Swedish Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (SweTRISS)

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the Swedish Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (SweTRISS), commonly known as RETTS (Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System) or formerly METTS (Medical Emergency Triage and Treatment System). Developed to standardize and optimize patient assessment and prioritization across various emergency care settings in Sweden and other Nordic countries, RETTS has become a cornerstone of emergency medical services. The system's core strength lies in its structured approach, combining objective Vital Signs (VS) with comprehensive Emergency Symptoms and Signs (ESS) to assign a medical urgency level. Its widespread adoption, reaching nearly all Swedish Emergency Departments (EDs) by 2010, underscores its perceived value in improving patient flow and consistency in decision-making.

However, the report also delves into critical considerations and challenges. While RETTS has demonstrated effectiveness in identifying time-sensitive conditions and reducing mortality risk for low-acuity patients, a significant concern is its tendency towards over-prioritization, particularly at the "orange" and "yellow" triage levels. This over-triage can contribute to ED crowding, inefficient resource allocation, and potentially increased waiting times for truly critical patients. The emergence of alternative systems like WEST (WEst coast System for Triage), specifically designed to mitigate this over-prioritization, highlights a recognized need for calibration and refinement within the Swedish triage landscape. Furthermore, a notable gap exists in high-quality, comprehensive academic studies validating RETTS's long-term reliability, validity, and direct impact on patient waiting times, despite its extensive use.

Looking forward, the continuous evolution of SweTRISS will necessitate leveraging technological advancements, such as AI and digital simulation, to enhance workflow efficiency and patient safety. Addressing the over-prioritization issue through algorithmic refinement and robust clinical judgment integration, potentially drawing lessons from WEST, will be crucial. Strengthening the evidence base through rigorous, multi-center research and ensuring comprehensive, ongoing professional training are paramount for SweTRISS to maintain its critical role in delivering high-quality, equitable, and efficient emergency care in Sweden.

Introduction to Emergency Triage in Sweden

1.1. The Imperative of Triage in Modern Emergency Healthcare

Emergency departments (EDs) globally face escalating patient volumes and increasing complexity of cases, which necessitates the implementation of robust triage systems to effectively prioritize patient care and optimize the allocation of scarce resources. Triage, a practice with historical roots in military medicine dating back to the 18th century, has undergone significant evolution to become a fundamental component of modern civilian emergency medicine. Its primary objective is to direct patients to the appropriate care provider and level of care in a timely manner, ensuring that those with the most urgent conditions receive immediate attention. This systematic approach to patient sorting is vital for preserving human life and health, particularly in light of the growing disparity between healthcare needs and available resources in emergency settings. The historical progression of triage from battlefield necessity to a civilian healthcare cornerstone underscores a universal recognition of the need for systematic prioritization when resources are constrained. In the contemporary healthcare environment, this imperative is amplified by persistently high demand, making efficient triage not merely a clinical tool but a critical operational and public health strategy.

1.2. Context of the Swedish Healthcare System and its Approach to Emergency Care

The Swedish healthcare system is widely recognized for its distinctive approach, characterized by a non-hierarchic, team-based, patient-centered, and value-driven model of care. This framework consistently yields excellent results, with Sweden's healthcare system ranking highly, notably fourth best globally among 195 countries in one comprehensive study. A foundational aspect of this system is its predominantly tax-funded structure, which is designed to ensure equality, safety, reliability, and efficiency in healthcare provision, thereby guaranteeing access to subsidized care for all citizens. Public funding accounts for a substantial 86% of the nation's total health and medical costs. This strong public funding and emphasis on equality in Swedish healthcare suggest a systemic drive to ensure that patient prioritization systems, such as RETTS, are applied uniformly and equitably across the entire population, irrespective of socioeconomic status. This stands in contrast to systems where financial or insurance status might implicitly influence access or the speed of care, as the Swedish model's financial structure inherently removes such variables, leading to triage decisions based purely on medical need and fostering a more equitable application of the system.

Furthermore, Sweden's long-standing use of national quality registries and a social security number system for over 70 years has established a robust infrastructure for extensive data collection. This capability is leveraged for continuous learning, improvement initiatives, and research, all contributing to enhanced healthcare outcomes. The robust national quality registries and extensive history of data collection indicate a strong underlying infrastructure for evaluating and continuously refining healthcare interventions, including triage systems. This environment should, in theory, facilitate more sophisticated analyses of RETTS's performance and enable evidence-based adjustments, even if some current studies on RETTS's comprehensive validity are noted as requiring further depth. The capacity for robust research is therefore well-established, paving the way for future data-driven improvements.

1.3. Evolution of Triage Systems in Swedish Emergency Departments

The development of emergency department triage in Scandinavia, including Sweden, is a relatively recent undertaking, gaining significant attention from the late 1990s onwards. A national survey conducted in 2000 revealed that approximately half of Swedish hospitals had implemented Registered Nurse (RN)-led triage, with a considerable number planning to introduce written guidelines to enhance competency in triage practices.

