The Brazilian Triage Landscape

Brazil's public healthcare system, the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), the process of triage in emergency departments is not merely a clinical sorting mechanism. It represents a profound expression of national health policy, rooted in a philosophical commitment to humanized, equitable care.

In the intricate and sprawling landscape of Brazil's public healthcare system, the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), the process of triage in emergency departments is not merely a clinical sorting mechanism. It represents a profound expression of national health policy, rooted in a philosophical commitment to humanized, equitable care. Understanding the function of triage protocols in Brazil requires an initial examination of this foundational architecture, which elevates the act of prioritization from a procedural necessity to a political and ethical imperative.

The HumanizaSUS Policy: Beyond Clinical Sorting to Humanized Care

The guiding framework for triage in Brazil is the Política Nacional de Humanização (PNH), widely known as HumanizaSUS. Launched in the early 2000s, this policy was conceived to address systemic issues of fragmented care, impersonal treatment, and power imbalances within the SUS. The PNH is not a standalone program but a transversal policy intended to permeate all aspects of healthcare delivery and management, from the front desk to the intensive care unit. Its core values are the autonomy and protagonism of individuals, co-responsibility among patients and providers, the establishment of solidarity-based bonds, and collective participation in the management process.

Official documents describe the PNH as a "paradigma ético-estético" (ethical-aesthetic paradigm), signaling a deliberate effort to transform the very culture of care within the SUS. This framing is crucial because it moves the discussion beyond operational efficiency to the quality and nature of human interaction in healthcare settings. The decision to embed triage within this policy was a conscious one. By linking the initial point of patient contact—often the most fraught and anxious moment—to the principles of humanization, the Ministry of Health sought to use triage as a vehicle for systemic change. This approach resists the commodification of healthcare relationships and instead affirms the state's responsibility to provide care that is not only clinically effective but also dignifying and respectful. In this context, triage becomes a political act, a micro-political strategy to enact the core constitutional principles of the SUS—universality, integrality, and equity—at the most contentious and crowded gateway to the system: the emergency department door.

Acolhimento com Classificação de Risco (ACCR): The National Mandate for Risk-Based Prioritization

The primary instrument through which the PNH is operationalized in emergency settings is the Acolhimento com Classificação de Risco (ACCR), which translates to "Welcoming with Risk Classification" or "Embracement with Risk Classification". The ACCR framework was developed to replace the traditional and often chaotic "first-come, first-served" model, described as a "circulação desordenada" (disordered circulation) of users, with a structured, dynamic process of prioritization. Its fundamental purpose is to identify and prioritize patients who require immediate treatment based on their potential risk, the potential for their condition to worsen, or their degree of suffering.

The missions of ACCR are explicitly threefold: to be an instrument that welcomes the citizen and guarantees access, to humanize the care provided, and to ensure that attention is both rapid and effective. It is critical to note that ACCR is not a tool for diagnosis. Rather, it is a system of prioritization that relies on "escuta qualificada" (qualified listening) and a protocol-based assessment of signs and symptoms to determine the order of care.

The choice of the term Acolhimento ("welcoming" or "embracement") is deeply significant and represents a key Brazilian innovation in the field of triage. It intentionally signals a broader function than the English term "triage." Ministry of Health documents define acolher as an act of approximation, of "being with" and "close to" the patient, implying an attitude of inclusion and the formation of an initial therapeutic relationship. This mandate requires the triage professional, typically a nurse, not only to classify clinical risk but also to actively listen to the patient's concerns, provide clear information about their classification and expected waiting times, and manage the anxiety inherent in an emergency situation. This "welcoming" component is designed to humanize the encounter from the very first moment and mitigate the negative psychological impacts of waiting, a crucial distinction from many international triage systems that are more narrowly focused on rapid sorting.

From Ordinance to Practice: The Historical Evolution of Triage within the SUS

The formal institutionalization of triage within the SUS has been a gradual and evolving process. The foundational step was the Ministry of Health's Ordinance No. 2048 in 2002, which first officially recommended the implementation of patient triage in all emergency departments across the country. This recommendation laid the groundwork for a more structured policy.

