The Belgian Triage System: Structure, Efficacy, and Future Directions

The Belgian emergency medical services (EMS) system operates under a complex, multi-layered framework, which, contrary to common assumptions, is not based on a single, universally applied triage system.

The Belgian emergency medical services (EMS) system operates under a complex, multi-layered framework, which, contrary to common assumptions, is not based on a single, universally applied triage system. While the pre-hospital emergency response is anchored by a standardized national protocol, the in-hospital triage environment remains a mosaic of local adaptations and experimental models. This report provides a detailed examination of this ecosystem, highlighting its core strengths, systemic challenges, and the empirical evidence that is driving calls for significant reform.

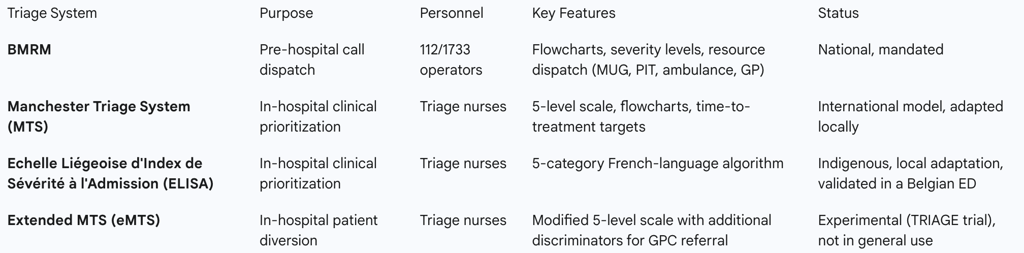

A key finding is the successful operation of a two-tiered pre-hospital system, utilizing the 112 emergency number for urgent cases and the 1733 number for non-urgent out-of-hours care. This is underpinned by the Belgian Medical Regulation Manual (BMRM), a national protocol that ensures a baseline level of uniformity and quality in the initial patient contact and resource dispatch. However, this centralized approach contrasts sharply with the decentralized nature of in-hospital triage. The widespread assumption that the Manchester Triage System (MTS) is a national standard is unsupported by available evidence; instead, it serves as a model for local, often experimental, adaptations.

This fragmentation contributes to significant systemic challenges, including chronic emergency department (ED) overcrowding, a high rate of non-urgent visits, and patient non-compliance with triage advice. Empirical studies on the 1733 system and nurse-led diversion trials reveal issues with classification accuracy and patient refusal, underscoring the limitations of voluntary systems. The COVID-19 pandemic inadvertently provided a compelling proof-of-concept for a potential solution through the rapid establishment of centrally coordinated triage and testing centers. This temporary model, which successfully diverted a substantial number of patients, has become a blueprint for professional organizations advocating for a permanent, mandatory pre-triage network.

Based on this analysis, several strategic recommendations are proposed to reconcile quality, accessibility, and affordability within the Belgian system. These include the formalization of a national in-hospital triage standard, the implementation of a binding pre-triage system to streamline patient flow, and continued investment in specialized training and digital infrastructure. Such reforms would shift the system from a responsive, fragmented state to a proactive, integrated, and more efficient model of care.

The Belgian EMS Ecosystem: Structure and Operation

2.1 The Two-Tiered Pre-Hospital System: 112 and 1733

Belgium's pre-hospital emergency care system is structured around two distinct, yet complementary, telephone channels. The primary emergency number, 112, is dedicated to urgent medical assistance, and calls are routed to one of 10 emergency centers located throughout the country. These centers are manned by hundreds of operators who analyze requests for assistance around the clock. The second channel, 1733, is a centralized number designed to provide access to non-urgent medical services, primarily for out-of-hours care on weeknights, weekends, and public holidays. This service is linked to local on-call medical services, and in many locations, calls are handled directly by the same 112 emergency centers, demonstrating a functional synergy between the two systems.

A core strength of this dual-channel approach is the ability of trained operators to triage callers using a shared manual. This allows them to refer individuals to the most suitable care option, whether it is an emergency ambulance or a general practitioner on-call. By serving as an initial point of contact and referral, this system aims to prevent unnecessary visits to EDs and to reduce the burden on general practitioners, thereby mitigating the risk of spreading infectious diseases like the COVID-19 virus.

2.2 The Belgian Medical Regulation Manual (BMRM): The Cornerstone of Pre-Hospital Triage

The lynchpin of Belgium’s pre-hospital medical coordination is the Belgian Medical Regulation Manual (BMRM). This guide provides an integrated set of medical protocols and flowcharts that are used by operators at both 112 and 1733 emergency centers. Its primary function is to uniformly determine the severity level of a caller's situation and, based on that assessment, to dispatch the most appropriate resources. These resources may include a Mobile Emergency Group (MUG/SMUR), a Paramedical Intervention Team (PIT), or an ambulance.