A period of rapid acceleration in the adoption of triage scales occurred between 2009 and 2010, during which the proportion of Swedish EDs utilizing a triage system surged from 73% to 97%. This swift increase was accompanied by a notable reduction in the diversity of triage scales in use, decreasing from 54 to just 10, thereby establishing a more standardized platform for triage across the country. This rapid and near-universal adoption of triage systems, and the standardization of those systems within a short timeframe, suggests a strong national impetus and a highly coordinated effort to address challenges such as emergency department crowding and to improve overall patient flow. This indicates a strategic, systemic approach rather than fragmented, isolated initiatives.

This period of development led to the emergence of two prominent new Swedish triage scales: the Adaptive Process Triage (ADAPT) and the Medical Emergency Triage and Treatment System (METTS). Both of these systems were designed with integrated logistic components specifically aimed at improving patient flows within emergency settings.

Core Principles and Operational Mechanics of RETTS

2.1. Foundational Principles and Objectives of the System

The Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (RETTS) functions as a comprehensive decision support system, specifically engineered to assist healthcare professionals across a diverse array of care environments. These settings include primary care facilities, ambulance services, and emergency departments. The system has been in continuous operation for over a decade throughout Nordic countries, accumulating a vast dataset of more than 60 million patient assessments.

RETTS is built upon several core objectives: to foster consistent decision-making among clinicians, to facilitate faster action in critical situations, and to ensure its continuous evolution through regular updates based on the latest research and clinical guidelines. The system's design mandates a systematic and structured approach to triage, ensuring that every healthcare professional adheres to the same robust criteria when evaluating the severity of a patient's condition. This commitment to consistency is paramount for enhancing communication channels and standardizing the flow of vital information across the entire emergency care continuum.

A fundamental principle guiding RETTS is that patient prioritization is determined exclusively by the patient's medical risk and immediate need. The system explicitly states that this prioritization is "unrelated to the order of care or time to doctor, X-ray, or other interventions". Instead, it provides clear recommendations for immediate actions and outlines logistical considerations, guiding the management of care processes from a medical safety perspective. The strong emphasis on "consistency" and "standardization" in RETTS's design suggests that its development went beyond merely creating a clinical tool; it was conceived as a system-level intervention aimed at reducing variability in care, improving inter-professional communication, and enhancing overall system efficiency. This aligns seamlessly with the broader objectives of the Swedish healthcare system, which prioritizes equality and reliability in its service delivery.

2.2. Key Components for Patient Assessment

RETTS employs a dual-factor approach to support emergency assessments, relying on two highly reliable sets of data:

Vital Signs (VS): This component is rooted in the widely recognized ABCDE principle and involves the objective measurement of physiological parameters. These include heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, body temperature, and oxygen saturation.

Emergency Symptoms and Signs (ESS): This element comprises structured sets of clinical findings, presented as "ESS cards." These cards are systematically utilized to ascertain a patient's condition. Each ESS card is comprehensive, offering guidance on how to test, monitor, and manage patients, thereby aiming to streamline decision-making processes and reduce the time clinicians spend on determining appropriate actions.

The operational mechanics of RETTS involve combining these two critical factors. The system then selects the factor that indicates the shortest "time-to-doctor," providing a more complete and consistent overall assessment of the patient's condition. This integrated approach is represented visually by a series of color-coded cards, ranging from blue to red, guiding users through a three-step process: assess vital signs, consult ESS cards, and then combine the information to determine the highest urgency level, enabling secure triage decisions. The dual-factor approach (VS + ESS) represents a sophisticated design choice that seeks to overcome the limitations inherent in relying solely on objective physiological data or subjective symptom reporting. This methodology is intended to capture both acute physiological instability and potential underlying serious conditions, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy and patient safety by proactively reducing the likelihood of under-triage. Indeed, the system's design explicitly accounts for the fact that approximately 45% of patients are at risk of being under-triaged if only vital signs were considered, emphasizing that factoring in ESS helps decision-makers identify otherwise undetected problems and prevent delays in care.

2.3. RETTS Triage Levels and Color-Coding System

RETTS utilizes a five-level, color-coded classification system to denote increasing order of priority and severity. These levels are indicative of the patient's risk of death and/or the immediate need for emergency care. Beyond mere prioritization, these levels also provide specific recommendations for patient management, including the intensity of monitoring required and the degree of proximity and supervision necessary from healthcare personnel.

The five process levels are:

Red (Immediate/Critical): This is the highest priority level, signifying an immediate life threat. Patients classified as Red require "emergency care immediately." Clinical examples include individuals exhibiting signs of airway obstruction or those who are unconscious (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) <8, Reaction Level Scale (RLS) >3, or P&U in ACVPU). Observations indicate that patients triaged to the Red level in RETTS include those who subsequently died within 72 hours.

Orange (Potential Life Threat/Very Urgent): This level indicates a potential life threat, also mandating "emergency care immediately". It represents the second-highest priority within the RETTS framework.

Yellow (Urgent but Stable): Patients in this category are classified as not life-threatening but require emergency care within a reasonable timeframe, meaning they "can wait" without apparent medical risk. Studies have shown that patients triaged to the Yellow level (along with Green) had a significantly lower risk of death, specifically 79-100% lower risk within the first 48 hours.