Following this ordinance, the concept was integrated into the broader philosophical framework of the PNH, with the first HumanizaSUS documents on ACCR being published in 2004. These early documents established the ethical and operational principles of the new model. The policy was further detailed and consolidated in a key 2009 publication, "Acolhimento e Classificação de Risco nos Serviços de Urgência," which provided more specific guidelines for implementation.

A pivotal moment in the evolution of ACCR came in 2011 with the establishment of the Rede de Atenção às Urgências (Urgency Care Network) through Portaria No. 1.600. This major structural reform of the SUS made ACCR a mandatory, foundational component of all designated points of urgent and emergency care, cementing its role as a central organizing principle for patient flow nationwide.

Since then, the ACCR framework has demonstrated its adaptability by expanding beyond general emergency care into specialized fields. The Ministry of Health has released specific manuals for applying ACCR principles in obstetrics (2015) and for psychosocial care centers (CAPS) (2017). This trajectory reveals a clear maturation of the concept. It evolved from a general recommendation for EDs into a sophisticated and mandatory governance model for managing access and prioritizing care across diverse and complex pathways within the entire SUS. This demonstrates its perceived success and value as a flexible and effective policy tool by national health authorities.

The Manchester Triage System: De Facto Standard in Brazil

While the ACCR provides the philosophical and policy framework, the clinical tool most widely used to execute risk classification in Brazil is the Manchester Triage System (MTS). Its adoption represents a strategic decision to align with a globally recognized standard while adapting it to the unique realities of the Brazilian health system.

Anatomy of the Protocol: Flowcharts, Discriminators, and the Five-Level Color System

The MTS was created in Manchester, UK, in 1994 and has since become one of the most widely used triage systems in Europe and South America. In Brazil, it is the most frequently adopted protocol for risk classification. The system is designed to be a rapid, reproducible, and objective method for nurses to prioritize patients in crowded emergency departments.

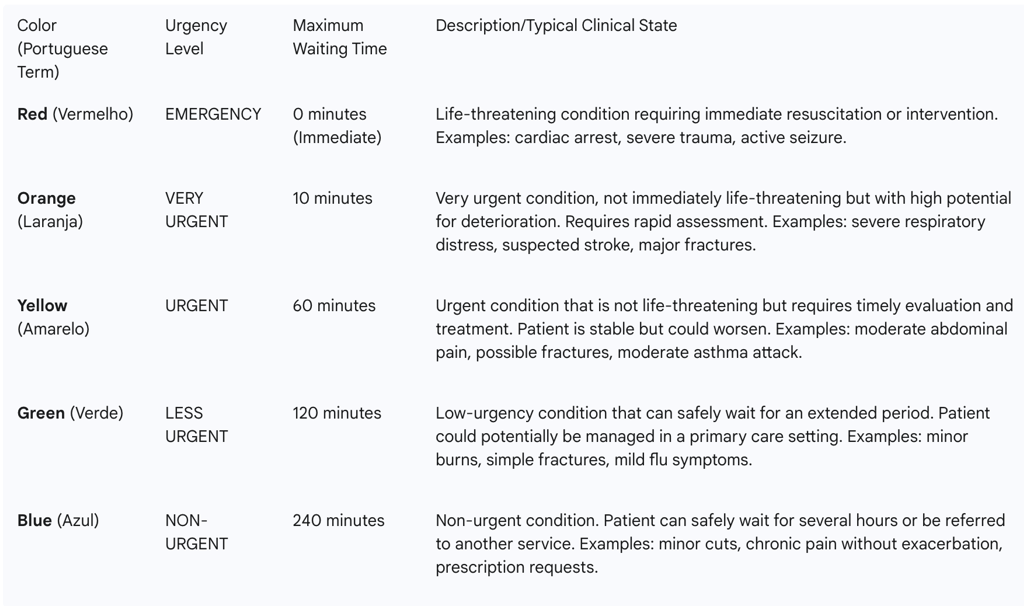

The process begins with the triage nurse identifying the patient's main complaint. Based on this complaint, the nurse selects one of 55 standardized "presentation flowcharts". Each flowchart contains a series of "discriminators"—specific clinical signs, symptoms, or historical facts presented in the form of questions—that guide the nurse's assessment. By working through the flowchart, the nurse determines the patient's clinical priority, which is assigned to one of five levels.