The existence of the BMRM establishes a centralized protocol for initial patient contact and resource allocation, creating a layer of uniformity that is not consistently present in subsequent stages of care. This top-down, standardized approach to pre-hospital triage ensures a baseline level of quality and care regardless of where the call originates. Its role is particularly critical during a crisis, as evidenced by the development of a temporary protocol during the coronavirus crisis, which was revised and updated in accordance with scientific knowledge to ensure efficient and effective handling of calls. This national-level consistency provides a robust backbone for the entire EMS system.

2.3 Human Resources and Legal Frameworks

The Belgian EMS system relies on a well-defined professional hierarchy. Emergency centers are staffed by operators who undergo a rigorous training program, including a basic course of 3 to 4 months followed by several months of on-the-job training. These operators are supported by a medical director, a deputy medical director, and nurse regulators. The medical director is an emergency doctor responsible for supervising the medical quality of the assistance provided, while the nurse regulator provides support and training to the operators. This structure, which includes specialized medical oversight for dispatch operators, is a critical component of quality assurance.

The legal and historical context of Belgian emergency medicine is equally important. The formal evolution of pre-hospital care can be traced back to the Belgian law on emergency medical services in 1964. This legislative foundation is significant because it was enacted during a period of considerable political and professional tension, namely a major doctors’ strike aimed at preventing increased state involvement in healthcare. This history of political and professional negotiation is deeply embedded in the system's structure and may help explain the ongoing fragmentation and resistance to top-down, binding reforms. The system's current form is a product of these negotiations, balancing public necessity with professional autonomy.

Hospital-Based Triage: Fragmentation and Local Adaptations

3.1 The Manchester Triage System (MTS): Widespread Use or Misconception?

The user query's premise regarding the widespread use of the Manchester Triage System (MTS) in Belgium requires clarification. It is essential to distinguish the clinical MTS, a 5-level framework for patient prioritization in emergency departments, from the financial trading platform, MTS S.p.A., which operates markets in Belgium and is authorized by the National Bank of Belgium. The MTS is a globally recognized system that categorizes patients into five priority levels: Red (Immediate), Orange (Very Urgent), Yellow (Urgent), Green (Standard), and Blue (Non-Urgent).

Despite its global application, the evidence does not support the notion that MTS is a national standard in Belgium. In fact, one study on MTS performance in Rotterdam and Lisbon explicitly states that it has no information on Belgian implementation. While some Belgian EDs may have adopted nurse-led triage, this process was historically experimental in its ability to divert patients to other services. The TRIAGE trial, a single-center study on patient diversion, utilized an

extended version of MTS, which was a specific research adaptation rather than a standard clinical tool. This suggests that rather than a universally mandated system, MTS and similar international models serve as inspiration or the basis for local adaptations, contributing to a fragmented in-hospital triage landscape.

3.2 Alternative and Indigenous Triage Scales

The decentralized nature of Belgian hospital triage is further exemplified by the development and use of indigenous scales. For instance, the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) has been assessed in a Belgian hospital, with a study revealing suboptimal interrater agreement for triage levels, despite a locally developed training program. This indicates that simply importing a foreign model without significant adaptation may not be sufficient for the Belgian context.

A more telling example is the Echelle Liégeoise d'Index de Sévérité à l'Admission (ELISA), a French-language, five-category nursing triage algorithm developed in Liège. This scale was created specifically to address overcrowding in a local ED, demonstrating the need for a system tailored to the unique characteristics of the regional emergency medical services. The development of such a scale and the active lobbying by professional organizations like the Francophone Association of Emergency Nurses (AFIU) for a common national standard illustrate a clear desire among clinicians for a system that is culturally and professionally relevant to Belgium's unique bilingual context and its fragmented healthcare structure.