Green (Minor/Ambulatory): This level denotes minor, non-life-threatening injuries, often assigned to ambulatory patients. Similar to Yellow, patients triaged to Green had a 79-100% lower risk of death in the first 48 hours, with no observed risk of death within 48 hours for those assigned to this lowest level. These patients can frequently be managed at a lower level of care, potentially in collaboration with primary care services.

Blue (Non-Urgent): This category is for patients with a very limited acute need for emergency care at the time of presentation. They typically have minor medical problems that can sometimes be resolved through a simple healthcare intervention or by direct referral to another level of care.

The explicit statement that RETTS prioritization is "unrelated to the order of care or time to doctor" signifies a deliberate philosophical stance: triage determines medical risk, not necessarily queue position. However, this creates a tension with patient expectations and operational realities, as long waiting times are a known problem in Swedish EDs. This separation of medical risk assessment from explicit waiting time guidance could be a contributing factor to patient frustration and perceived inefficiency, especially if patients are "ignorant about, or do not understand why they are waiting".

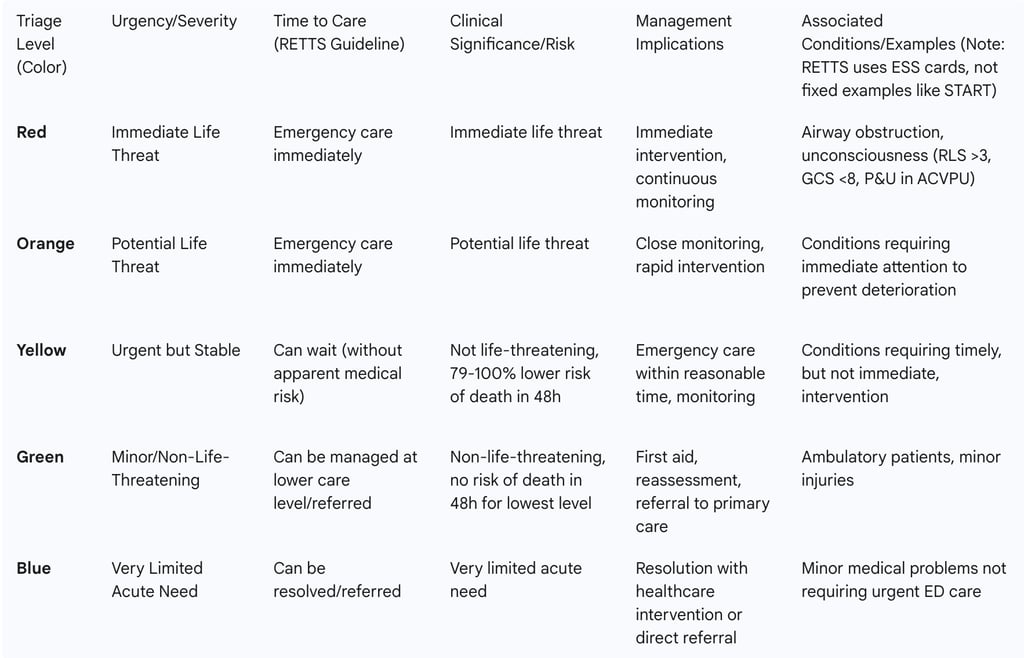

Table 1: RETTS Triage Levels, Clinical Urgency, and Management Implications

Historical Trajectory and Widespread Adoption of RETTS in Sweden

3.1. Genesis and Development of RETTS (formerly METTS)

The Medical Emergency Triage and Treatment System (METTS), which later became known as the Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (RETTS), emerged as one of two significant new triage scales developed in Sweden. Its counterpart, Adaptive Process Triage (ADAPT), also shared the common goal of improving patient flows within emergency settings. A key aspect of RETTS's lineage is its development from the Manchester Triage Scale (MTS). However, the specific methodological details of how this development transpired are not extensively documented in the available information. This evolution from MTS suggests that RETTS likely incorporated or adapted core principles from a widely recognized international triage system, subsequently customizing them to align with the specific needs and operational context of the Swedish healthcare environment. The absence of detailed information regarding this developmental process represents a gap in fully understanding the precise adaptations and their underlying rationale. The system has been in continuous use for over a decade across Nordic countries, demonstrating its sustained relevance and utility. The name change from METTS to RETTS is acknowledged in academic literature, reflecting its ongoing evolution.

3.2. National Implementation and Prevalence Across Swedish Emergency Departments

RETTS, under its former designation METTS, rapidly became the most commonly implemented triage scale throughout Sweden in both 2009 and 2010. By 2010, a significant proportion—nearly two-thirds (65%)—of all Swedish emergency departments had adopted METTS. This widespread adoption was part of a broader national trend in which the percentage of EDs utilizing a triage scale dramatically increased from 73% in 2009 to 97% in 2010. This period also saw a substantial reduction in the number of different triage scales employed nationally, fostering a more unified and common platform for emergency care assessment. The rapid and near-universal adoption of RETTS (as METTS) within a single year (2009-2010) points to a highly centralized or strongly coordinated healthcare system, demonstrating its capacity for swift policy implementation. This level of harmonization represents a significant operational achievement, facilitating a "common language for clinicians" and potentially streamlining inter-hospital transfers and national data collection efforts. The dominance of METTS/RETTS in Sweden is largely attributed to existing collaborative efforts aimed at continuous improvement and proactive promotion by its developers.