These levels are universally represented by a color-coded system, often communicated to the healthcare team via a colored wristband given to the patient. This visual cue allows for quick and unambiguous identification of patient priority. Each color corresponds to a specific level of urgency and a maximum target time within which the patient should receive a medical assessment.

The Brazilian Adaptation: Incorporating the "White" Category and Other Local Modifications

Brazil did not simply import the MTS wholesale; it adapted the protocol to better fit its specific systemic and epidemiological context. The most significant of these adaptations, shared with Portugal, is the inclusion of a sixth category: White (Branco). This category is reserved for patients who present to the emergency service for reasons unrelated to an acute clinical complaint. This includes individuals seeking to renew prescriptions, obtain medical certificates, or attend scheduled follow-up appointments or elective procedures that have been misdirected to the ED.

The creation of the "White" category is a highly strategic innovation. While it functions as a classification level, its primary purpose is administrative and diagnostic for the health system itself. It is explicitly designed to help identify and quantify "organizational dysfunction," particularly the inappropriate use of high-cost emergency services as a primary point of care. By systematically categorizing and counting these encounters, the system generates robust, quantifiable data on the proportion of ED demand that should be managed in primary care or other settings. This data provides hospital administrators and health policymakers with powerful evidence to advocate for strengthening primary care services and improving referral pathways, transforming anecdotal complaints about overcrowding into a measurable systemic problem.

Furthermore, the MTS has demonstrated its flexibility through adaptation to local epidemiological needs. For instance, to address the significant public health issue of venomous snake bites in Brazil, the standard MTS flowcharts were modified to incorporate specific discriminators related to different types of venom and their varying speeds and severities of action. This capacity for local tailoring, combined with its robust core structure, has been key to its successful dissemination across the country.

Case Study: Minas Gerais: Pioneering the Implementation of MTS and its Statewide Impact

The state of Minas Gerais, located in southeastern Brazil, played a pivotal role in the introduction and national dissemination of the Manchester Triage System. It acted as the gateway and testing ground for the protocol in Brazil. In 2007, a pioneering partnership was formed between the Minas Gerais State Health Secretariat (SES-MG) and the Portuguese Triage Group, which brought the MTS methodology to the country for the first time.

Crucially, the adoption in Minas Gerais was not a fragmented, hospital-by-hospital decision. Instead, the state government took a top-down approach, mandating the use of MTS as a required component of its statewide regionalization master plan for health services. This decisive policy action ensured widespread, standardized implementation and created a large cohort of professionals trained in the system. The success of this collaboration was so significant that the original creators of the MTS were later awarded a medal by the state government of Minas Gerais in recognition of their contribution.

This early, large-scale implementation had a profound national impact. It created a critical mass of experienced nurses and administrators who became experts in the protocol. Many of these professionals from Minas Gerais went on to form the core of the Grupo Brasileiro de Classificação de Risco (GBCR), the national organization now responsible for official MTS training and auditing across Brazil. In this way, Minas Gerais functioned as a "policy incubator." Its political will and strategic investment provided a proven implementation model, a trained workforce, and the institutional foundation (the GBCR) that were essential for the subsequent spread and standardization of the MTS across a country of continental dimensions. It was not merely an early adopter; it was the catalyst that made the national adoption of MTS feasible and successful.

A Federated System in Practice: Regional Variations in Triage Protocols

Brazil's Unified Health System (SUS) is constitutionally designed as a decentralized system, with responsibilities shared among federal, state, and municipal governments. While the Ministry of Health establishes national policies like the ACCR, the implementation is carried out by state and local health secretariats. This federated structure has led to a fascinating landscape of regional variations in triage protocols, where the national philosophy is adapted to meet local challenges and priorities.

