Psychological Trauma Triage in Emergency Response

Explore psychological trauma triage in emergency settings, including recognizing shock and anxiety, addressing non-visible mental health injuries, and implementing holistic approaches to patient care that integrate psychological first aid into traditional triage systems.

In the dynamic and often chaotic environment of emergency response, the immediate assessment and management of physical injuries are paramount. However, a parallel and equally critical domain exists: the triage of psychological trauma. This report delineates the foundational concepts, established methodologies, emerging tools, ethical considerations, and observed outcomes pertinent to psychological trauma triage, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding for professionals engaged in disaster and emergency management.

Defining Psychological Trauma and its Impact in Emergency Settings

Psychological trauma is understood as any profoundly disturbing experience that precipitates significant fear, helplessness, dissociation, confusion, or other disruptive emotional states intense enough to exert a lasting negative influence on an individual's attitudes, behavior, and overall functioning. Such events can originate from human actions, including acts of terrorism or industrial accidents, or from natural phenomena like earthquakes. A common characteristic of these traumatic experiences is their capacity to fundamentally challenge an individual's perception of the world as a just, safe, and predictable environment.

In the immediate aftermath of emergencies, individuals frequently exhibit a spectrum of acute stress reactions. These may manifest as disorientation, confusion, frantic or panicky states, extreme withdrawal or apathy, severe irritability or anger, and excessive worry. While these responses can appear extreme and cause considerable distress, they are often considered normal reactions to an abnormal situation. The common psychological and physiological manifestations of trauma include feelings of numbness, being stunned or overwhelmed, denial, sadness, grief, depression, irritability, mood swings, self-blame or blaming others, helplessness, and a pervasive fear of the event recurring. Cognitive impacts may involve problems with concentration or memory, while physical symptoms can range from headaches and chest pain to nausea, stomach pain, diarrhea, and sleep disturbances. Behavioral changes, such as hyperactivity, hypervigilance, and an increase in alcohol or drug consumption, are also frequently observed.

The characterization of severe distress as a "normal response to an abnormal situation" presents a nuanced challenge in acute trauma response. While this framing is crucial for validating a survivor's experience and preventing the pathologization of immediate reactions , it carries the inherent risk that severe psychological distress might be inadvertently overlooked or deprioritized for intervention. This situation necessitates a delicate balance: providing compassionate support that acknowledges the universality of such reactions, while simultaneously employing clear criteria to identify individuals whose distress patterns or risk factors indicate a higher likelihood of developing chronic problems, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The approach of early psychological first aid, which is supportive and non-pathologizing, becomes particularly pertinent in this context, guiding initial interactions to both normalize reactions and discern the need for further attention.

The Role and Objectives of Psychological Triage

Triage, a term derived from the French word "trier," meaning to sort or organize, fundamentally involves categorizing patients based on the severity of their injuries or conditions to prioritize care. Within the domain of psychological trauma, this process is adapted to assess survivors' immediate concerns and needs, enabling the flexible implementation of supportive activities.

The overarching objectives of psychological trauma triage are multifaceted. They encompass establishing a sense of safety and security for affected individuals, facilitating their connection to restorative resources, actively working to reduce acute stress-related reactions, fostering adaptive coping mechanisms, and ultimately enhancing natural resilience. A key aim is to rapidly identify individuals who are experiencing acute stress reactions and appear to be at risk for significant impairment in functioning. Concurrently, it also seeks to support those who may be at lower immediate risk, with the goal of building their inherent capacity for coping and resilience.

Traditional physical trauma triage primarily focuses on maximizing immediate survival and the efficient allocation of scarce resources in life-threatening scenarios. In contrast, psychological triage, while operating within emergency settings, extends its mandate beyond immediate stabilization. It embraces a broader, more nuanced objective that includes fostering adaptive functioning, promoting effective coping strategies, and building long-term resilience. This expanded scope implies a shift from the "golden hour" for physical interventions to a "golden month" for effective psychological care, acknowledging a more protracted window for impactful support. This dual mandate—addressing acute psychological needs while simultaneously building foundations for sustained well-being—underscores that psychological well-being is not a secondary concern but an integral component of overall recovery, demanding its integration from the earliest phases of emergency response.