3.3. Training, Education, and Certification for Healthcare Professionals

Predicare, the company responsible for RETTS, plays a crucial role in its widespread adoption and consistent application by providing comprehensive training and education. This training is included as part of every RETTS license at no additional cost. The training program is delivered through a flexible e-learning platform, enabling medical staff to learn at their own pace and convenience. This is further supplemented by support from local trainers who offer both in-person and online sessions. RETTS is specifically designed to be "easy for trained medical staff to learn and understand," which contributes significantly to its reliable utilization across diverse medical fields and promotes consistency in decision-making processes. The provision of free and flexible training by the vendor is a critical factor in facilitating widespread adoption and consistent application of RETTS. This approach effectively reduces barriers to entry for healthcare providers and ensures a baseline level of competency, directly supporting the system's objective of consistent decision-making.

Furthermore, Predicare is actively involved in efforts to obtain CE (Conformité Européenne) marking for "RETTS Plus," which signifies ongoing commitment to regulatory compliance and development of the software as a medical device. This process entails the establishment of a digital quality management system, the creation of steering documents for software development and risk management, and the implementation of robust market feedback mechanisms. The pursuit of CE marking for "RETTS Plus" indicates a commitment to formal regulatory compliance and quality assurance for the software as a medical device. This implies a recognition of the system's critical role in patient care and the necessity for robust governance, signifying a shift beyond mere "decision support" to a regulated medical tool.

Impact of RETTS on Emergency Department Operations and Patient Outcomes

4.1. Effectiveness in Patient Assessment and Prioritization

RETTS is a key tool utilized by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) nurses for pre-hospital patient assessment, with its performance rigorously evaluated in large cohorts of both children and adults. In the context of adult patients, the EMS nurse's field assessment using RETTS was deemed appropriate in 82% of cases when compared against final hospital diagnoses. This demonstrates a high degree of concordance between initial triage and definitive medical diagnosis.

When compared to the National Early Warning Score (NEWS), RETTS for adults exhibited a greater probability of detecting time-sensitive conditions. However, this came at the cost of lower specificity. This characteristic suggests that RETTS possesses a higher sensitivity for identifying critical conditions, meaning it is more likely to correctly identify patients who truly have a time-sensitive issue. While RETTS shows good performance in identifying low-risk patients and detecting time-sensitive conditions (high sensitivity), its lower specificity compared to NEWS suggests a tendency towards over-triage. This trade-off is often inherent in triage systems that prioritize patient safety (minimizing false negatives) over resource efficiency (minimizing false positives).

Patients triaged to the lowest urgency levels, specifically green or yellow, demonstrated a significantly reduced risk of death, with a 79-100% lower risk within the first 48 hours. Notably, for those triaged to the green level, there was no observed risk of death within 48 hours. This finding indicates a strong discriminatory ability for low-risk patients, allowing for confident management at lower care levels. A study analyzing different editions of RETTS© (2013 and 2016) further revealed a statistically significant difference in 10-day mortality risk and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission rates across various triage levels, with higher risks consistently observed for patients assigned higher acuity levels compared to those in the green category. However, the study found no statistically significant impact on 10-day mortality when comparing the two annual editions of RETTS©, suggesting stability in its core predictive power over time.

4.2. Influence on Patient Safety and Management of Waiting Times

Long waiting times remain a persistent and significant challenge within the Swedish healthcare system, characterized by substantial variations across different regions and various healthcare sectors. A recent Swedish study highlighted this issue, indicating that 38% of emergency department patients experience waits exceeding four hours, with older patients typically enduring the longest delays. Such prolonged waiting periods can critically compromise patient safety and profoundly diminish the overall patient experience. Emergency department staff are acutely aware of this problem and are actively concerned with strategies to reduce waiting times.

RETTS is designed with the aim of enhancing efficiency, improving patient handovers between care providers, facilitating more effective resource allocation, and fostering patient confidence through the delivery of consistent care. The system is intended to assist healthcare professionals in determining which patients require more immediate treatment, guiding appropriate monitoring and treatment protocols, alleviating staff stress, and ultimately improving patient flows within the emergency department.

However, a notable characteristic of RETTS is that while it specifies levels of medical availability—categorizing patients as requiring "emergency care immediately" or being able to "can wait"—it does not provide explicit recommended waiting times in minutes for any given priority level. The disconnect between RETTS's focus on medical risk prioritization (without explicit waiting times) and the documented problem of long waiting times suggests that while RETTS may effectively categorize urgency, it does not inherently resolve the systemic issues of ED capacity and patient flow. This indicates that triage is a necessary but insufficient condition for optimal ED performance. Patient perceptions of waiting times are significantly influenced by their health concerns, their expectations for a rapid visit, and their understanding of the reasons behind any delays. Waiting is often deemed "non-acceptable" if no progress is apparent or if patients are left uninformed about the rationale for their wait. The psychological impact of waiting, particularly when patients are "confused" or "ignorant about... why they are waiting" , points to a gap in patient communication and transparency within the emergency department process. Even with an effective triage system, the patient experience can be severely negative if expectations are mismanaged or information is withheld.

