiting time for physician assessment. The MTS's strength lies in its high degree of standardization, which minimizes subjective clinical judgment. This contrasts with the JTAS/CTAS model, which provides a framework of complaints and modifiers but allows for more flexibility and clinical discretion in their application.

The existence of these different models highlights a fundamental divergence in triage philosophy. The MTS prioritizes consistency through rigid algorithms. The ESI prioritizes operational management by forecasting resource needs. The original JTAS, like CTAS, occupies a middle ground, focusing on clinical acuity through a complaint-based framework with flexible modifiers. The evolved mJTAS carves a unique niche, moving away from complaints altogether to become a purely physiologically-based system, designed for rapid severity assessment in a specific demographic context.

Table 2: Comparative Matrix of International Triage Systems This table provides a high-level comparison of the core principles, structures, and methodologies of five major international emergency triage systems.

Empirical Validation and Clinical Performance of JTAS

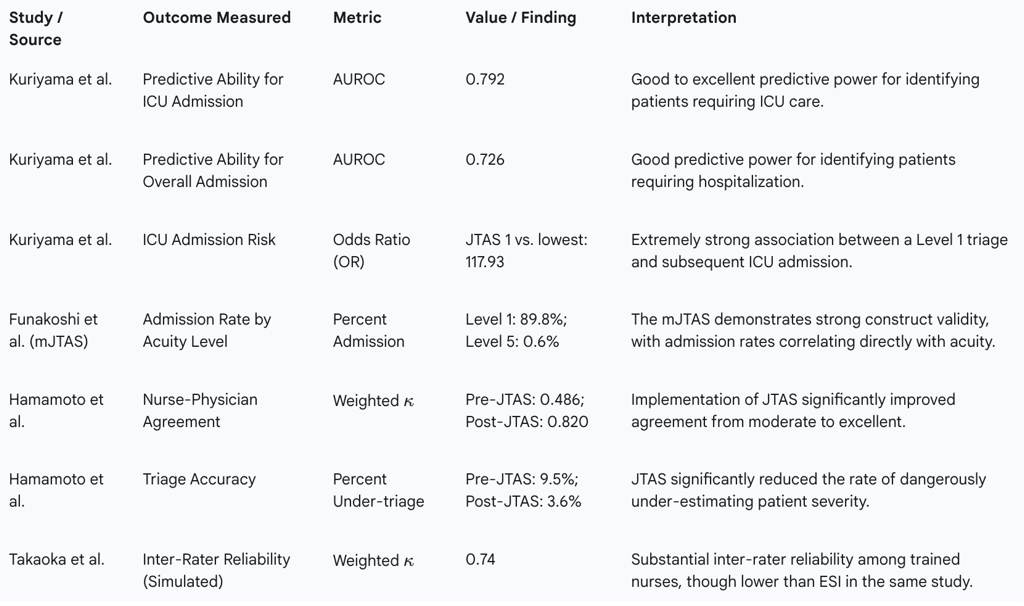

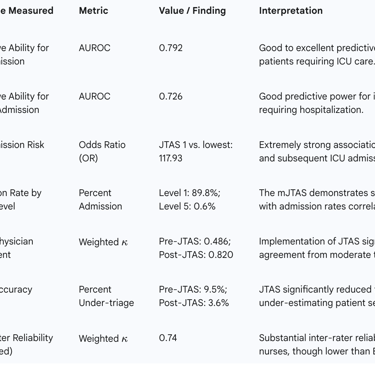

The credibility of any triage system rests on its demonstrated ability to accurately stratify patients and positively impact clinical and operational outcomes. Since its implementation, the JTAS has been the subject of several validation studies in Japan. This body of research has consistently demonstrated the system's predictive validity, showing a strong correlation between assigned triage levels and key indicators of patient severity and resource consumption. Furthermore, its introduction has been linked to significant improvements in ED efficiency and triage accuracy when compared to less structured methods.

Assessing Predictive Validity: Linkages to Hospital Admission, ICU Care, and Mortality

A cornerstone of triage system validation is establishing its ability to predict which patients will require significant medical intervention. A large-scale retrospective cohort study involving 27,120 adult patients provided robust evidence for the predictive validity of JTAS. The study's findings clearly linked higher JTAS acuity levels with more severe clinical outcomes:

Overall Hospital Admission: The odds ratio (OR) for hospital admission was significantly greater for patients assigned to higher triage levels (i.e., lower numerical scores) compared to those at the lowest urgency levels.

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Admission: The association was even more pronounced for ICU admissions. Compared to the lowest urgency levels, the OR for ICU admission was 117.93 (95% CI 69.07 to 201.38) for patients triaged as JTAS Level 1 and 9.43 (95% CI 13.74 to 29.30) for those at JTAS Level 2. This demonstrates the system's strong ability to identify the most critically ill patients.

