The German Emergency Severity Index (ESI-D)

While ESI-D has proven effective, the German emergency care landscape also features the widespread use of the Manchester Triage System (MTS). A comparative analysis reveals distinct algorithmic designs and performance characteristics, with ESI-D often showing superior predictive power

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) stands as a foundational five-level triage algorithm, pivotal in modern emergency department operations. Its adaptation and implementation within the German healthcare system, often implicitly referred to as ESI-D, represents a significant stride towards standardizing patient prioritization. This system categorizes patients based on the acuity of their medical condition and the anticipated number of resources required for their care, a unique dual approach that distinguishes it from other triage models. Extensive validation studies in Germany have demonstrated its high reliability and validity, affirming its capacity to consistently identify patients requiring urgent intervention and to predict outcomes such as hospitalization and intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

The adoption of ESI-D has demonstrably influenced patient flow, contributing to reduced length of stay in emergency departments and facilitating more strategic resource allocation. It plays a crucial role in enhancing patient safety by ensuring that critically ill individuals receive timely care, particularly in crowded environments. While ESI-D has proven effective, the German emergency care landscape also features the widespread use of the Manchester Triage System (MTS). A comparative analysis reveals distinct algorithmic designs and performance characteristics, with ESI-D often showing superior predictive power for hospitalization, though it may exhibit higher overtriage rates in some contexts. The continued co-existence of these systems underscores the multifaceted considerations influencing their adoption.

Despite its successes, challenges persist, including the ongoing issue of emergency department overcrowding and the complexities of triage for specific patient populations, such as pediatrics and geriatrics. The report concludes with recommendations for sustained investment in comprehensive training, rigorous quality assurance, and robust interprofessional collaboration to further optimize ESI-D's potential. Continuous research and adaptation are essential to address evolving healthcare demands and to integrate advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence, into future triage practices.

Introduction to Emergency Department Triage in Germany

1.1. The Imperative of Structured Triage in Modern Emergency Medicine

Modern emergency departments (EDs) worldwide face increasing pressure due to the unpredictable arrival of patients and a growing demand for medical services that often exceeds available capacity. This imbalance poses a significant threat to patient safety and the overall quality of healthcare delivery. In response, structured triage systems have become indispensable tools for managing patient flow and ensuring that individuals receive appropriate care in a timely manner.

Triage, in the context of emergency medicine, refers to the primary assessment of patients presenting with acute health disorders, initially deemed medical emergencies. Its fundamental purpose is to rapidly sort patients, assign treatment priorities based on the severity of their condition, and direct them to the most suitable treatment area. This process is particularly critical when a large number of patients arrive simultaneously, as effective triage enables the quick identification of those in emergency and time-sensitive conditions, thereby preventing delays that could compromise patient outcomes. The transition from informal, ad-hoc patient assessment to formalized, structured triage systems reflects a maturation of emergency medicine as a discipline. This evolution is driven by the dual imperatives of enhancing patient safety and optimizing operational efficiency in increasingly crowded ED environments. The adoption of such systems seeks to ensure reproducibility and clinical relevance in initial patient stratification.

1.2. Landscape of Triage Systems in Germany: ESI-D and Manchester Triage System (MTS)

Within Germany, the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) and the Manchester Triage System (MTS) are recognized as the two most frequently utilized primary assessment systems in emergency departments. While both systems aim to prioritize patients effectively, they operate on distinct philosophical underpinnings. The ESI, for instance, focuses on a combination of patient acuity and the anticipated number of resources required for care. In contrast, systems like the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) and the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), also five-level scales used internationally, tend to place a greater emphasis on presenting symptoms and diagnoses to determine safe waiting times.

The co-existence of ESI and MTS as dominant systems in Germany suggests a dynamic, though potentially complex, landscape for patient prioritization. Their differing philosophical approaches—resource-based for ESI versus symptom/diagnosis-based for MTS—imply that individual emergency departments may select one over the other based on their specific operational models, patient demographics, or institutional priorities. This situation also presents a challenge for achieving complete national standardization, as two distinct yet widely accepted "gold standards" are in play. A deeper examination of their comparative performance is therefore warranted to understand the implications for patient experience and outcomes across various German hospitals.

1.3. Legal and Regulatory Mandates for Triage in German Emergency Departments

A significant policy intervention in German emergency care occurred in 2018, when hospitals became legally obligated to implement a treatment prioritization system, commonly known as triage, in their emergency departments. This mandate was introduced with explicit objectives: to optimize workflows, alleviate the burden on medical staff, and ultimately ensure the provision of effective patient care. A crucial component of this legal requirement is the stipulation that hospitals participating in emergency care must provide an assessment of treatment priority for patients within ten minutes of their arrival in the ED.

Furthermore, the Joint Federal Committee (G-BA), a key decision-making body in the German healthcare system, has been tasked with establishing comprehensive guidelines for a qualified and standardized initial assessment of medical care needs. This initiative aims to make structured triage a nationwide mandatory practice, moving beyond mere recommendations to enforce a consistent standard in emergency care across the country. This top-down regulatory approach underscores a national commitment to enhancing patient safety and system efficiency by standardizing the critical first step in emergency patient management. While the mandate requires structured triage, it does not explicitly specify a single system, allowing hospitals the flexibility to choose between validated options such as ESI and MTS. This approach suggests an ongoing effort to refine and standardize emergency care, which may eventually lead to a more unified approach or clearer guidance on system selection.

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI): Foundational Principles

2.1. Historical Development and Core Philosophy of the US ESI System

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) was initially conceived and developed in 1998 by American emergency physicians Richard Wuerz and David Eitel. The foundational framework for ESI was built upon a conceptual model designed to assess a patient's physiological stability and their inherent risk for clinical deterioration. Following its initial development, the ESI was first implemented in two university teaching hospitals in 1999. Based on valuable feedback gathered from these pilot sites, the algorithm underwent further refinement and was subsequently expanded for implementation in five additional hospitals in 2000. This iterative development and refinement process, involving a multidisciplinary group of emergency professionals, underscores the system's evidence-based foundation and its adaptability in practical clinical settings. The ongoing maintenance of the ESI is currently overseen by the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA). The origin of the ESI in the United States, an environment characterized by high-volume emergency care, suggests that its design inherently prioritizes efficiency and rapid decision-making. These attributes make it particularly appealing and transferable to other healthcare systems facing similar demands, such as those in Germany.