The Distrito Federal: A Structured Approach to Protocol Adherence and Auditing

The Distrito Federal (DF), home to the national capital Brasília, has distinguished itself through a highly structured and formalized approach to triage management. The Health Secretariat of the Distrito Federal (SES-DF) has moved beyond simple implementation to a sophisticated system of governance and quality control, detailed in its comprehensive "Guia de Acolhimento e Auditoria" (Welcoming and Auditing Guide).

This guide, based on a 2018 manual, establishes a rigorous auditing process to ensure that triage practices conform to institutional protocols. Auditors use a checklist to verify the correctness of flowchart selection, discriminator application, and the final color-coded priority assigned to each patient. The SES-DF has also defined clear performance benchmarks, categorizing service efficiency as "Excellent" (conformity

≥ 95%), "Very Satisfactory" (85-94%), "Satisfactory" (70-84%), or "Unsatisfactory" (< 69%) based on audit results.

Furthermore, the DF has established target proportions for the distribution of triage classifications across its network (e.g., Red: 5%, Orange: 20%, Yellow: 40%, Green: 30%, Blue: 5%). This provides a statistical baseline to monitor patient acuity profiles, identify deviations, and manage patient flow across the system. This model represents a mature stage of policy implementation, shifting the focus from mere adoption to a continuous cycle of monitoring, measurement, and quality improvement. The DF's approach provides a powerful example of how to actively govern a triage system to ensure long-term fidelity and effectiveness.

Bahia and the Northeast: Implementing ACCR within Regional Health Networks

In the large and diverse state of Bahia, the implementation of ACCR has been strongly linked to the broader goal of strengthening and integrating regional health networks (Redes de Atenção à Saúde). The State Health Secretariat of Bahia (SESAB) developed a State Protocol for Risk Classification with the explicit aim of humanizing care and qualifying the entire network.

Municipal-level documents from across the state confirm that the ACCR process is guided by principles of qualified listening and adherence to directives from both the Ministry of Health and SESAB. A key feature of Bahia's approach is the effort to integrate ACCR with other network-based health programs. For example, ensuring that triage in maternity hospitals aligns with the principles of the

Rede Cegonha (Stork Network), a national program for improving maternal and infant care, is a stated priority. This "network-centric" philosophy emphasizes that the purpose of triage is not just to sort patients within one facility but to correctly direct them to the appropriate point of care within the larger regional system.

However, this ambitious goal faces significant hurdles. Reports have noted difficulties in the widespread and uniform implementation of the state protocol across all health units. This highlights a central tension within the SUS: the vision of fully integrated care networks often collides with the immense practical challenges of standardizing practices and building functional referral pathways across a vast and resource-varied territory. Bahia's experience underscores that a successful triage system depends not only on what happens at the front door of the emergency department but, crucially, on where that door leads.

Rio de Janeiro: Adapting Triage for a Complex Urban Health Environment

In the dense and complex metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro, the ACCR framework has been adapted to function primarily as a tool for regulation and high-stakes resource allocation. The intense operational pressures of a major urban center, with its often-fragmented network of public and private providers and demand that frequently outstrips supply, have shaped the local application of triage.

Documents from the State Health Secretariat of Rio de Janeiro (SES-RJ) emphasize risk classification as a necessity for organizing patient flow and establishing clear priorities in a crowded system. The focus often shifts to using triage protocols to make critical decisions about scarce resources, such as managing access to limited ICU beds during crises or determining priority for organ transplants. The language used in Rio de Janeiro's policy documents frequently centers on "regulação" (regulation) and managing patient flows between different units, reflecting the daily challenge of system navigation.

While the humanistic principles of ACCR are still present, their primary value in this context appears to be in providing a defensible, objective, and protocol-based framework for making difficult and often life-or-death resource allocation decisions. In a perpetually strained urban health system, triage becomes an essential mechanism for ensuring that the distribution of critical care resources is based on clinical need rather than other factors, thereby bringing a degree of equity and order to an otherwise overwhelming environment.