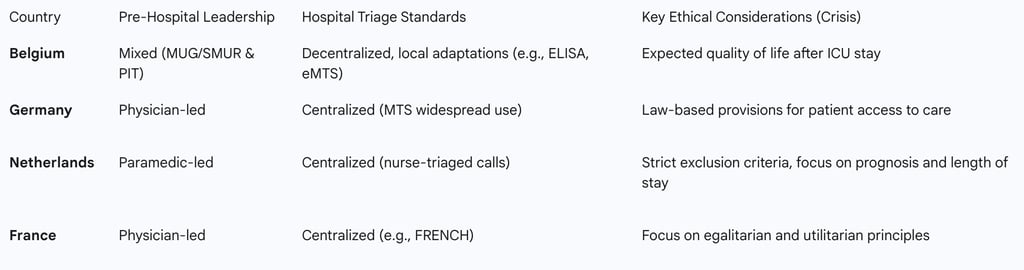

Table 1: Belgian Medical Triage Frameworks

Critical Analysis: Systemic Challenges and Empirical Efficacy

4.1 The Overcrowding Problem and Inappropriate Use of EDs

A significant challenge facing the Belgian emergency care system is chronic overcrowding in emergency departments, which is often attributed to the inappropriate use of services. A substantial proportion of patients, estimated at 40-56%, present at EDs with non-urgent problems that are not in direct need of hospital care. A key contributing factor to this phenomenon is the lack of a "gatekeeper model," which allows patients to access all levels of the healthcare system, including EDs, without a referral from a general practitioner. This open access, combined with patient preferences for the convenience of out-of-hours care and the availability of a full range of services at any time, leads to a high volume of non-critical visits that strain hospital resources.

4.2 Empirical Efficacy of Triage and Patient Diversion

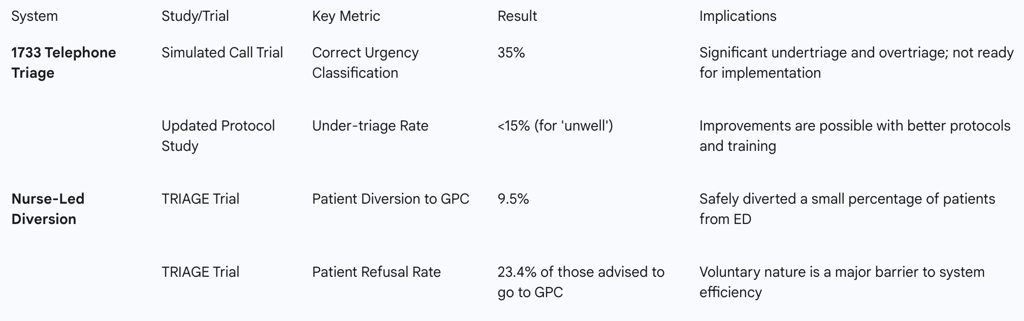

Two key studies provide empirical data on the efficacy of Belgian triage and diversion efforts. An analysis of the 1733 telephone triage system for non-urgent care revealed that in its early development phase, operators chose the correct urgency level in only one out of three cases, with under- and over-triage rates of 26% and 39% respectively in simulated trials. While a later study showed improvements with better protocols and training, it noted that issues such as "failure to recognize keywords" and a lack of operator experience remained as significant barriers to accurate classification.

In an attempt to address ED overcrowding directly, the TRIAGE trial tested a nurse-led diversion system in a single hospital, where low-risk patients were advised to visit an adjacent general practitioner cooperative (GPC). The study found that while the system was safe, with a 9.5% patient diversion rate, a significant portion of patients (23.4%) who were advised to go to the GPC refused and chose to remain in the ED. This high refusal rate highlights a critical limitation of a voluntary system.

4.3 The Phenomenon of Non-Compliance

The high rate of patient non-compliance is a major professional and policy challenge. The TRIAGE trial identified that factors such as being male, not living nearby, and the time of day (more refusals in the evening) influenced a patient’s decision to ignore triage advice. This behavior is a direct manifestation of the voluntary nature of the current system, where patients can bypass a triage assessment simply by ignoring the recommendation.

Professional organizations are acutely aware of this challenge and are advocating for a fundamental policy shift. The chair of Wachtposten Vlaanderen, for instance, has stated, "We cannot refuse a patient if they ignore the advice to wait... We want to make that binding so that we can all shorten the waiting times". This demonstrates a clear cause-and-effect relationship, where the empirical evidence of patient non-compliance is driving a strategic push for a legal or structural change that would formalize the pre-triage process and prevent patients from circumventing it.

Table 2: Empirical Efficacy of Triage Systems

A Case Study in Adaptation: The COVID-19 Triage Centers

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a pivotal moment for Belgian emergency medical care, providing a real-world case study for a national-level triage and diversion system. In response to the crisis, the government established temporary triage and testing centers, organized and coordinated by general practitioner groups. These centers were set up at a rate of one per 100,000 inhabitants, with the explicit goal of preventing emergency departments and general practitioners from being overwhelmed by a high volume of potentially infected patients.

The dual function of these centers—triage by a doctor to determine the need for ED referral, and testing to meet population screening needs—proved to be highly effective. This model succeeded by centralizing coordination and establishing a clear, dedicated pathway for a specific patient cohort. The temporary system, with its centralized oversight and decentralized operation, provides a compelling blueprint for a permanent, national pre-triage network. It demonstrated that a formal, coordinated, and medically-supervised pre-triage system can effectively divert non-critical patients and reduce the burden on acute care facilities, offering a viable solution to the chronic challenges of fragmentation and overcrowding.