2.2. The Five-Level Acuity Scale: Differentiating by Acuity and Resource Needs

The ESI is structured as a five-level emergency department triage algorithm, designed to stratify patients into distinct groups based on their clinical urgency. Patients are categorized from Level 1, representing the most urgent cases, to Level 5, indicating the least urgent. A defining characteristic of the ESI, which sets it apart from many other standardized triage algorithms, is its dual criteria for patient categorization: it considers both the acuity (severity) of the patient's medical condition and the number of resources their care is anticipated to require.

For the highest acuity levels, Levels 1 and 2, the primary determinant is urgency and patient acuity. Level 1 is reserved for patients requiring immediate life-saving intervention, while Level 2 is assigned to those at high risk of deterioration or presenting with a time-critical problem. In contrast, for Levels 3, 4, and 5, assuming the patient's vital signs are stable and there is no immediate life threat, the triage decision is predominantly driven by the estimated number of resources expected to be utilized for their care. This combination of acuity assessment with anticipated resource utilization provides a more nuanced prioritization compared to simpler triage models. This approach facilitates the efficient allocation of resources, directing high-acuity patients to immediate, critical care pathways, while channeling stable patients with predictable, lower resource needs to appropriate, often faster, treatment areas. Such a design directly addresses the challenge of managing patient flow effectively in busy emergency departments. The deliberate choice to combine these two factors aims to manage not only clinical risk but also operational efficiency, thereby allowing for the decentralization of medical care for low-complexity patients, which is vital in preventing overcrowding.

2.3. Defining "Resources" and Their Role in ESI Classification

The concept of "resources" is fundamental to the ESI algorithm, particularly for the classification of patients into lower acuity levels (Levels 3, 4, and 5). In the context of ESI, a "resource" is defined as any intervention or diagnostic tool that extends beyond a basic physical examination. Examples of services or procedures considered resources include radiologic imaging (such as X-rays, CT scans, or ultrasounds), laboratory tests, the application of sutures for wound repair, and the administration of intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) medications. Consultations with specialists are also counted as resources.

Conversely, certain interventions are explicitly not considered resources by the ESI algorithm. These include oral medications, simple wound care, the provision of crutches or splints, and the issuance of prescriptions. Basic assessments like anamnesis (patient history) and physical examinations are also not counted as resources. This precise definition is crucial for guiding triage nurses in making consistent decisions about the intensity of care a patient is likely to require.

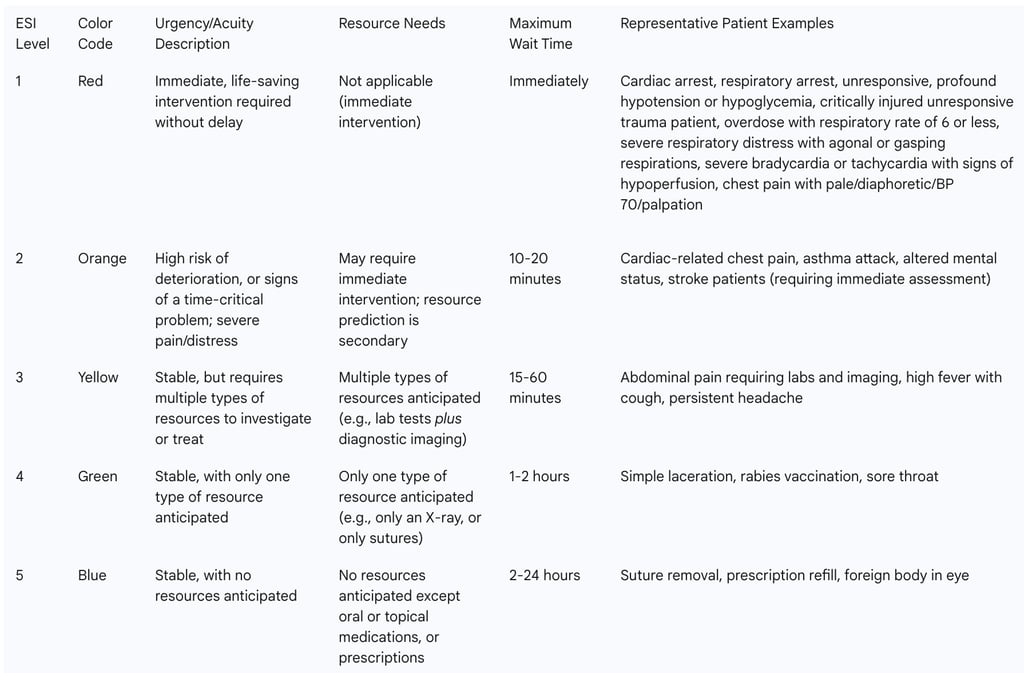

For stable patients, the number of anticipated resources directly determines their ESI level:

Level 3: Assigned to stable patients who are expected to require multiple types of resources to investigate or treat their condition. An example would be a patient with abdominal pain who needs both laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging.

Level 4: For stable patients where only one type of resource is anticipated. This could include a simple laceration requiring only sutures, or a patient needing only an X-ray for a suspected fracture, or a rabies vaccination.

Level 5: Reserved for stable patients who are expected to require no resources beyond oral or topical medications, or a prescription. Examples include suture removal, a prescription refill, or the removal of a foreign body from the eye.

The clarity provided by these definitions allows for standardized decision-making and the efficient allocation of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. By excluding basic interventions from the "resource" definition, the system prevents over-triage of minor complaints, ensuring that higher-level resources are reserved for patients with more complex needs. This mechanism directly contributes to managing emergency department flow and preventing unnecessary consumption of critical resources for low-acuity cases. Patients requiring fewer resources can be directed to "supertrack" or "fast areas," thereby reducing wait times for more complex cases and mitigating overcrowding.

2.4. General Applicability and Limitations of the ESI Algorithm

The Emergency Severity Index has demonstrated broad applicability and robustness, with numerous studies affirming its reliability, consistency, and accuracy across diverse populations, languages, age groups, and countries. Its widespread adoption is particularly notable in the United States, where approximately 94% of emergency departments utilized the ESI algorithm for triage as of 2019.

Despite its general effectiveness, the ESI algorithm does have identified limitations that necessitate careful consideration in its application:

Mass Casualty and Trauma Incidents: The ESI algorithm is not designed for and should not be used in certain mass casualty or major trauma-related incidents. In such scenarios, alternative rapid triage programs like START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment) or JumpSTART for pediatric patients are recommended.

Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): The ESI score has shown poor association with serious outcomes in patients suspected of having acute coronary syndrome. This suggests that for such critical conditions, the ESI should be supplemented with other validated clinical tools to improve the accuracy of triage.

Patient Stratification and Waiting Times: In some contexts, higher acuity patients may experience inappropriate stratification, potentially leading to longer waiting times. This indicates a need for vigilance and ongoing quality improvement efforts to ensure that the most urgent cases are consistently prioritized.

Subgroup Reliability: While generally reliable, the ESI's reliability may be moderate in specific subgroups, such as geriatric or pediatric patients. This highlights the complexities of assessing these vulnerable populations and the potential need for tailored approaches or additional assessment tools.

These limitations underscore that even a highly validated system like the ESI is not a universal solution and must be integrated into a broader, flexible emergency care framework. This framework should allow for specialized protocols and the exercise of clinical judgment in high-risk or complex scenarios. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for developing targeted training programs and implementing complementary assessment strategies to ensure optimal patient care across all presentations.

ESI-D: Adaptation, Validation, and Implementation in Germany

3.1. The Process of Cultural and Linguistic Adaptation for German-Speaking Regions

The successful transfer of a clinical tool like the Emergency Severity Index from its country of origin to a new healthcare system necessitates careful cultural and linguistic adaptation. For German-speaking countries, the ESI underwent a translation and cultural adaptation process. A significant finding from this endeavor was that only minor cultural adaptations were required during the translation process. This outcome strongly indicates the ESI's inherent universality and robustness, suggesting that its core principles of acuity and resource-based triage transcend specific cultural or healthcare system nuances, making it highly transferable.

A validated German translation of the ESI tool was published by a team from the emergency department of the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland. The minimal need for cultural adjustments is a powerful testament to the ESI's design, implying that if significant cultural hurdles existed, the adaptation process would have been considerably more complex, potentially affecting its reliability. This ease of translation supports its potential for broad acceptance and consistent application across diverse German emergency departments.

3.2. Empirical Validation of ESI-D: Reliability and Validity Studies

The successful implementation of any triage system hinges on its demonstrated reliability and validity. For the ESI-D, empirical studies in German-speaking regions have provided robust evidence supporting its effectiveness.

3.2.1. Inter-Rater Reliability: Consistency in Triage Decisions

Inter-rater reliability refers to the extent to which different healthcare professionals assign the same triage level to a given patient. For the German ESI, a study involving a sample of 125 patients reported a high inter-rater agreement, with a Cohen's weighted kappa (κ) of 0.985. This "almost perfect" agreement is a critical indicator of the system's consistency and reproducibility, meaning that trained healthcare professionals are highly likely to make similar triage decisions for the same patient. Such consistency is foundational for standardized care and equitable resource allocation within emergency departments.

A broader meta-analysis examining ESI reliability across studies both within and outside the United States further supported its substantial agreement and acceptable overall reliability, with kappa statistics ranging from 0.46 (moderate) to 0.98 (almost perfect). While the overall reliability is strong, it is also noted that reliability may be moderate in certain subgroups, such as geriatric or pediatric patients. These variations highlight areas where targeted training or further refinement of the algorithm's application might be beneficial to maintain optimal consistency. The strong kappa value for the German adaptation suggests that it successfully maintains the high level of consistency observed in the original ESI, which is paramount for the system's utility.

3.2.2. Predictive Validity: Correlation with Patient Outcomes and Resource Utilization

Predictive validity assesses how well a triage system's assigned levels correlate with actual patient outcomes and resource consumption. For the German ESI, several studies have provided compelling evidence:

Correlation with Resources: A study involving 2,114 patients in Germany found a Spearman's rank correlation coefficient of ρ = -0.567 between the ESI category and the number of resources utilized. This negative correlation indicates that lower ESI levels (signifying higher acuity) are indeed associated with a greater number of resources consumed, affirming the system's ability to predict resource intensity.

Correlation with Disposition and Hospitalization: The association (Kendall's τ) between ESI category and patient disposition was found to be τ = -0.429, and for hospitalization, it was τ = -0.453. These negative correlations demonstrate that lower ESI levels are reliably associated with higher rates of admission and specific patient dispositions, indicating the system's effectiveness in guiding patient placement.

Predictive Ability for Hospitalization/ICU Admission: The ESI-D demonstrated good to very good predictive power for critical outcomes. The areas under the curve (AUC) for the predictive ability of the ESI for general hospitalization were 0.788, and for hospitalization to an ICU, they were 0.856. These AUC values are strong indicators of the ESI's diagnostic accuracy in identifying patients who genuinely require higher levels of care.

Mortality Prediction: The ESI triage level has been significantly associated with hospitalization rate, length of stay in the emergency department, resource utilization, and 1-year mortality. Patients assigned to ESI Level 1 faced the highest risk of death in the ED (4%), while patients triaged to ESI Level 5 exhibited very low or zero mortality rates. This establishes a clear link between accurate triage and improved patient outcomes.

However, it is important to acknowledge some nuanced findings. One study presented a contrasting view, suggesting that ESI failed to predict both resource consumption and ED length of stay (LOS) in its specific patient population, particularly performing poorly in older and oldest adult groups. This suggests that while ESI is robust for identifying immediate acuity and the need for inpatient care, its predictive power for longer-term resource needs or overall ED efficiency might be more complex and influenced by other factors beyond initial triage, especially for vulnerable populations. This calls for a balanced interpretation of ESI's capabilities and highlights a potential area for further investigation or the use of supplementary tools.

3.3. Special Considerations for Pediatric Patients within ESI-D

Pediatric patients represent a unique and vulnerable population within the emergency department, requiring distinct considerations during triage. Their physiological and psychological responses to stressors differ significantly from adults, and their limited ability to communicate effectively can make rapid and accurate assessment more challenging. Recognizing these differences, the ESI framework emphasizes that for pediatric patients, the ESI algorithm should be used in conjunction with the Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) and a focused pediatric history to accurately assign an acuity level. The ESI handbook itself includes a dedicated section on applying the ESI algorithm to pediatric populations, acknowledging these specific needs.