Distinction from Physical Trauma Triage and Traditional Mental Health Services

While a team-based approach is inherently utilized in the treatment of trauma patients , the methodologies and priorities of physical trauma triage diverge significantly from those of psychological trauma triage. Traditional physical trauma triage, exemplified by systems such as START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment) and SALT (Sort, Assess, Lifesaving Interventions, Treatment/Transport), is primarily concerned with objective physiological criteria—namely, airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure—and identifiable anatomical injuries. This process typically involves a sequential assessment and immediate intervention aimed at addressing life-threatening physical conditions. The objective is to rapidly determine medical priority and the most appropriate transport destination for the injured patient.

Conversely, psychological triage applies the principles of sorting to individuals presenting with psychological distress. Its focus is on observable behavioral disturbances, the presence and degree of risk to self or others, and the overall level of distress experienced by the individual. Unlike physical triage, which prioritizes the most critically injured for immediate life-saving medical interventions , psychological triage also accounts for the potential for long-term psychological sequelae, with an aim to prevent the development of chronic mental health problems.

Furthermore, it is crucial to differentiate psychological trauma triage, particularly through the lens of Psychological First Aid (PFA), from traditional, formal mental health services. PFA is explicitly not professional counseling or psychological debriefing; it does not involve pressuring individuals to articulate or analyze their feelings about the traumatic event. Instead, PFA functions as an initial psychosocial support approach, serving as a distinct and early intervention that precedes, rather than replaces, formal mental health treatment services.

The historical emphasis in emergency response has predominantly been on physical injuries. However, a discernible evolution is evident in contemporary emergency frameworks, where mental health considerations are increasingly being integrated from the outset. This progression indicates a transition from a siloed approach, where physical and mental health responses were treated as separate entities, to a more holistic, interprofessional model of trauma care. This growing integration necessitates enhanced cross-training and the development of collaborative protocols that bridge the traditional divides between physical and mental health disciplines. The underlying implication is that future emergency response paradigms will increasingly recognize the interconnectedness of physical and psychological well-being, demanding simultaneous assessment and intervention strategies from the earliest moments of a crisis to ensure comprehensive patient care and recovery.

Foundational Principles and Models of Psychological First Aid (PFA)

Psychological First Aid (PFA) stands as a cornerstone of psychological trauma triage, offering an immediate, humane, and supportive response in the aftermath of critical incidents. This section outlines its core principles, practical application, and various established models.

Core Actions and Guiding Principles of PFA

Psychological First Aid is recognized as an evidence-informed, modular approach designed to assist individuals across all age groups in the immediate aftermath of disasters and acts of terrorism. Its fundamental purpose is to mitigate initial distress and to foster both short-term adaptive functioning and long-term coping mechanisms.

The principal actions guiding PFA are oriented towards promoting recovery and resilience. These include establishing a sense of safety and security for affected individuals, facilitating their connection to restorative resources, actively working to reduce stress-related reactions, nurturing adaptive coping strategies, and enhancing inherent natural resilience. PFA endeavors to create an environment that is conducive to an individual's long-term recovery by instilling feelings of safety, fostering social connections, and empowering them to participate actively in their own healing process.

The core components of PFA, as outlined in various guidelines, involve a structured yet flexible approach:

Contact and Engagement: This action focuses on responding to or initiating contact with affected individuals in a non-intrusive, compassionate, and helpful manner.

Safety and Comfort: The goal here is to enhance immediate and ongoing physical and emotional safety, attend to acute losses, and provide comfort, especially for vulnerable populations like unaccompanied children.