4.3. Diagnostic Accuracy: Under-triage and Over-triage Rates

The accuracy of a triage system is commonly evaluated through its rates of under-triage and over-triage. Under-triage occurs when seriously injured patients are transported to non-trauma hospitals or are assigned a priority level lower than the established gold standard, representing a false negative rate (1-sensitivity). Conversely,

over-triage is defined as the assignment of a priority level higher than the gold standard to non-injured patients, leading to unnecessary resource utilization (a false positive rate, 1-specificity).

For EMS triage in adults utilizing RETTS, observed under-triage rates were 19%, while over-triage rates stood at 36%. In the pediatric population, EMS triage with RETTS showed an under-triage rate of 33% and an over-triage rate of 33%. Another study, which compared RETTS-A (adults) with a "Medical Index," reported an over-triage rate of 28.6% and an under-triage rate of 23.4% for RETTS-A. Generally, acceptable under-triage rates are considered to range from 1% to 10%, while acceptable over-triage rates fall between 25% and 50%.

A significant concern that has emerged over time pertains to RETTS's tendency towards over-prioritization. Specifically, at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden, the proportion of patients triaged to the second-highest level, "orange," increased from 14% in earlier reports to 20-27% by 2018. This consistent and increasing trend of over-prioritization in RETTS suggests a potential "triage creep" phenomenon, where the threshold for higher urgency levels gradually lowers over time. This could be influenced by various factors, including a safety-first bias among clinicians, a lack of clear feedback mechanisms regarding over-triage rates, or a natural response to increasing pressures within the emergency department.

This over-prioritization creates substantial challenges in accurately identifying truly high-risk patients within the larger pool of "urgent" cases. It directly contributes to increased waiting times for genuinely critical patients and exacerbates emergency department crowding, which in turn negatively impacts the working environment for emergency staff. For instance, a study revealed that approximately 55% of patients triaged to the "orange" level in RETTS were ultimately discharged home, indicating a considerable degree of over-triage at this particular level.

5. Comparative Analysis: RETTS Versus Other Triage Systems

5.1. Overview of Prominent International Triage Systems

The landscape of emergency triage systems is diverse, with several prominent models employed globally, each with its unique methodology and strengths.

Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment (START): This system is primarily used by first responders to rapidly sort patients in mass casualty incidents or high-pressure environments. It categorizes patients based on the extent of their injuries using a color-coded tag system: Red for immediate/critical, Yellow for delayed/urgent, Green for minor/ambulatory, and Black for deceased. The START algorithm involves a quick, sequential assessment, typically completed within 60 seconds. It evaluates a patient's ability to walk, spontaneous breathing (and airway opening if absent), respiratory rate (above or below 30 breaths per minute), circulation (assessed via radial pulse or capillary refill), and mental status (ability to follow simple commands).

Manchester Triage System (MTS): As one of the most widely adopted triage systems in developed countries, MTS is known for its ease of use and rapid application. A key feature of MTS is its explicit specification of recommended waiting times for physician visits and patient care. It prioritizes patients based on presenting signs and symptoms, without requiring a hypothesis about the underlying diagnosis, utilizing 53 distinct flowcharts to guide the assessment. MTS employs five urgency groups: Red (requiring urgent physician visit), Orange (can wait 10 minutes), Yellow (can wait 1 hour), Green (can wait 2 hours), and Blue (can wait 4 hours). Notably, RETTS itself was developed from the Manchester Triage System.

Emergency Severity Index (ESI): Predominantly used in the United States, ESI differs from MTS by classifying patients based on both the acuity (severity) of their medical condition and the anticipated number of resources their care will require. ESI uses a 5-level scale (1-5), where levels 1 and 2 are determined by immediate acuity, while levels 3, 4, and 5 are determined by the projected resource needs. Resources include laboratory procedures, radiology, intravenous fluids, specific consultations, simple or complex procedures, and various forms of medication administration. Studies have indicated that ESI urgency levels are more effective in discriminating the need for hospitalization compared to MTS and the National Triage System (NTS).

A systematic review found no clear preference between ESI and MTS, as their overall performance appeared comparable. However, many of these studies were limited by single-center designs or specific patient populations, which restricted their generalizability. All three systems (ESI, MTS, and an informally structured system) generally demonstrated low sensitivity across all urgency levels but high specificity for the most critical levels (levels 1 and 2). The existence of multiple prominent triage systems and their varied approaches highlights that no single "perfect" triage system exists. Each system possesses strengths tailored to specific contexts or priorities, indicating that RETTS's design, with its combination of Vital Signs and Emergency Symptoms and Signs, represents a particular philosophical choice within this spectrum of triage methodologies.

5.2. The WEst coast System for Triage (WEST) as a Swedish Alternative

The WEst coast System for Triage (WEST) has emerged as a significant development in Swedish emergency care, specifically designed to address and mitigate the over-prioritization observed with the established RETTS© system.