Despite these guidelines, studies have indicated that the reliability of ESI may be moderate in pediatric patients. Furthermore, some research conducted in specific hospital settings has shown low validity and reliability for ESI in pediatric triage. These findings highlight the inherent complexity of pediatric triage and underscore the ongoing need for specialized training, continuous quality improvement initiatives, and potentially further adaptation or supplementary tools tailored specifically for this vulnerable group. The explicit recognition of children as a "special population" within the ESI framework demonstrates a commitment to tailored care, yet the observed variations in performance suggest that the practical execution of ESI for children may require even more specialized expertise and ongoing refinement.

3.4. Key Institutions and Professional Associations Involved in ESI-D Adoption and Research

The widespread adoption and credibility of the Emergency Severity Index are significantly bolstered by the endorsement of major professional bodies. In the United States, for instance, both the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) actively support the adoption of valid five-level triage scales, including the ESI. This support from leading professional organizations provides a strong foundation for the ESI's clinical acceptance and implementation.

In Germany, while there is no single explicit endorsement of ESI-D over the Manchester Triage System (MTS) in the provided information, the Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin e.V. (DIVI) plays a crucial role in shaping emergency and intensive care. DIVI is dedicated to promoting scientific progress and improving structures in these medical fields, including the development of national guidelines. DIVI's involvement in establishing national consensus on triage procedures suggests its significant influence on the adoption and standardization of ESI-D within the German healthcare system. This implies that the integration of ESI-D is part of a broader, consensus-driven effort to standardize emergency care practices, rather than a top-down imposition of a singular system.

It is important to clarify that the acronym "ESI" is used by several distinct organizations and initiatives that are unrelated to the Emergency Severity Index triage system. For example:

The European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) is a non-profit association focused on improving knowledge and care in the field of Primary Immunodeficiency (PID), including maintaining a patient registry and promoting genetic testing for these conditions. This is a medical society, but not related to emergency triage.

The Elisabeth-Selbert-Initiative (ESI) is a program in Germany that provides protection and support for threatened human rights defenders. This is a human rights initiative.

The European Scientific Institute (ESI) is an academic platform that publishes peer-reviewed journals and organizes scientific conferences. This is an academic publishing and event organization.

The ESI-CorA project refers to an Emergency Support Instrument from the European Commission for monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater.

The Everyday Stressors Index (ESI) is a psychological questionnaire for assessing daily stress.

These distinct entities, despite sharing the "ESI" acronym, are not related to the Emergency Severity Index triage system discussed in this report. Maintaining this distinction is crucial for accurate understanding and avoiding confusion.

4. Operationalizing ESI-D: A Detailed Algorithmic Approach

4.1. Step-by-Step ESI-D Triage Algorithm: From Initial Assessment to Level Assignment

The application of the ESI-D triage algorithm begins immediately upon a patient's arrival at the emergency department. The process is designed to be rapid and efficient, typically involving a brief, focused assessment conducted by a triage nurse. While the specific visual representation may vary, the ESI algorithm conceptually follows a flowchart or decision tree structure to guide the triage professional through a series of critical questions. This structured approach ensures consistency and reduces variability in triage decisions, which is particularly important in high-stress emergency environments.

The core of the ESI-D algorithm involves a sequence of key decision points:

Immediate Life-Saving Intervention Required? The first and most critical step is to determine if the patient's condition necessitates immediate life-saving intervention without any delay. If the answer is affirmative, the patient is assigned ESI Level 1. This step rapidly identifies the most critical patients who cannot wait for care.

High Risk, Severe Pain, or Time-Critical Problem? If a life-saving intervention is not immediately required, the next consideration is whether the patient presents with a high risk of clinical deterioration, severe pain or distress, or a time-critical problem. If any of these conditions are met, the patient is assigned ESI Level 2. This step incorporates an assessment of vital signs and the potential for rapid decline.

Anticipated Resource Needs? For patients who are deemed stable and do not fit into Level 1 or 2 criteria, the subsequent steps focus on predicting the number of resources that will be required for their care. This estimation of resource utilization is the primary determinant for assigning ESI Levels 3, 4, and 5.

Vital Signs Assessment (Up-Triage): Throughout the assessment, vital signs play a crucial role. Patients initially assessed as Level 3 may be "up-triaged" to Level 2 if they exhibit "danger zone" vital signs, such as an abnormal respiratory rate, heart rate, or oxygen saturation. This mechanism ensures that patients whose acuity is rapidly escalating are identified and re-prioritized promptly.

The step-by-step nature of the ESI algorithm, moving from immediate life-threat to resource prediction, provides a structured and logical framework for rapid decision-making under pressure. The emphasis on gathering "sufficient" information rather than exhaustive data collection at triage is key to maintaining its speed and efficiency.

4.2. Criteria for Each ESI-D Level (1-5) with Illustrative Examples

The ESI-D employs a five-level categorization system, each associated with specific criteria, anticipated resource needs, and recommended maximum waiting times. This structured approach ensures consistent prioritization and patient flow.

The detailed examples provided for each ESI level are crucial for standardized application and training. They offer concrete scenarios that assist triage nurses in translating abstract criteria into practical, real-time decisions. The explicit maximum wait times associated with each level further underscore the system's role in managing patient expectations and ensuring that care is delivered in a timeframe commensurate with the assessed urgency of their condition.

4.3. The Role of Triage Nurses and Other Healthcare Professionals in ESI-D Application

The effective application of ESI-D relies heavily on the expertise and judgment of trained healthcare professionals, primarily paramedics and registered nurses who work in hospital settings. The triage nurse is responsible for conducting a brief, focused assessment upon the patient's arrival to assign an appropriate acuity level. A critical aspect of this role, particularly for ESI Levels 3, 4, and 5, involves estimating the number of resources that will be required for the patient's care. This estimation draws significantly on the nurse's previous experience with patients presenting similar injuries or complaints.

The successful implementation of the ESI algorithm is not merely a matter of following a flowchart; it demands a high degree of clinical acumen. Consequently, guidelines stipulate that the ESI algorithm should be used strictly by individuals with at least one year of emergency department experience who have successfully completed a comprehensive triage program. In many European countries, including Germany and Switzerland, triage is specifically performed by specially trained nursing staff, highlighting the recognition of their critical role in this initial assessment process. This emphasis on experienced and specially trained nursing staff underscores that while the ESI algorithm provides a structured framework, its effective application relies heavily on the clinical judgment and expertise of the triaging professional. This human element, particularly the nuanced estimation of resource needs based on accumulated experience, is a critical success factor and a potential source of variability if training is insufficient. It reinforces the understanding that ESI is a powerful tool designed to aid, rather than replace, the skilled healthcare professional.