Synthesis of Regional Approaches: Identifying Common Principles and Divergent Practices

The examination of these diverse regional experiences reveals a consistent pattern: adherence to the national ACCR framework's core principles combined with significant local adaptation. Minas Gerais pioneered the technical implementation of a specific protocol (MTS). The Distrito Federal developed a sophisticated model of governance and quality control. Bahia has focused on using triage as a lever for network integration. Rio de Janeiro has leveraged it as a critical tool for regulation and resource management.

This variation should not be interpreted as policy fragmentation or failure. On the contrary, it is a clear demonstration of the SUS's foundational principle of decentralized governance in action. The national ACCR policy effectively provides the "what" (prioritize by risk) and the "why" (humanize care and ensure equity), while granting states and municipalities the autonomy to determine the "how" based on their unique epidemiological profiles, resource landscapes, and administrative capacities. This flexibility allows for the development of context-specific innovations and tailored solutions to vastly different local realities, showcasing the intended functionality of Brazil's federated health system. The diversity of approaches is a feature, not a bug, of the system.

Brazil in a Global Context: A Comparative Analysis of Triage Methodologies

To fully appreciate the nuances of Brazil's triage system, it is essential to position it within the international landscape of emergency care. By comparing the predominantly used Manchester Triage System with other globally recognized protocols, such as the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) and the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), the strategic choices underlying Brazil's approach become clearer.

Symptom-Based vs. Resource-Based Triage: Contrasting MTS with the Emergency Severity Index (ESI)

A fundamental divergence in triage philosophy is evident when comparing the MTS with the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), the dominant system in the United States. The MTS is a purely symptom-based system; acuity is determined by working through flowcharts of clinical signs and symptoms. In stark contrast, the ESI employs a hybrid model that, for less critical patients, becomes resource-based.

In the ESI algorithm, a nurse first assesses for immediate life-threatening conditions (Level 1) or high-risk situations (Level 2). If the patient is stable, the triage level (3, 4, or 5) is determined by the anticipated number of resources they will require to reach a disposition. Resources are defined as interventions like lab tests, imaging studies, IV fluids, or specialty consultations. A patient needing two or more resources is typically a Level 3, one resource is a Level 4, and no resources is a Level 5.

Studies evaluating the ESI's application in Brazil have highlighted significant challenges. A study using an adapted, non-validated version of the ESI found that nurses' accuracy in predicting resource use was low, with a Kappa coefficient of only 0.34. Another large-scale retrospective study in Porto Alegre found that even with rigorous training, a substantial number of patients were under- or over-triaged using ESI, with factors like advanced age and specific chief complaints being independent predictors of under-triage.

Brazil's clear preference for a symptom-based system like MTS over a resource-based one like ESI can be understood as a pragmatic adaptation to the realities of the SUS. The Brazilian health system is marked by significant regional inequalities in infrastructure and resource availability. A resource-based triage system is exceptionally difficult to standardize when the availability of those resources—such as a CT scanner or 24-hour laboratory services—can differ dramatically between a major university hospital in São Paulo and a rural emergency unit in the Amazon. A triage nurse in a resource-poor setting would be forced to conflate "needed resources" with "available resources," potentially leading to the systematic under-triage of patients. The MTS, by focusing exclusively on the patient's clinical presentation, provides a more portable and universally applicable standard of acuity that is independent of the immediate technological capacity of the facility. This makes it a far more equitable and appropriate choice for a heterogeneous national health system.

Evaluating Acuity and Modifiers: A comparison with the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS)

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) shares more methodological similarities with the MTS. It is also a five-level, color-coded, symptom-based system widely used in Canada and other countries. Both protocols are considered valid and reliable for general and pediatric populations.