Predictive Ability: The study used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to quantify the scale's predictive power. The area under the curve (AUROC) for predicting overall hospital admission was 0.726, and for predicting ICU admission, it was 0.792. These values indicate a good to excellent ability to discriminate between patients who will and will not require admission.

Similar validation was conducted for the modified JTAS (mJTAS), which relies on physiological domains rather than chief complaints. This version also demonstrated strong construct validity, with total admission rates showing a clear, progressive increase with acuity: 0.6% for Level 5, 6.6% for Level 4, 26.4% for Level 3, 68.2% for Level 2, and 89.8% for Level 1. This confirms that even after its significant modification, the scale retains its ability to effectively stratify patients by severity.

Impact on Emergency Department Throughput and Operational Efficiency

Beyond clinical prediction, a successful triage system must also enhance the operational efficiency of the ED. Studies comparing performance before and after the implementation of JTAS have shown marked improvements in patient flow. One key time-series study conducted across seven emergency facilities found that the introduction of JTAS led to statistically significant reductions in several critical time intervals (p<0.001) :

Time from registration to triage was shortened by 3.8 minutes.

Triage duration itself was shortened by 1 minute.

Time from registration to physician assessment was shortened by 11.2 minutes.

Patients' perceived waiting time was reduced by 18.6 minutes.

These findings suggest that the structured framework of JTAS allows nurses to make faster, more efficient decisions, leading to expedited patient flow through the initial stages of an ED visit. Furthermore, the validation studies consistently show that higher JTAS levels are associated with significantly longer total ED lengths of stay, which is an expected outcome, as more acute patients naturally require more extensive diagnostic workups and treatments before a disposition decision can be made.

However, the impact is not universally positive across all clinical scenarios. One study noted that while JTAS improved the time to medical attention for acute coronary syndrome patients with clear ST elevation on their initial electrocardiogram, it did not significantly shorten the overall door-to-balloon time or the time to attention for patients without ST elevation. This indicates that while JTAS improves initial processing, its effects on specific, time-critical care pathways may be more limited.

Studies on Inter-Rater Reliability and Triage Accuracy

A critical measure of a triage scale's utility is its reliability—the degree to which different users will assign the same score to the same patient. The introduction of JTAS has led to a dramatic improvement in this area. The same time-series study found that the level of agreement on patient urgency between triage nurses and emergency physicians increased significantly after JTAS implementation. The weighted kappa coefficient (κ), a statistical measure of inter-rater agreement, rose from 0.486 (considered moderate agreement) in the pre-JTAS period to 0.820 (excellent agreement) post-implementation.

This enhanced consistency translated directly into improved triage accuracy. The rate of over-triage (assigning a patient a higher acuity level than necessary) fell from 24.7% to 8.6%, while the rate of under-triage (assigning a lower acuity level than necessary) decreased from 9.5% to just 3.6%. This demonstrates that the structured, criteria-based approach of JTAS provides a common language and framework that reduces ambiguity and leads to more accurate and reproducible triage decisions than informal methods.

Table 3: Synthesis of JTAS Validation Study Outcomes This table summarizes key quantitative findings from major studies evaluating the validity, reliability, and performance of the Japan Triage and Acuity Scale.

Implementation, Challenges, and Critical Appraisals

Despite its demonstrated validity and the official endorsement from major medical societies, the implementation and real-world performance of the JTAS are not without significant challenges. The available literature points to a complex adoption landscape, critical clinical limitations related to patient safety, and systemic issues inherent in the scale's design. These critiques are essential for a balanced understanding of JTAS's role in Japanese emergency medicine.

National Adoption and Prevalence in Japanese Emergency Departments

There is a notable ambiguity in the research regarding the extent of JTAS implementation across Japan. Several studies describe the system as being "implemented in many Japanese EDs" and "used nationwide". This language suggests a broad and successful rollout, positioning JTAS as the de facto national standard.

However, this portrayal is contradicted by other research, which states that JTAS "has not yet been widely adopted" and that a significant number of emergency departments continue to utilize their own proprietary or informal triage scales. This discrepancy points toward a significant gap between policy and practice. The term "nationwide" likely refers to JTAS's official status as the endorsed national guideline developed by JSEM and JAEN. It represents the national standard in principle. The reports of limited adoption, however, likely reflect the practical realities on the ground. Implementing a new, structured triage system requires substantial investment in training, resources, and institutional cultural change. This process can be slow, especially in smaller, non-academic, or secondary-level emergency facilities. The result is likely a fragmented implementation landscape where major tertiary and academic medical centers have adopted JTAS, while a considerable number of other hospitals have not. The lack of definitive national survey data on implementation rates makes it difficult to precisely quantify its prevalence, but the evidence suggests that its use is far from universal.