4.4. Essential Training and Educational Programs for ESI-D Competency in Germany

Successful and consistent implementation of the ESI-D system is fundamentally dependent on comprehensive and ongoing educational programs for all healthcare professionals involved in triage. Such programs are crucial for ensuring the rapid identification of patients requiring immediate attention and the efficient routing of others to appropriate care pathways. Training triage nurses in standardized ESI methodology is highly recommended, encompassing vital sign assessment and the recognition of high-risk presentations.

The Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) offers a comprehensive suite of triage education resources, including a dedicated handbook and online courses, which provide foundational knowledge and supporting research for applying the ESI algorithm. In Germany, specific courses are available to develop ESI-D competency. For example, programs titled "Effektive Patienten-Ersteinschätzung in der Notaufnahme: Das ESI-Triage-System" (Effective Patient Initial Assessment in the ED: The ESI Triage System) are offered for a target audience that includes nurses, paramedics, medical assistants, and physicians working in emergency departments, as well as other interested individuals.

These educational programs typically cover a wide range of content essential for effective triage, including:

The history and evolution of triage concepts.

An overview of various triage systems in use.

The legal and regulatory foundations governing triage in Germany.

An in-depth exploration of the ESI triage algorithm, with practical application through diverse case studies from various medical specialties.

Techniques for assessing symptoms, accurate documentation, and effective communication during the triage process.

The benefits of such rigorous training are multifaceted, contributing to improved patient safety, more efficient resource allocation, enhanced assessment accuracy, better management of patient flow, and increased confidence among triage personnel. The extensive availability and emphasis on comprehensive training programs for ESI-D underscore that successful implementation is highly dependent on human capital development. This is not merely about understanding an algorithm but about developing the nuanced clinical judgment and consistent application required for effective triage. The structured nature of these courses, incorporating case examples and practical simulations, directly addresses the need for competency and helps to reduce variability in triage decisions across different practitioners. The recurring emphasis on a "comprehensive ESI educational program" throughout the literature highlights that the algorithm's effectiveness is intrinsically linked to the expertise of its users, making investment in training as important as the tool itself.

Impact of ESI-D on Emergency Department Performance and Patient Care

5.1. Optimizing Patient Flow and Reducing Length of Stay

The implementation of effective triage systems like ESI-D is crucial for managing patient flow within emergency departments, particularly when the demand for medical action surpasses available capacity. Such imbalances pose a significant threat to patient safety and the overall quality of care. ESI implementation has been empirically shown to contribute to a notable decrease in patient length of stay (LOS) in the emergency department. For instance, one study observed a reduction in average patient LOS from 157.02 minutes to 86.96 minutes following ESI adoption. This quantifiable reduction in LOS represents a direct and significant benefit, indicating improved operational efficiency within the ED.

The ESI system's design, which combines acuity assessment with anticipated resource utilization, facilitates a more nuanced prioritization of patients. This capability enables well-implemented ESI programs to rapidly identify patients requiring immediate attention while simultaneously identifying those who can be safely and efficiently directed to a "fast-track" or urgent-care area. The ability to channel lower-acuity cases to these expedited pathways is a key mechanism by which ESI optimizes patient flow, preventing them from unduly burdening higher-acuity treatment areas. This strategic routing directly contributes to managing overcrowding and enhancing overall patient satisfaction by reducing wait times for all patient categories.

5.2. Strategic Resource Allocation and Management of ED Overcrowding

A primary objective of the ESI system is to enable emergency departments to strategically allocate their limited resources to the most critically ill patients. By categorizing patients based on their anticipated resource needs, ESI assists in managing situations where resources are constrained. The system is considered a valuable tool for assigning acceptable maximum waiting times, thereby protecting critical patients from being overlooked, especially in overcrowded emergency departments.

Despite the benefits of triage systems, overcrowding remains a significant and persistent challenge in many German emergency departments, leading to delays in care for time-critical and severely ill patients. While ESI-D significantly improves resource

allocation by directing high-acuity patients to immediate attention and necessary interventions, the continued prevalence of overcrowding suggests that triage is one component within a larger, complex system. Addressing overcrowding fully requires comprehensive systemic solutions that extend beyond the triage desk, encompassing factors such as adequate staffing levels, efficient inpatient bed availability, and streamlined discharge processes. Thus, while ESI optimizes internal ED resource use, external hospital-wide factors heavily influence the overall management of crowding.

5.3. Enhancing Patient Safety and Clinical Outcomes through ESI-D Prioritization

The effectiveness of the ESI system in improving patient outcomes is rooted in its ability to provide nuanced patient prioritization. By rapidly identifying patients in need of immediate attention, ESI serves as a critical safeguard against adverse events. The system has demonstrated high sensitivity in diagnosing critical conditions such as sepsis and septic shock, with ESI Level 1 showing an 88.5% sensitivity for septic shock, enabling prompt intervention.

Furthermore, ESI classification reliably correlates with the need for higher levels of care. Patients assigned to ESI Levels 1 and 2 frequently require admission to Intensive Care Units (ICU) or Intermediate Care (IMC) units. Specifically, ESI Level 1 patients exhibit the highest admission rates to ICU (27%) and IMC (37%). The system also effectively stratifies mortality risk: patients triaged to ESI Level 1 face the highest risk of death in the ED (4%), whereas very low or zero mortality rates are observed for patients in lower acuity levels. This strong predictive power for severe outcomes directly translates into enhanced patient safety. By ensuring that the most critically ill patients are promptly identified and prioritized, ESI reduces the risk of adverse events and significantly improves the likelihood of positive clinical outcomes. This underscores its profound value not only as an efficiency tool but, more importantly, as a fundamental intervention for patient safety.

5.4. Identified Strengths and Limitations in ESI-D's Practical Application

The practical application of ESI-D in emergency departments reveals a combination of significant strengths and areas requiring ongoing attention.

Strengths of ESI-D:

Reliability and Accuracy: ESI has consistently been found to be reliable, consistent, and accurate across multiple studies, languages, and settings.

Speed of Triage: The algorithm facilitates rapid patient assessment, with an average triage time of approximately 2 minutes and 27 seconds.

Sepsis Identification: It demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing critical conditions such as sepsis and septic shock.

Correlation with Outcomes: ESI shows a good correlation with crucial outcomes, including hospital admission rates and resource utilization, indicating its effectiveness in guiding patient management.