Stabilization: When individuals are emotionally overwhelmed or disoriented, simple interventions are employed to calm and reorient them, managing intense stress reactions. This may involve establishing rapport, validating experiences, offering empathy, providing privacy, and, if appropriate, recruiting support from family or friends.

Information Gathering on Current Needs and Concerns: This involves helping individuals articulate their immediate needs and concerns, gathering additional information as appropriate, and tailoring PFA interventions based on knowledge of post-disaster risk factors.

Practical Assistance: Providing practical help to survivors in addressing their immediate needs and concerns, often by breaking down problems into manageable steps.

Connection with Social Supports: Assisting individuals in establishing or re-establishing contact with their primary support persons, such as family members, friends, and community resources, to leverage social networks for recovery.

Information on Coping: Offering basic psychoeducation about common stress reactions to normalize feelings and helping individuals identify and enhance positive coping strategies.

Linkage with Collaborative Services: Connecting survivors with additional services they may need immediately or in the future, including mental health services, public-sector services, and other community organizations.

A significant characteristic of PFA is its design for delivery by "anyone with a minimum of training," extending its reach beyond licensed mental health professionals to include first responders, volunteers, and other disaster response workers. This broad applicability signifies a deliberate strategy to democratize immediate psychological support in emergency contexts. The implication is that PFA is intended to be a universal skill set, fundamentally integrating psychological support into the initial phases of emergency response. This decentralization of immediate mental health care can substantially broaden the reach of support, alleviate the burden on specialized professionals during the overwhelming aftermath of a crisis, and thereby serve as a critical component in building community resilience.

Practical Application of PFA in Disaster Scenarios

The practical application of Psychological First Aid is versatile, adapting to various settings encountered during disaster response. PFA is effectively deployed in general population shelters, medical triage areas, emergency departments, staging areas and respite centers for first responders, crisis hotlines, and family assistance centers.

A widely recognized and straightforward model for delivering PFA, particularly highlighted in the FEMA-published Listen, Protect and Connect handbook, involves three fundamental steps: Listen, Protect, and Connect.

Listen: This initial step requires genuine interest and openness to hear an individual's concerns. It involves active, non-judgmental listening, paying close attention to both verbal and non-verbal cues. Often, observed actions and behaviors may be the primary indicators of a person's coping status after a disaster. Key actions include:

Making the first move: Initiating contact with a simple, compassionate inquiry like "how are you doing?" can signal willingness to listen, as many survivors may not approach for help.

Accepting silence: Understanding that simply being present for someone, even if they are unwilling to talk, is a valuable form of support.

Validating feelings: Acknowledging that there are "no right or wrong feelings" and avoiding the imposition of one's own worldview is crucial, as everyone reacts uniquely to trauma.

Sharing common reactions: Informing individuals about typical stress reactions post-disaster can help normalize their experiences and reduce feelings of isolation.

Affirming coping strategies: Recognizing and encouraging existing coping mechanisms that have proven effective for the individual in the current or past stressful situations.

Throughout this listening process, the practitioner aims to identify the most pressing practical concerns where immediate assistance can be provided, while also noting any persistent or severe reactions that may necessitate professional mental healthcare.

Protect: This step focuses on shielding individuals from ongoing stressors and addressing their immediate practical and psychological needs. It involves:

Addressing basic needs: Providing essential resources such as food, water, and warm blankets, as well as assisting with transportation or childcare. This also includes connecting individuals with recovery centers or aid organizations like FEMA or the Red Cross.

Providing physical first aid: Attending to any immediate physical injuries.

Expressing sympathy and support: Maintaining a consistent, empathetic presence, even when the underlying problem cannot be fully resolved.

Providing accurate information: Answering questions honestly with factual information about the event and available services, and acknowledging when information is unknown, given the rapidly evolving nature of disaster information.

Encouraging positive coping: Supporting and building upon individuals' constructive coping strategies while discouraging destructive behaviors such as substance abuse.

Reducing further disaster exposure: Advising survivors to limit exposure to repetitive or graphic media coverage, including social media, which can exacerbate psychological trauma.