However, there are important distinctions. The CTAS places a more explicit and structured emphasis on the use of "first- and second-order modifiers". These are objective physiological measurements—such as heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and temperature—and pain scale scores that can directly upgrade a patient's triage level, providing a more standardized way to account for abnormal vital signs. While MTS nurses certainly assess vital signs, the CTAS framework integrates them more formally into the final acuity decision.

Comparative analyses suggest that the CTAS may offer more detailed and robust guidelines for specific patient populations, such as pediatric and mental health patients, and a more structured approach to pain assessment. The MTS, on the other hand, is often highlighted for its highly structured flowchart and discriminator system, which is designed to minimize subjective judgment, and its strong integration with computer software for auditing and data collection.

International Lessons and Brazilian Innovations: Positioning Brazil's ACCR Framework Globally

This comparative analysis reveals that Brazil's approach to triage is a sophisticated "glocal" (global + local) model. By widely adopting the MTS, the country aligned its clinical practice with a proven, globally recognized standard, facilitating international comparison and ensuring a baseline level of safety and objectivity. This represents the "global" component of its strategy.

However, this global tool was not simply adopted; it was embedded within a uniquely Brazilian philosophical and policy framework—the ACCR under HumanizaSUS. This "local" framework, with its non-negotiable emphasis on Acolhimento (welcoming), qualified listening, and the humanization of the patient-provider encounter, addresses the specific social and systemic challenges of the SUS. Furthermore, the protocol itself was adapted to local realities, with the inclusion of the "White" category to diagnose systemic dysfunction and the modification of flowcharts for regional epidemiological threats like snake bites.

This combination is distinct from how triage is practiced elsewhere. The innovation of the Brazilian system lies not in the clinical sorting algorithm itself, but in the humanistic, systemic, and political wrapper within which it is placed. Brazil has taken a global best practice and infused it with its own national health philosophy, creating a model that seeks to be both clinically sound and socially just.

Efficacy, Challenges, and Outcomes: A Critical Evaluation of Triage in Brazil

The implementation of a nationwide triage policy is a monumental undertaking, and its real-world application is fraught with complexities. A critical evaluation of the ACCR framework and its associated protocols in Brazil reveals a mixed landscape of proven efficacy, significant performance gaps, and persistent systemic challenges that continue to test the resilience of the emergency care system.

Measuring Performance: Academic Insights into Protocol Validity, Reliability, and Accuracy

A substantial body of research has validated the fundamental premise of the triage systems used in Brazil. Studies consistently demonstrate that protocols like the MTS are good predictors of patient outcomes. There is a strong, statistically significant correlation between the assigned triage level and metrics such as the need for hospitalization, ICU admission, and mortality. Patients classified in the highest-priority categories (Red and Orange) have markedly higher rates of admission and death compared to those in lower-priority groups, confirming that the protocols are, at their core, successfully identifying the most critically ill patients.

However, this predictive validity is tempered by significant challenges in reliability and accuracy during day-to-day implementation. Studies assessing the inter-rater reliability of the MTS among Brazilian nurses have found it to range from "moderate" to "substantial," with performance being heavily influenced by the individual nurse's years of clinical experience. More concerning are findings from comprehensive evaluations of ACCR implementation, which have rated the quality of services in some hospitals as "Precarious". These evaluations point to a widespread failure to adhere to the foundational principles of the ACCR directive, such as providing adequate space for companions, consistently re-evaluating waiting patients, and ensuring the team has a deep understanding of the patient flow process.

This reveals a critical gap between a protocol's theoretical soundness and its on-the-ground fidelity. While the tools themselves are largely effective, their performance is heavily mediated by local, organizational factors, including the quality of professional training, the adequacy of physical infrastructure, and the strength of institutional support. The policy challenge, therefore, is not necessarily to find a "better" protocol, but to create the conditions under which the existing, validated protocols can be used effectively and consistently.

The Persistent Challenge of Overcrowding: The Role of Triage in Managing Inappropriate ED Utilization

Perhaps the single greatest challenge confronting emergency services in Brazil—and a major stressor on any triage system—is chronic overcrowding driven by a high volume of patients with low-complexity conditions. Research indicates that a significant percentage of patients seeking care in Brazilian emergency departments, sometimes estimated as high as 80%, are not true emergencies and could be appropriately managed in primary care settings.