Identification of Severely Ill Patients: The system is effective in identifying severely ill patients across all age groups by accurately predicting mortality and hospital admissions.

Limitations of ESI-D:

Tendency Towards Level 2: There is an observed tendency for the ESI to allocate patients to Level 2. While this might reflect a cautious approach to minimize undertriage for high-risk cases, it could also contribute to overtriage if not carefully managed.

Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): The ESI score is poorly associated with serious outcomes in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome, suggesting that supplementary clinical tools are necessary for accurate assessment in these specific cases.

Inappropriate Stratification for High-Acuity Patients: In some contexts, patients with genuinely high acuity may face inappropriate stratification, potentially leading to longer waiting times.

Pediatric Triage Challenges: Some studies have indicated low validity and reliability for ESI in pediatric triage within specific settings , and its reliability may be moderate in pediatric patients generally.

Prediction for Older Adults: One study found that ESI did not consistently predict ED length of stay or resource consumption across all age groups, particularly performing poorly in older and oldest adult populations. This suggests that while ESI is effective at initial prioritization, other factors might influence later resource use or total ED time for complex patient groups.

These identified strengths and limitations provide a nuanced understanding of ESI-D's practical utility. While it excels in speed, consistency, and the rapid identification of acutely ill patients for immediate intervention, its caveats for specific conditions and patient populations highlight areas where supplementary tools, enhanced clinical judgment, and ongoing refinement are essential for maximizing its overall effectiveness and mitigating its shortcomings.

Comparative Analysis: ESI-D versus Manchester Triage System (MTS) in Germany

6.1. Fundamental Differences in Algorithmic Design and Triage Philosophy

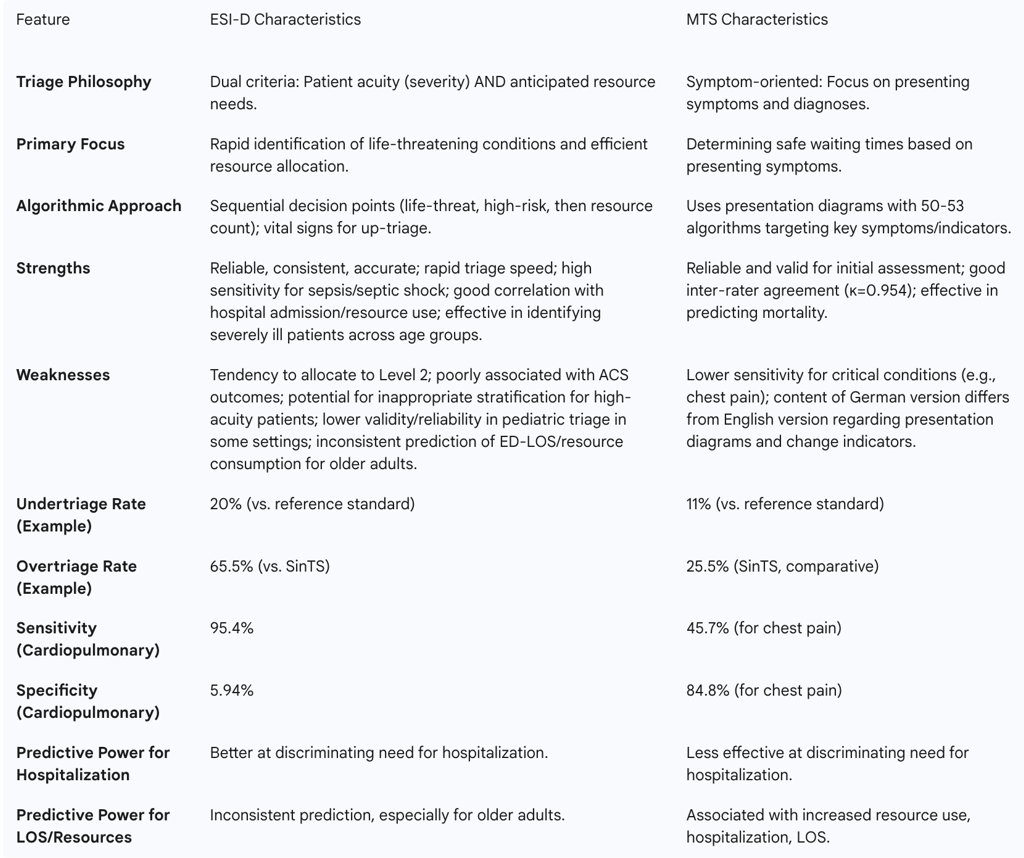

The selection of a triage system in German emergency departments often comes down to a choice between the Emergency Severity Index (ESI-D) and the Manchester Triage System (MTS). These two systems, while both five-level acuity scales, are built upon fundamentally different algorithmic designs and triage philosophies.

ESI-D's approach is rooted in a dual assessment: it considers both the patient's immediate acuity (severity of their medical condition) and the anticipated number of resources their care will require. For the most critical patients (Levels 1 and 2), the decision is primarily driven by urgency and acuity, such as the need for immediate life-saving intervention or the presence of a high-risk, time-critical problem. For stable patients (Levels 3, 4, and 5), the classification hinges on the predicted resource consumption. This emphasis on resources allows for rapid "fast-tracking" of stable patients who require minimal interventions, thereby optimizing patient flow.

In contrast, the Manchester Triage System (MTS) focuses more heavily on presenting symptoms and diagnoses to determine how long a patient can safely wait for care. It utilizes a structured approach with presentation diagrams backed by 50 algorithms. These algorithms guide the triage nurse through specific patient complaints, targeting key symptoms or "indicators" to allocate patients to one of the five priority levels.

This core philosophical difference leads to distinct triage pathways and patterns of resource utilization. ESI-D's resource-driven emphasis allows for the rapid identification of patients suitable for streamlined care, while MTS's symptom-driven approach might lead to different wait times for similar conditions depending on the specific flowchart followed. The choice between these systems is therefore not solely about their statistical reliability but also about the desired operational flow within the emergency department and the institution's risk tolerance.

6.2. Comparative Performance: Undertriage, Overtriage, Sensitivity, and Specificity

Comparative studies between ESI-D and MTS in Germany reveal a complex performance profile, with each system demonstrating particular strengths and weaknesses in different metrics.

Undertriage: One study indicated that ESI had a significantly higher percentage of undertriage (20%) compared to MTS (11%) when assessed against a reference standard. When combining urgency levels 4 and 5, the undertriage rate was 14% for ESI versus 11% for MTS. This suggests that ESI might, in some instances, underestimate the urgency of certain conditions, potentially leading to delays in care for a subset of patients.