Development Rationale and Principles: WEST was developed to achieve a more balanced triage that more accurately reflects the actual medical risk of patients. It is conceptually based on the South African Triage Scale (SATS) and, like RETTS, is a five-level, color-coded triage system. A distinguishing feature of WEST is its explicit integration of the emergency department staff's clinical judgment, often referred to as "clinical gestalt," and the patient's medical history. This makes clinical assessment an explicit variable in the triage process, alongside vital parameters (VPs) that are calculated using the updated National Early Warning Score (NEWS2).

Detailed Comparison of WEST's Prioritization Levels with RETTS: A pilot study comparing WEST and RETTS© found that WEST generally assigned lower levels of prioritization without any observed negative impact on patients' medical outcomes. Specifically, for patients initially triaged to the "orange" level in RETTS©, approximately 50% were subsequently down-prioritized to yellow or green levels when assessed with WEST. Similarly, for patients in the RETTS© "yellow" triage level, more than 55% were down-prioritized to the green triage level under WEST. The study confirmed that serious events within 72 hours were rare, and the few patients who died were consistently triaged to high-acuity levels in both systems.

Impact on Over-prioritization and Patient Outcomes: The study concluded that WEST has the potential to reduce over-prioritization, particularly within the orange and yellow triage levels of RETTS©, without an observed increase in medical risk. This reduction in over-prioritization could lead to more efficient allocation of emergency department resources, directing focus towards patients who are genuinely in urgent need of care and monitoring. The development and partial adoption of WEST directly addresses a known limitation of RETTS (over-prioritization). This demonstrates a dynamic and adaptive approach within the Swedish healthcare system, indicating a willingness to innovate and refine established practices based on observed challenges. The inclusion of "clinical gestalt" in WEST is a significant methodological difference, recognizing the value of experienced human judgment beyond strict algorithmic adherence.

Current Implementation Status and Challenges of WEST: WEST was initially rolled out at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Western Sweden between 2019 and 2021. Since then, it has been adopted by numerous other hospital EDs in the region, systematically replacing RETTS©. However, the implementation of WEST has not been without its challenges, with varying levels of enthusiasm observed among different emergency departments. One ED (ED1) displayed considerable enthusiasm and perceived WEST as a significant improvement in triage, while another (ED2) expressed reservations regarding both the implementation process and the new system itself. Despite these challenges, the majority of participating triage nurses (30 out of 36) concurred that WEST offered enhanced accuracy in identifying critically ill patients compared to RETTS©. The varying enthusiasm for WEST's implementation, despite its perceived accuracy, highlights the inherent challenges of organizational change and the influence of "subcultures within hospital organizations". This implies that even a demonstrably better system can encounter resistance, underscoring that technological or algorithmic superiority alone is insufficient for successful healthcare innovation; human factors and change management are equally critical.

Challenges and Limitations in RETTS Implementation and Operation

6.1. Operational and Systemic Implementation Hurdles

The implementation of new software systems, including those like RETTS, frequently encounters a range of common challenges that can impede a smooth transition and optimal functioning. These hurdles often include misaligned expectations between various stakeholders and vendors, difficulties in ensuring data integrity during the migration of information from existing systems, and a general lack of preparedness among both the project teams overseeing the implementation and the end-users who will operate the new system. Furthermore, insufficient support from the vendor after the initial rollout and the provision of inadequate training tools can significantly undermine successful adoption.

Resistance from employees who are accustomed to and comfortable with existing systems represents a substantial barrier to implementation. Overcoming this resistance necessitates clear communication regarding the benefits of the new software and comprehensive onboarding processes to familiarize staff with its functionalities. The successful integration of RETTS with existing healthcare IT infrastructure, such as Electronic Health Records (EHRs), is paramount for achieving streamlined workflows and efficient data transfers. While RETTS is specifically designed to connect with existing systems and integrate into patient journal systems , the actual process of achieving seamless integration can still present considerable challenges. Moreover, there is a recognized risk of declining productivity during the implementation phase, and failed implementations can incur significant costs, highlighting the importance of meticulous planning and execution. The challenges identified in general software implementation are directly applicable to RETTS, particularly given its software-based nature. This implies that while the clinical algorithm is central, the success of RETTS critically depends on effective IT project management, robust change management strategies, and continuous user support, extending beyond the mere medical efficacy of the system itself.

6.2. Gaps in Academic Research and Evaluation

Despite the widespread adoption and dominant position of METTS/RETTS in Swedish emergency departments, a significant limitation lies in the recognized "lack of high-quality studies regarding the validity and reliability" of the system. This absence of rigorous empirical evidence means that the full extent of its effectiveness and its long-term impact are not yet comprehensively understood.

A notable gap in current knowledge concerns the potential effect of METTS on patient waiting times, as there is a scarcity of published data directly addressing this crucial operational metric. Furthermore, there is a clear need for more extensive studies to investigate the economic aspects and cost-effectiveness of interventions related to triage systems. The significant gap in high-quality validity and reliability studies for a system as widely adopted as RETTS poses a substantial risk for evidence-based healthcare policy. It suggests that widespread adoption may have outpaced rigorous scientific validation, potentially leading to decisions based on perceived, rather than empirically proven, effectiveness. This creates a critical need for future research to solidify the system's empirical foundation.