This phenomenon stems from several factors, including weaknesses in the primary care network and a public perception that the ED is the most efficient and reliable gateway to the health system, offering faster access to specialists and diagnostic tests. This inappropriate utilization places an immense burden on emergency services, leading to long waiting times for all patients, contributing to professional burnout, and compromising the quality and safety of care.

In this context, the ACCR framework is forced to perform a function for which it was not primarily designed: acting as a de facto gatekeeper for the entire health system. The triage nurse must rapidly sift through a massive volume of low-acuity demand to identify the few critically ill patients hidden within the crowd. This is a reactive, defensive posture. It highlights the limits of what an intervention within the hospital walls can achieve when faced with a systemic failure in another part of the health network. The persistent overcrowding of Brazilian EDs is therefore not a failure of the triage protocol, but a clear symptom of a broader, unresolved challenge in the integration and capacity of the primary care system.

Impact on Patient Outcomes: Correlation between Triage Levels, Hospitalization, and Mortality

Despite the operational challenges, the data unequivocally shows that the implementation of risk classification has a positive impact on identifying and prioritizing critically ill patients. As noted, multiple Brazilian studies have established a direct and powerful correlation between higher triage acuity levels and more severe patient outcomes. One study found that patients classified in the high-priority group had hospitalization rates five times higher and mortality rates 10.6 times higher than those in low-priority groups. This demonstrates that the clinical logic of the protocols is sound and is being applied effectively enough to save lives by fast-tracking those most in need.

The strong predictive power of the triage classification has implications that extend beyond immediate patient care. The triage level assigned to a patient upon arrival is a powerful, real-time data point for both administrative management and public health surveillance. Hospital administrators can use the daily and hourly counts of patients in each color category to forecast demand for inpatient beds, ICU capacity, and staffing needs for the subsequent 24-48 hours. On a broader scale, public health officials can monitor triage data from across a city or region to detect emerging threats. A sudden, anomalous spike in high-acuity patients presenting with respiratory symptoms, for example, could serve as the earliest warning of a new influenza or viral outbreak, enabling a more rapid and targeted public health response. In this sense, the triage classification transcends its role in individual patient management and becomes a vital tool for real-time operational planning and epidemiological surveillance.

The Frontline Perspective: Challenges and Realities for Nursing Professionals in ACCR Implementation

Nurses are the linchpin of the ACCR system in Brazil. The responsibility for performing the risk classification falls squarely on them, a decision that has elevated their professional role and autonomy within the emergency department. However, this centrality has also exposed them to a unique and intense set of challenges.

Qualitative studies with Brazilian nurses reveal a consistent set of difficulties. They are on the front lines of managing the high patient demand and the public's frequent lack of understanding of the risk classification process, which can lead to verbal abuse and conflict with frustrated patients and families. They often find their clinical judgments undermined by subsequent delays in medical attention or a lack of available beds, forcing them to constantly re-evaluate waiting patients and manage the fallout from systemic bottlenecks. Furthermore, they report working in stressful environments with inadequate infrastructure, a lack of institutional support, and concerns for their own safety.

The implementation of ACCR has effectively transformed the triage nurse into a complex, hybrid professional who must act simultaneously as a rapid clinical assessor, an emotional shock absorber for systemic frustrations, a public educator, and a conflict mediator. This significant expansion of the nursing role is often not accompanied by commensurate investment in specialized training, institutional support, or security measures. The success of the entire triage system rests on the shoulders of these professionals, making their training, well-being, and empowerment a critical, yet often overlooked, leverage point for improving the entire emergency care process.

Strategic Recommendations for the Future of Triage in Brazil

The analysis of Brazil's triage landscape, from its philosophical underpinnings to its on-the-ground realities, points toward several strategic pathways for strengthening the system. The following recommendations are designed to address the key challenges identified in this report and to build upon the successes of the Acolhimento com Classificação de Risco framework.