Overtriage: In a comparison with the SINEH triage scale (SinTS), ESI demonstrated a total mistriage rate of 66.8%, comprising 1.3% undertriage and a substantial 65.5% overtriage. In contrast, SinTS showed a total mistriage of 29.63% (4.13% undertriage, 25.5% overtriage). The overtriage rate for ESI was significantly higher (p=0.001) than for SinTS. This high overtriage rate for ESI could lead to increased resource strain, as more patients are treated as sicker than their actual condition might warrant.

Sensitivity and Specificity: For patients presenting with cardiopulmonary complaints, ESI demonstrated a high sensitivity of 95.4% but a low specificity of 5.94%, resulting in an accuracy of 32.79%. Conversely, MTS, when applied to chest pain patients, showed a sensitivity of 45.7% and a specificity of 84.8%, with an accuracy of 81.9%. Another study noted that both ESI and MTS exhibited low sensitivity across all urgency levels but maintained high specificity (greater than 92%) for Levels 1 and 2. The high sensitivity of ESI for critical conditions, such as chest pain leading to immediate ECG monitoring, indicates a strong preference for patient safety, even if it results in higher overtriage compared to systems like MTS, which might triage such patients to a waiting area.

The differences in sensitivity and specificity highlight that these systems excel in different aspects. The choice between them often depends on an institution's priorities—for example, minimizing missed critical cases (favoring ESI's high sensitivity for severe conditions) versus optimizing flow and resource utilization for all patients.

6.3. Differential Predictive Power for Hospitalization, Resource Use, and Mortality

The predictive power of ESI-D and MTS for patient outcomes such as hospitalization, resource utilization, and mortality also presents a varied picture in comparative analyses.

One study indicated that ESI urgency levels are better at discriminating the need for hospitalization compared to MTS and a third system, NTS. The adjusted risk of hospital admission was observed to increase significantly more with rising urgency levels in ESI. This suggests that ESI may be more effective in identifying patients who genuinely require inpatient care. Additionally, the same study found that resource utilization was substantially lower in the lowest urgency level of ESI compared to MTS and NTS. While mortality rates were generally low for both populations, ESI was identified as a better predictor of admission than MTS.

However, other research introduces a significant nuance. A Finnish study, for instance, found that ESI failed to predict both resource consumption and ED length of stay (LOS) in its specific patient population, particularly performing poorly in older and oldest adult groups. This contradictory finding implies that while ESI may be effective at identifying the immediate need for inpatient care, its ability to precisely forecast resource usage or the total duration of an ED stay might be limited, especially for complex cases. Such discrepancies suggest that factors beyond initial triage can influence these outcomes, and that a system's "validity" can be measured against different outcomes, with strengths in one area not necessarily translating to another.

6.4. Current Prevalence and Endorsement of ESI-D and MTS in German EDs

Both the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) and the Manchester Triage System (MTS) are widely utilized in emergency departments across German-speaking Europe. This widespread adoption indicates that both systems are considered viable and effective for initial patient assessment in the region.

Regarding validation, some studies explicitly state that of the two, only ESI has been formally validated in German-speaking countries. However, other sources indicate that the German version of the MTS has also undergone validation processes and is considered a reliable and valid instrument for initial assessment. This discrepancy in reported validation status might reflect ongoing research or different criteria applied in various studies.

Furthermore, systematic reviews comparing the two systems have often concluded that there is no clear preference for either ESI or MTS, as their overall performance appears comparable across various metrics. The continued co-prevalence of both systems, despite some studies suggesting ESI's superior predictive power for hospitalization, indicates that practical adoption is influenced by a multitude of factors beyond just empirical superiority in all metrics. These factors likely include historical implementation within specific institutions, the perceived ease of training for staff, the clinical utility as experienced by practitioners, and the specific needs or patient demographics of a particular department. The lack of a definitive "clear preference" from systematic reviews suggests that both systems offer comparable overall performance, allowing institutions a degree of flexibility in their choice of triage methodology. This implies that a "one-size-fits-all" approach to triage system adoption might not be practical or even desirable across the diverse landscape of German emergency care.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of ESI-D and Manchester Triage System (MTS)

Challenges, Future Directions, and Recommendations

7.1. Persistent Challenges in Triage Implementation and Accuracy in Germany

Despite the widespread adoption and proven efficacy of structured triage systems like ESI-D, several persistent challenges continue to impact their optimal implementation and accuracy in German emergency departments. A fundamental understanding emerging from current research is that formalized triage systems, while crucial, are often insufficient on their own to comprehensively categorize the urgency of emergency and acute patients. This indicates that effective patient management requires a synergistic combination of different measures, critically involving an interprofessional team approach.

Emergency department overcrowding remains a significant and pervasive issue, posing a major threat to patient safety and the quality of care, even with triage systems in place. This suggests that triage, while a necessary component, is not a standalone solution for systemic issues within the broader healthcare ecosystem. Another inherent challenge lies in the absence of a universally accepted "gold standard" for actual urgency, which complicates the definitive assessment and comparative evaluation of triage systems' accuracy. This lack of a perfect benchmark makes it difficult to definitively declare one system superior to another across all contexts. Furthermore, specific challenges persist in the triage of pediatric and geriatric patients, where studies have indicated that reliability may be moderate or validity potentially low in some settings. These populations present unique physiological and communication complexities that can challenge even the most robust triage algorithms. These challenges collectively highlight that while triage is a vital tool, it must be integrated within a broader interprofessional and systemic approach, addressing issues such as staffing, inpatient bed flow, and specialized care pathways to truly optimize ED performance.

7.2. Emerging Research Areas and Potential for Further ESI-D Refinement

The field of emergency triage is dynamic, with ongoing research aiming to enhance the precision and effectiveness of systems like ESI-D. One key area of focus is the need for further research to improve the accuracy of triage scales, particularly for patients presenting with cardiopulmonary complaints, where current systems may show limitations in specificity. This targeted research aims to refine algorithms for better diagnostic evaluation in these time-critical conditions.