The Human Element: Training, Quality, and Professional Advocacy

The operational effectiveness of the Belgian triage system is deeply dependent on the expertise of its professional staff. As detailed in a master plan for 112 emergency centers, the system is guided by several issues, including human resources, organization of work, and tools and technology. For example, 112 operators receive a comprehensive training regimen that includes several months of on-the-job training in a supervised environment. Moreover, the medical directorates, comprised of specialized emergency doctors, and nurse regulators are present in the emergency centers to support and advise operators, ensuring quality control.

A growing push for a common national triage scale is being championed by professional bodies such as the Francophone Association of Emergency Nurses (AFIU) and the Flemish Association of Intensive Care Nurses (VVVS). These organizations recognize that a standardized approach is essential for enhancing patient care and improving the efficiency of emergency services. This professional advocacy is a significant driver of change and is not solely a clinical aspiration; it is also a professional one, with organizations lobbying for financial recognition for the intellectual work of triage nursing. This indicates that future reforms are likely to be driven from the ground up by the very professionals who operate the system. Furthermore, studies on nurse workload have found that each additional patient increases nursing care time by 45 minutes, explaining 78% of workload variation, a factor that a centralized triage system could help mitigate.

International Context: A Comparative Perspective

7.1 Triage Philosophy: Belgium vs. its Neighbors

A comparative analysis provides valuable context for the Belgian triage system. Across Europe, pre-hospital EMS models vary, with French and German ambulance services being "physician-led," while Dutch and British systems are more "paramedic-led". Belgium's model represents a "mixed" approach, as its Mobile Emergency Group (MUG/SMUR) teams, which provide advanced life support, consist of both a doctor and a specialized nurse and are always dispatched with an ambulance. This integration of both paramedic and physician-led teams positions Belgium as having a unique operational philosophy.

7.2 Ethical Dimensions of Triage in MCIs

An analysis of ethical triage guidelines for mass casualty incidents (MCIs) and crisis situations reveals a distinct philosophical approach in Belgium. In a review of ICU triage guidelines during a pandemic, Belgian documents were found to recommend taking into account the "expected quality of life" of patients after their release from the ICU. This is a profound ethical departure from other nations, such as Canada, which advises against such considerations due to time constraints and a focus on maximizing the number of life-years saved. This finding suggests that Belgium’s triage protocols are not solely utilitarian but also incorporate a more holistic, patient-centered ethical framework, a key point of differentiation from more purely quantitative models in other nations.

Table 3: International EMS System Comparison

Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

8.1 A Synthesis of Findings

The Belgian triage system is a patchwork of protocols, not a single standard. It is characterized by a robust, national pre-hospital backbone (the BMRM) that provides a consistent framework for dispatch, but this is followed by a fragmented and inconsistent in-hospital environment. Chronic ED overcrowding, the high volume of non-urgent visits, and patient non-compliance with advice are key drivers of inefficiency. The TRIAGE trial and other studies have confirmed that a voluntary system is insufficient to address these challenges. However, the temporary COVID-19 triage centers demonstrated the feasibility and success of a centrally coordinated, decentralized pre-triage network. The push for a standardized national scale from professional organizations further indicates a critical inflection point for the system.

8.2 Actionable Recommendations

Based on this comprehensive analysis, the following strategic recommendations are put forth to enhance the efficiency, safety, and coherence of the Belgian triage system:

Formalize a National Triage Framework: The Federal Public Service (FPS) Public Health should establish a binding, national standard for in-hospital triage. This framework should draw on the empirical successes of local and indigenous models like the ELISA scale, ensuring it is tailored to the Belgian context while upholding international best practices.

Implement a Mandatory Pre-Triage System: A permanent, centrally coordinated pre-triage network should be established, utilizing phone, application-based, or in-person channels. This system would serve as a formal "gatekeeper," directing patients to the most appropriate care setting—a general practitioner, a walk-in clinic, or the emergency department—before they arrive at a hospital. Making this system legally binding would address the issue of patient non-compliance and rationalize patient flow.

Enhance Professional Training and Standardization: The BMRM should be regularly updated to address lingering issues, such as the "unclear problem" protocol, and to incorporate lessons learned from recent trials. Continuous, hands-on training for operators and triage nurses is essential to improve classification accuracy and reduce errors. The professional associations' call for a common national scale and the financial valuation of triage work should be supported to empower and incentivize the healthcare professionals who are critical to the system’s success.

Invest in Digital Integration and Research: Policymakers should allocate resources for the development of an integrated, digitized platform. This platform would not only support the new pre-triage system but also enable real-time tracking of patient flow, resource utilization, and triage outcomes, providing the empirical data necessary for continuous evidence-based policy and quality improvement.