Promoting healthy behaviors: Encouraging adequate rest, nutrition, hydration, and physical activity, as well as engagement in non-disaster related activities.

Developing a safety plan: Assisting individuals in creating plans to mitigate worries about potential future disasters.

Connect: The final step aims to foster a sense of community and social connectedness, which is highly beneficial for psychological well-being post-disaster. This includes:

Facilitating social interaction: Encouraging individuals to spend extra time with family and friends, fostering new friendships, and maintaining existing relationships.

Linking to resources: Assisting in locating family members, sharing basic resources, and providing access to helpful local community resources.

The concept of a "golden month" for psychological care, contrasting with the "golden hour" for physical trauma , highlights a crucial aspect of psychological intervention. This extended timeframe suggests that the window for effective psychological support is considerably longer than for immediate physical injuries, enabling more sustained, early-phase interventions. This implies that early interventions like PFA are not merely singular events but rather integral components of a continuous effort spanning several weeks. Consequently, emergency response planning must account for the prolonged presence of support personnel and resources in affected communities, ensuring that psychological care extends well beyond the immediate acute phase of a disaster.

Key PFA Models and Frameworks (e.g., Listen, Protect, Connect; SAMHSA Inventory)

Several PFA models and frameworks have been developed to guide immediate psychological support in emergency contexts. The "Listen, Protect, Connect" model, conceptualized by Dr. Merritt Schreiber, is a practical and widely adopted approach for delivering PFA.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Disaster Behavioral Health Interventions Inventory provides a comprehensive overview of various acute/immediate response interventions, including different PFA models. These interventions are designed to mitigate the development of serious mental disorders and support natural recovery processes following traumatic events. Specific PFA models and related frameworks detailed in this inventory include:

The PFA RAPID Model: Developed by Johns Hopkins Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Center, this model utilizes an acronym (Reflective Listening, Assessment, Prioritization, Intervention, and Disposition) to guide public health professionals in providing PFA concepts and skills.

Nebraska PFA: This program trains disaster response professionals to provide psychological support to survivors through a segmented modular training approach.

PFA for Schools: A manualized approach specifically tailored for assisting children, adolescents, adults, and families in the aftermath of school crises, disasters, or terrorism events.

Building Workforce Resilience Through the Practice of Psychological First Aid—A Course for Supervisors and Leaders (PFA-L): This course focuses on teaching PFA principles and their application to leaders and supervisors, covering stress reactions and core components of PFA from a managerial perspective.

PFA is also adapted for various specific audiences, including religious leaders and individuals experiencing homelessness, demonstrating its flexibility and broad applicability across diverse populations and settings.

The consistent description of PFA as an "initial early intervention" and a "first step in supporting individuals" positions it as the foundational layer within a broader stepped-care model. It is explicitly acknowledged that PFA may not be sufficient for all individuals, and those exhibiting more severe or protracted reactions may necessitate "more intensive interventions". This understanding implies that PFA is not a definitive, standalone solution but rather a crucial entry point into a continuum of care. Consequently, effective psychological trauma triage must incorporate clear pathways for escalating care to more formal mental health services, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD, for individuals whose distress persists or intensifies beyond the acute phase. This approach ensures continuity of care and is vital for preventing the development of chronic psychological issues.

Advanced Psychological Triage Systems and Tools

Beyond the foundational principles of Psychological First Aid, specialized systems and tools have been developed to enhance the systematic assessment and management of mental health needs in emergency response. These advanced approaches facilitate more precise identification of at-risk individuals and optimize resource allocation.

PsySTART: A Rapid Mental Health Triage and Incident Management System

PsySTART, an acronym for Psychological Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment, represents an evidence-based, rapid mental health triage strategy and comprehensive system. Its primary application is during emergencies to swiftly assess individuals' exposure to toxic stressors and traumatic events.