The Critical Challenge of Undertriage: An Analysis of Misclassification in High-Acuity Patients

Perhaps the most serious criticism leveled against the JTAS concerns patient safety, specifically the risk of undertriage. Undertriage occurs when a patient with a high-acuity condition is erroneously assigned a lower-acuity triage level, potentially leading to delays in assessment and treatment that can result in adverse outcomes. While validation studies confirm that JTAS is effective at a population level—meaning a patient triaged to Level 1 is very likely to be critically ill—a critical analysis reveals that the inverse is not reliably true.

A letter published in the Emergency Medicine Journal in response to the main JTAS validation study highlighted a deeply concerning finding within the study's own data: a substantial proportion of patients who were ultimately admitted to the ICU had been assigned to lower-acuity levels at triage. The specific figures are stark:

44.6% of all ICU patients had been assigned to JTAS Level 3 (Urgency).

12% of all ICU patients had been assigned to JTAS Levels 4 and 5 (Low or Non-urgency).

This means that over half of the patients who were critically ill enough to require intensive care were not identified as high-acuity (Level 1 or 2) at their initial triage assessment. This level of undertriage represents a significant clinical risk and points to a potential weakness in the sensitivity of the JTAS modifiers to detect all forms of physiological distress, particularly in patients who may present without overt signs of instability. This paradox—where the system is statistically valid in predicting outcomes for those it correctly identifies as high-risk, yet simultaneously fails to identify a large portion of that same high-risk group—is the most significant clinical limitation of JTAS and a primary target for future guideline revisions.

Systemic Limitations: Ambiguity in Low-Acuity Criteria and Performance in Geriatric Populations

Beyond the critical issue of undertriage, JTAS faces other systemic limitations inherent in its design.

Ambiguity and Underutilization of Level 5: Multiple analyses have pointed out that the criteria for JTAS Level 5 (Non-urgency) are poorly defined and unclear to triage nurses. As a result, this category is often ignored or underutilized. One study reported that only 1% of patients were triaged to Level 5, in stark contrast to the 44.7% assigned to Level 4. This effectively collapses the lower end of the five-level scale into a single, overcrowded category (Level 4), diminishing the system's ability to discriminate between patients with minor issues and those with slightly more pressing, but still low-acuity, needs. This has led to direct calls from researchers for the JTAS guidelines to be revised to provide a clearer, more functional definition for Level 5 criteria.

Diminished Performance in Geriatric Populations: As Japan's society continues to age at a rapid pace, the performance of its medical systems in the elderly population is of paramount importance. Research has shown that the discriminative ability of JTAS diminishes as patient age increases. This decline is primarily attributed to a drop in specificity, meaning the system is less able to correctly identify elderly patients who are

not high-acuity, leading to an overall increase in misclassification. This is a known issue with other CTAS-based systems like KTAS as well, suggesting a foundational challenge in applying this triage model to older adults who often present with atypical symptoms, multiple comorbidities, and baseline physiological states that differ from younger populations.

Operational Hurdles: From Data Connectivity to Managing Patients with Comorbidities

The operational challenges that spurred the creation of the mJTAS remain relevant critiques of the original CTAS/JTAS methodology. The difficulty of applying the "single chief complaint" rule in a clinical environment dominated by elderly patients with complex medical histories highlights a mismatch between the triage model and the patient demographic. Similarly, the barrier posed by the web-connectivity requirement due to national data privacy laws illustrates the importance of adapting international medical systems to local regulatory frameworks. While the mJTAS was developed as a solution to these specific hurdles, they underscore the fact that even highly validated international systems cannot be implemented without careful consideration of local clinical and administrative contexts.

The Future Trajectory of Emergency Triage in Japan

The continued evolution of the Japan Triage and Acuity Scale and the broader practice of emergency triage in Japan will be shaped by three dominant forces: the need to address the system's documented limitations through guideline revision, the transformative potential of new technologies, and the overwhelming demographic imperative of a super-aged society. The future of JTAS lies in its capacity to adapt to these clinical, technological, and societal pressures.

Strategic Recommendations for the Revision of JTAS Guidelines

The existing body of research provides a clear mandate for the strategic revision of the JTAS guidelines. The primary goal of any future update must be to improve the discrimination of ED patients and enhance patient safety. Two areas require immediate attention:

Clarification of Level 5 Criteria: There is a consensus among critics that the criteria for Level 5 (Non-urgency) must be revised to be more clearly defined and clinically useful. A more functional definition would encourage its proper use by triage nurses, allowing for better differentiation between Level 4 and Level 5 patients. This would restore the full functionality of the five-level scale at the lower-acuity end, improving patient flow and resource allocation for non-urgent cases.