Another promising area involves the development and integration of predictive risk scores. For instance, the TRIAL risk score, based on routinely collected baseline and laboratory data, has shown potential in predicting mortality and informing disposition decisions. Such scores could augment ESI-D by providing an additional layer of objective data to support triage decisions, especially for complex cases. The increasing interest in artificial intelligence (AI) applications in healthcare, as seen in research related to Inborn Errors of Immunity (IEI) , also suggests a future where AI could play a role in enhancing triage systems. AI could potentially analyze vast datasets to identify subtle patterns, predict outcomes with greater accuracy, and offer decision support, thereby improving both accuracy and efficiency beyond current capabilities. Ultimately, a continuous focus on optimizing patient flow through the emergency department remains a paramount objective, with ongoing research contributing to strategies designed to prevent overcrowding and improve overall operational efficiency. These advancements could lead to further refinements of ESI-D, making it even more precise and adaptive to evolving patient needs and healthcare complexities.

7.3. Recommendations for Policy Makers, Healthcare Providers, and Educators

To maximize the benefits of the German Emergency Severity Index (ESI-D) and address the persistent challenges in emergency care, targeted recommendations are crucial for various stakeholders.

For Policy Makers:

Sustained Support for Structured Triage: Policy makers should continue to support the mandatory implementation of structured triage systems across all German emergency departments. This includes ensuring consistent application of guidelines developed by authoritative bodies such as the Joint Federal Committee (G-BA) and the Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin (DIVI).

Investment in Research and Data Collection: Allocate resources for national data collection and research initiatives aimed at further refining triage systems. This research should specifically address identified limitations in particular patient populations (e.g., pediatrics, geriatrics) or conditions (e.g., acute coronary syndrome) to enhance accuracy and effectiveness.

Integration with Systemic Flow Management: Consider developing national standards or best practice guidelines that integrate triage systems with broader patient flow management strategies. This holistic approach is essential for effectively combating emergency department overcrowding, which extends beyond the triage desk to encompass inpatient bed availability and discharge processes.

For Healthcare Providers (Hospitals & EDs):

Comprehensive and Ongoing Training: Prioritize comprehensive and continuous ESI-D training for all staff involved in triage. Training should emphasize the development of clinical judgment, accurate vital sign interpretation, and special considerations for pediatric and geriatric patients, given the noted complexities in these groups.

Robust Quality Assurance Programs: Implement rigorous quality assurance programs for ESI-D. This includes regular inter-rater reliability checks to ensure consistency among triage professionals and routine audits of triage decisions against actual patient outcomes to identify areas for improvement.

Strategic Use of Supplementary Tools: Explore and integrate supplementary clinical tools for specific high-risk conditions, such as acute coronary syndrome, where ESI alone may have recognized limitations. This ensures that all critical conditions are accurately identified and managed.

Holistic Patient Flow Management: Integrate ESI-D within a broader, holistic patient flow management strategy. This means addressing bottlenecks that occur beyond the triage point, such such as delays in inpatient bed availability, inefficiencies in diagnostic services, and slow discharge processes, to optimize overall ED throughput.

For Educators:

Advanced Training Modules: Develop advanced ESI-D training modules that focus on complex case scenarios, high-risk presentations, and the nuances of triage for pediatric and geriatric patients. This will equip professionals with the specialized skills needed for challenging situations.

Interprofessional Training: Incorporate interprofessional training programs that emphasize collaboration and communication among nurses, paramedics, and physicians during the triage process. This fosters a cohesive team approach to patient assessment and management.

Promote Research: Actively promote and support research into the efficacy of ESI-D across diverse German healthcare settings and patient populations. This continuous inquiry is vital for adapting the system to evolving needs and ensuring its long-term relevance and effectiveness.

These recommendations synthesize the identified challenges and opportunities, providing actionable steps for various stakeholders. The emphasis on continuous training, rigorous quality assurance, and systemic integration reflects a mature understanding that triage implementation is not merely about adopting a tool, but about cultivating a comprehensive and adaptive emergency care environment. The call for further research underscores the dynamic nature of emergency medicine and the need for ongoing adaptation to leverage the full potential of ESI-D.

7.4. The Role of Interprofessional Collaboration in Advancing Emergency Triage

A recurring theme throughout the analysis of emergency triage, particularly in the German context, is the critical importance of interprofessional collaboration. The evidence strongly suggests that structured primary assessment using formalized systems alone is often insufficient; instead, effective triage necessitates a combination of different measures delivered by a cohesive interprofessional team. This perspective acknowledges that triage is not an isolated nursing function but a complex, shared responsibility that benefits from the diverse expertise of various healthcare disciplines.

The Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin (DIVI), for instance, actively promotes interdisciplinary and multiprofessional collaboration in intensive and emergency medicine. This organizational emphasis aligns with the understanding that a holistic approach, involving seamless communication and shared decision-making among physicians, nurses, paramedics, and other specialists, leads to a more comprehensive patient assessment and a smoother patient journey through the emergency department. The future of optimal triage lies in fostering such collaborative environments, breaking down traditional professional silos, and ensuring that all members of the emergency care team contribute their unique perspectives to patient prioritization and management. This integrated approach enhances the overall effectiveness of systems like ESI-D, ensuring that patient care is not only timely but also comprehensive and coordinated from the moment of arrival.

Conclusion

The German Emergency Severity Index (ESI-D), a meticulously adapted and validated five-level triage system, has firmly established itself as a pivotal tool in German emergency departments. Its core strength lies in its unique dual approach, which combines an assessment of patient acuity with a prediction of anticipated resource needs. This methodology effectively prioritizes patients, optimizes patient flow, and significantly enhances patient safety by ensuring that the most critically ill individuals receive immediate attention and appropriate care.

Despite its demonstrated successes, the implementation of ESI-D continues to navigate persistent challenges, notably the pervasive issue of emergency department overcrowding and the complexities inherent in triaging specific patient populations, such as pediatrics and geriatrics. The ongoing co-existence and comparative performance with the Manchester Triage System (MTS) further highlight the nuanced considerations influencing triage system selection and application in Germany.

To fully leverage ESI-D's potential in the evolving landscape of German emergency medicine, sustained investment is imperative across several key areas. This includes comprehensive and continuous training programs for all triage personnel, ensuring the development of sophisticated clinical judgment. Rigorous quality assurance initiatives are essential to monitor consistency and accuracy of triage decisions. Furthermore, fostering robust interprofessional collaboration among all emergency care disciplines will ensure a holistic and coordinated approach to patient management. Continuous research and adaptation are vital to address identified limitations, integrate emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, and refine the system to meet the dynamic demands of modern emergency healthcare.