6.3. The Persistent Issue of Over-prioritization

As previously discussed, RETTS has demonstrated a consistent tendency over time to prioritize patients to higher triage levels, particularly within the "orange" and "yellow" categories. This persistent and increasing trend of over-prioritization in RETTS suggests a potential "triage creep" phenomenon, where the threshold for assigning higher urgency levels gradually lowers over time. This could stem from a combination of factors, including a safety-first bias among clinicians, a lack of clear feedback mechanisms on over-triage rates, or a natural response to increasing pressures within the emergency department.

This over-prioritization presents considerable challenges in accurately identifying truly high-risk patients within the larger pool of "urgent" cases. The consequence is often increased waiting times for genuinely critical patients, and an exacerbation of emergency department crowding, which in turn negatively impacts the working environment for emergency staff. For instance, a study provided compelling evidence of this issue, showing that approximately 55% of patients triaged to the "orange" level in RETTS were ultimately discharged home, indicating a significant degree of over-triage at this level.

Future Directions and Recommendations for SweTRISS

7.1. Strategies for Continuous Improvement and Adaptation

The ongoing evolution of SweTRISS is crucial for maintaining its efficacy and relevance in a dynamic healthcare landscape. A foundational strength of RETTS is its commitment to continuous development, with regular updates based on the latest research and clinical guidelines to meet evolving healthcare needs. This commitment, coupled with Sweden's robust national data infrastructure and its proactive stance on innovation, as exemplified by the SIISH project aimed at accelerating the implementation of innovative solutions in healthcare , creates a fertile environment for integrating advanced technologies. This could transform RETTS from a rule-based decision support system into a more dynamic, predictive, and self-optimizing platform.

Potential Integration of AI and Digital Tools: Artificial intelligence (AI) and data interoperability tools offer significant potential to optimize clinician efforts, provide actionable insights, and enable more personalized treatments. Workflow simulation, including the creation of "digital twins" of hospital environments, can predict the impact of proposed operational changes, optimize patient flow, staff scheduling, and equipment utilization, and identify sustainable improvement opportunities without the need for costly real-world trials. Furthermore, digital check-in and triage kiosks show promise in accurately identifying high-acuity patients and streamlining operations by automating administrative tasks, thereby reducing the workload on clinical staff.

Synergy with National Care Intermediation Systems: The Swedish government's ongoing implementation of a new national care intermediation system, designed to identify excess capacity across the country and facilitate quicker access to care by leveraging accessible information on healthcare and waiting times , presents a strategic opportunity. Integrating RETTS data with this broader system could enable dynamic load balancing across hospitals, leading to a reduction in overall waiting times and improved resource utilization at a national scale, thereby addressing the persistent issue of long waiting times more comprehensively.

7.2. Addressing Over-prioritization and Enhancing Triage Accuracy

The persistent challenge of over-prioritization within RETTS necessitates targeted strategies for refinement and enhanced accuracy.

Lessons from the WEST System: The WEst coast System for Triage (WEST) has demonstrated success in reducing over-prioritization without compromising medical risk. This provides a clear blueprint for refining RETTS. A key feature of WEST that RETTS could potentially adopt is its explicit incorporation of clinical judgment, or "clinical gestalt". This acknowledges the value of experienced human intuition and assessment beyond strict algorithmic adherence, which can temper algorithmic rigidity.

Recommendations for Refining Triage Algorithms: This could involve a meticulous recalibration of the Emergency Symptoms and Signs (ESS) cards and Vital Signs (VS) thresholds, particularly for the "orange" and "yellow" triage levels. Such recalibration should be based on real-world outcome data to systematically reduce the proportion of over-triaged patients.

Enhanced Clinical Judgment Integration: Training programs for healthcare professionals could be enhanced to emphasize the nuanced application of RETTS, encouraging clinicians to integrate the system's output with their accumulated experience and clinical intuition. Implementing robust feedback mechanisms that provide individual clinicians with data on their over-triage rates could foster self-correction and continuous improvement in their triage practices. The existence of WEST and its demonstrated ability to reduce over-prioritization presents a direct, evidence-based solution to RETTS's primary identified flaw. This suggests that the future of SweTRISS might involve either a broader adoption of WEST or a strategic integration of WEST's core principles (especially clinical gestalt and recalibrated thresholds) into the next iteration of RETTS.

7.3. Strengthening Research and Robust Evaluation

Addressing the identified gaps in high-quality academic studies on RETTS's validity and reliability is paramount for the system's long-term credibility and effectiveness.

Call for Rigorous Studies: Future research must include multi-center, prospective, observational studies employing robust methodologies. These studies should comprehensively assess diagnostic accuracy, patient outcomes, resource utilization, and the system's direct impact on patient waiting times.

Standardized Data Collection: Leveraging Sweden's existing national quality registries for standardized data collection on triage performance, patient flow, and clinical outcomes across all emergency departments would enable more comprehensive and generalizable research findings.

Comparative Effectiveness Research: Direct head-to-head comparisons of RETTS with other prominent triage systems (e.g., WEST, MTS, ESI) in diverse patient populations within the Swedish context are essential to determine which system performs optimally under various clinical conditions.