Addressing Systemic Undertriage: The most critical task for future revisions is to address the high rate of undertriage for critically ill patients. The fact that over half of ICU patients are being assigned to mid- or low-acuity levels is a major patient safety concern that must be rectified. This will likely require a deep analysis of undertriaged cases to identify common patterns or missed clinical indicators. Revisions may involve adding new first-order modifiers, refining existing physiological thresholds, or developing specific protocols for high-risk presentations that are currently being missed.

The Integration of Technology: AI, Machine Learning, and Digital Health Platforms

The future of emergency medicine in Japan is inextricably linked with digital health innovation, and triage is a prime area for technological enhancement. Several initiatives are already underway that complement or could be integrated with the JTAS framework:

Public Helplines and Smartphone Applications: Japan has implemented telephone triage services, such as the #7119 public helpline, and smartphone apps for the public. These tools help assess urgency before a patient arrives at the ED, potentially reducing unnecessary ambulance use and directing patients to the most appropriate level of care.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning: There is a growing global interest in using AI and machine learning to support clinical decision-making in triage. In Japan, where the AI healthcare start-up scene is burgeoning, these technologies could be integrated into future versions of JTAS. An AI-powered system could analyze complex combinations of vital signs, demographic data, and chief complaints in real-time to provide a risk score or a recommended triage level, acting as a powerful decision-support tool for nurses and potentially improving the accuracy of risk stratification. The development of new triage methods based on risk ratio calculations and machine learning is already being explored in Japanese hospitals.

Adapting Triage for a Super-Aged Society: The Need for Geriatric-Specific Modifiers

Given Japan's status as the world's most aged society, the single greatest challenge for JTAS is to improve its performance in the elderly population. The documented decline in the system's discriminative ability with increasing patient age necessitates a focused effort to make the scale more sensitive to the unique physiology and clinical presentations of older adults.

A promising path forward can be found in the evolution of JTAS's parent system, the CTAS. The 2016 revisions to the CTAS guidelines introduced a new "frailty modifier". This modifier was specifically designed to help triage nurses identify frail or vulnerable older patients who might be at higher risk of deterioration despite not meeting standard high-acuity criteria. Its application allows for these patients to be up-triaged to a higher level (e.g., CTAS Level 3), ensuring they receive more timely physician assessment and are not left in waiting rooms for extended periods. Adopting or developing a similar frailty or geriatric-specific modifier for JTAS would be a crucial, evidence-based step toward adapting the system to the primary demographic it serves.

Toward a National and Global Standard for Triage

The long-term vision for JTAS involves its use not just as a clinical tool within individual hospitals, but as a source of national data for healthcare planning and quality improvement. Efforts are underway to promote nationwide data collection and analysis from institutions using JTAS. This would allow for the creation of regional and national benchmarks, enabling comparisons of ED performance and the evaluation of regional medical functions. This data-driven approach is essential for the continuous refinement of the emergency medical system.

On a broader scale, the challenges faced by JTAS are part of a global conversation about the future of triage. Experts are calling for a more unified, collaborative international approach to address the common weaknesses found in all major triage systems, such as the lack of a universal gold standard for validation and the difficulty in stratifying certain high-risk conditions. By contributing its data and experience, particularly regarding triage in a super-aged population, Japan and the JTAS can play a significant role in the development of future global triage guidelines.

Conclusion

The Japan Triage and Acuity Scale (JTAS), and particularly its pragmatic evolution into the modified JTAS (mJTAS), represents a landmark achievement in the standardization of emergency care in Japan. By adapting the robust, internationally recognized framework of the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, Japan has equipped its Emergency Departments with a tool that has demonstrably improved operational efficiency, enhanced the accuracy and reliability of triage decisions, and shown strong predictive validity for critical patient outcomes such as hospitalization and ICU admission. The mJTAS, with its innovative shift from a complaint-based to a physiologically-driven assessment, stands as a noteworthy example of adapting a global standard to meet local demographic and regulatory needs.

However, the system's successes must be viewed alongside its significant and pressing limitations. The high rate of undertriage for critically ill patients is a serious patient safety concern that challenges the system's core function of identifying those most in need of immediate care. This, combined with poorly defined criteria for low-acuity patients and diminished performance in the rapidly growing geriatric population, indicates that the JTAS is a system in need of further refinement.

The path forward for emergency triage in Japan is clear. It requires a commitment to data-driven, iterative improvement of the JTAS guidelines to address these known weaknesses. It involves embracing technological innovation, such as artificial intelligence and digital health platforms, to augment the decision-making capabilities of triage nurses. Most importantly, it demands a dedicated focus on adapting the triage process to the complex realities of a super-aged society, likely through the development of geriatric-specific tools and modifiers. By confronting these challenges directly, the Japanese emergency medical community can build upon the solid foundation of the JTAS to create a more resilient, accurate, and safe triage system for the future.