Strengthening the Health Network: Integrating Emergency Triage with Primary Care to Alleviate Overcrowding

The most persistent threat to the efficacy of emergency triage is the overwhelming demand from patients with non-urgent conditions. Triage can manage this flow, but it cannot solve the underlying cause. Therefore, the highest-priority recommendation is to strengthen the integration between emergency services and the primary care network.

Co-locate Primary Care Services: Establish "fast-track" clinics or co-located primary care consultation rooms adjacent to or within emergency departments. Patients triaged as Green or Blue could be immediately directed to these services, providing appropriate care while decongesting the main ED.

Establish Formal Referral Protocols: Develop and enforce clear, bidirectional referral and counter-referral protocols between EDs and local Unidades Básicas de Saúde (UBS) or Equipes de Saúde da Família (ESF). This includes creating pathways for EDs to schedule next-day appointments at a patient's local UBS for follow-up, thereby ensuring continuity of care.

Invest in Primary Care Capacity: Ultimately, reducing inappropriate ED use requires a long-term investment in the capacity, accessibility, and perceived quality of primary care services to make them the preferred first point of contact for the population.

Enhancing Protocol Fidelity: Recommendations for Standardized Training, Auditing, and Continuous Quality Improvement

The gap between a protocol's proven validity and its variable implementation fidelity must be closed. This requires a systematic approach to quality governance, drawing on the model pioneered by the Distrito Federal.

Mandate National Certification: The Ministry of Health, in partnership with the Grupo Brasileiro de Classificação de Risco (GBCR), should develop a national certification program for triage nurses, requiring standardized training and periodic recertification.

Implement Systematic Auditing: State and municipal health secretariats should be required to implement regular, systematic audits of triage classifications, similar to the DF model. These audits should provide feedback to individual nurses and generate facility-level performance data.

Develop National Performance Benchmarks: The Ministry of Health should establish national performance benchmarks for key triage indicators (e.g., accuracy rates, time-to-triage, distribution of classifications) to allow for comparison and the identification of best practices and underperforming regions.

Public Health Communication: Strategies for Educating the Public on the Purpose and Function of Risk Classification

The conflict and dissatisfaction experienced by triage nurses often stem from a public misunderstanding of the triage process. A proactive public health communication strategy is needed to build trust and manage expectations.

In-Hospital Signage and Media: Develop clear, simple, and multilingual visual aids (posters, videos) for ED waiting rooms that explain the color-coded system, the concept of prioritization by risk, and estimated waiting times for each category.

Community-Based Campaigns: Launch public awareness campaigns through community health agents, schools, and media to educate the population on when to use primary care versus emergency services.

Standardized Communication Training: Incorporate communication and de-escalation techniques into the mandatory training for triage nurses to better equip them to manage difficult interactions with anxious patients and families.

Leveraging Technology: The Potential for Digital Health Tools to Optimize Triage Processes and Data Analysis

Technology can play a crucial role in improving the efficiency, consistency, and analytical power of the triage system.

Standardize Electronic Health Record (EHR) Integration: Promote the adoption of EHR systems that fully integrate the chosen triage protocol (e.g., MTS). This ensures that triage data is captured in a structured format, facilitates auditing, and prevents information loss.

Develop Real-Time Dashboards: Create dashboards for hospital managers and public health officials that visualize real-time triage data (e.g., number of patients by color, chief complaints, waiting times). This can support dynamic resource allocation and serve as an early warning system for public health emergencies, as discussed previously.

Explore Decision Support Systems: Investigate the potential of machine learning and AI-driven decision support tools that can analyze patient data (chief complaint, vital signs) and suggest a triage level to the nurse, potentially reducing variability and improving accuracy, particularly for less experienced professionals.

Adopting these interconnected strategies, Brazil can build upon the strong philosophical foundation of the ACCR framework, mitigate its operational challenges, and further solidify its position as a global leader in developing humanized, equitable, and effective emergency care systems.