Longitudinal Impact Studies: Research efforts should extend beyond short-term outcomes to assess the long-term impact of triage decisions on patient health, including readmission rates and overall healthcare costs. The current research gap creates a strategic vulnerability for SweTRISS. Without robust evidence, continuous improvements risk being based on anecdotal or incomplete data, potentially leading to suboptimal policy decisions and resource allocation. Prioritizing this research is not merely an academic exercise but a critical investment in the system's long-term effectiveness and credibility.

7.4. Enhancing Training and Professional Development Programs

Effective training and continuous professional development are indispensable for the successful implementation and evolution of SweTRISS.

Comprehensive and Continuous Training: While training is currently provided as part of the RETTS license , it should be continuously updated to reflect system changes, incorporate new research findings, and address lessons learned from issues such as over-prioritization.

Addressing Resistance to Change: Proactive strategies to address potential employee resistance to new systems or refinements must be integrated into training and implementation plans. This includes clearly articulating the rationale behind changes and demonstrating tangible benefits for both staff and patients.

Feedback Mechanisms: Implementing robust feedback loops for individual clinicians on their triage accuracy, particularly concerning over-triage, could foster self-correction and continuous improvement in clinical practice. Effective training and change management are not one-time events but continuous processes, especially for a system undergoing "continuous development". The observed resistance to WEST's implementation , despite its perceived accuracy, underscores that human factors are as critical as technical ones for successful system evolution.

Conclusion

The Swedish Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (SweTRISS), encompassing RETTS and its predecessor METTS, stands as a testament to Sweden's commitment to standardized, patient-centered emergency care. Its widespread adoption across nearly all Swedish Emergency Departments underscores its perceived value in streamlining patient assessment through a dual-factor approach of Vital Signs and Emergency Symptoms and Signs. This systematic methodology has demonstrably contributed to consistent decision-making and improved patient flow, particularly in identifying low-risk patients with high accuracy.

However, this comprehensive analysis reveals critical areas for strategic attention. The persistent challenge of over-prioritization, particularly at the "orange" and "yellow" triage levels, represents a significant operational inefficiency contributing to emergency department crowding and potentially increasing wait times for the most critically ill. The emergence and initial success of the WEST system in mitigating this over-triage provides a compelling blueprint for future refinements within SweTRISS, suggesting a need to integrate more nuanced clinical judgment alongside algorithmic assessments.

Furthermore, a notable gap in robust, high-quality academic studies on RETTS's long-term validity, reliability, and direct impact on patient waiting times presents a significant challenge to evidence-based policy-making. Leveraging Sweden's advanced national data infrastructure for rigorous, multi-center research is paramount to solidify the empirical foundation of SweTRISS and guide its future evolution.

Looking ahead, the strategic importance of SweTRISS will only grow. Its future success hinges on a proactive approach to continuous improvement, embracing technological advancements like AI and workflow simulation for predictive analytics and operational optimization. Critically, this must be coupled with a renewed focus on comprehensive, ongoing professional training and effective change management strategies to ensure consistent application and foster clinician buy-in. By addressing these challenges, SweTRISS can continue to evolve as a world-leading emergency triage system, ensuring efficient, equitable, and high-quality care for all patients within the Swedish healthcare landscape.

FAQ Section

1. What is the Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (RETTS)? RETTS is a Swedish triage system that combines vital signs with emergency symptoms and signs to provide a comprehensive assessment of a patient's condition in emergency departments.

2. Where was RETTS developed? RETTS was developed at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden.

3. What are the key components of the RETTS triage process? The RETTS triage process involves the assessment of vital parameters (VPs) and emergency signs and symptoms (ESS), followed by the assignment of triage priority levels based on these assessments.

4. How are patients prioritized in RETTS? Patients are prioritized based on the severity of their condition, as determined by the assessment of VPs and ESS. They are assigned one of five triage priority levels: Red (Immediate), Orange (Very urgent), Yellow (Urgent), Green (Standard), and Blue (Non-urgent).

5. What is RETTS-p? RETTS-p is the pediatric version of RETTS, designed to address the unique needs of pediatric patients. It includes specific criteria for assessing children's vital parameters and emergency signs and symptoms.

6. How effective is RETTS in pediatric emergency departments? Studies have shown that RETTS-p is a reliable triage system in pediatric emergency departments, with a high degree of inter- and intrarater reliability among nurses.

7. What are some challenges associated with RETTS? Challenges associated with RETTS include the potential for overtriage, increased waiting times for high-risk patients, and ambiguity in the assessment of vital signs criteria.

8. How does RETTS compare to other triage systems? RETTS is similar to other triage systems like ESI, CTAS, and MTS in that it assigns patients to triage levels based on the severity of their condition. However, RETTS uniquely combines vital parameter measurements with emergency signs and symptoms in the triage decision.

9. What educational interventions have been used to improve the reliability of RETTS application? Educational interventions involving paper-based scenarios have been used to improve the reliability of RETTS application, resulting in moderate agreement about the final levels of triage.

10. How has RETTS been adapted for international use? An English online version of RETTS has been developed, making the system internationally available and aligning it with more established triage systems.