A key feature of PsySTART is its integration of information technology, specifically Geographic Information Systems (GIS), to generate real-time data concerning affected locations and the severity of trauma experienced by individuals within those areas. This technological integration allows for dynamic situational awareness at both individual and population levels.

The core objectives of PsySTART include identifying individuals who are experiencing an acute mental health crisis or emergency, those who would benefit from a secondary mental health assessment, and individuals at heightened risk for developing chronic mental health disorders. Furthermore, PsySTART contributes to determining the "trauma temperature" of a community, providing a population-level understanding of the psychological impact of an event.

The risk factors assessed by the PsySTART tool are comprehensive, encompassing a range of direct and indirect exposures and vulnerabilities. These include: extreme panic or fear, felt life threat, witnessing injury or death, the death of family members or pets, disaster-related physical injury, being trapped or experiencing delayed evacuation, having missing family members, unaccompanied children, an uninhabitable home, family separation during the event, a pre-existing mental health history, a history of prior trauma, and presenting a danger to self or others.

The versatility of PsySTART is notable, as it can be effectively utilized by a broad spectrum of personnel, including medical professionals, mental health professionals, first responders, and trained non-professional volunteers. The system is available in both mobile-optimized web-based applications and companion paper versions, ensuring usability even in environments with unreliable internet access.

The explicit use of GIS and real-time data collection on traumatic exposures within PsySTART to guide decisions on "where and what types of mental health resources should be directed" marks a significant advancement in psychological trauma triage. This approach shifts from a purely individual assessment to a population-level understanding of mental health needs, thereby enabling the more ethical and rational allocation of mental health resources, particularly in pediatric contexts. This integration of data analytics for strategic resource deployment is crucial. By precisely identifying areas with high concentrations of affected individuals and specific needs, PsySTART facilitates a more efficient and equitable distribution of often limited mental health resources. This directly addresses the challenge of a "mental health surge" that typically follows large-scale emergencies, optimizing the response by aligning resources with demonstrated need.

The Anticipate, Plan, Deter (APD) Responder Resilience Program

The Anticipate, Plan, Deter (APD) model represents a proactive and specialized approach to supporting the mental health of emergency personnel and first responders. These individuals frequently operate under extreme duress, often prioritizing the needs of others over their own well-being during crises.

The APD program provides a structured framework for developing comprehensive mental health surveillance and support systems specifically tailored for emergency personnel. Its core tenets are encapsulated by its name:

Anticipate: This involves understanding the various stressors and psychological impacts that responders may encounter, including traumatic and cumulative stressors.

Plan: This component focuses on the pre-deployment development of individualized resilience plans, which equip responders with strategies to manage stress and maintain well-being before they are exposed to traumatic events.

Deter: This emphasizes continuous self-monitoring for emotional and psychological stability throughout a response, enabling responders to identify when to activate their personal coping plans.

A critical element of the APD model is its integration of the PsySTART-R (Responder Self-Triage System). This tool functions as a "personal stress dosimeter," allowing individual responders to confidentially monitor their cumulative exposure to traumatic stress risk factors on a daily basis. As risk exposure increases, the PsySTART-R provides feedback that encourages the individual to utilize their pre-developed personal resilience plan and seek professional mental health support if needed. This system also allows incident commanders to monitor population-level risk within a responder group, informing broader support strategies.

The design of APD, with its explicit focus on pre-incident and ongoing support for first responders , distinguishes it from victim-centric triage models. Its emphasis on "hazard specific stress inoculation" and the creation of individualized resilience plans

before deployment represents a fundamental shift towards a proactive, preventative approach to psychological trauma. This is a crucial recognition that first responders, despite their training, are not immune to the psychological impacts of their work. Implementing proactive resilience programs like APD is therefore essential for preserving the mental well-being and operational effectiveness of emergency personnel. Such programs contribute significantly to reducing the long-term consequences of cumulative stress and moral injury, thereby ensuring the sustained capacity and resilience of emergency response capabilities.

National and International Mental Health Triage Scales

Standardized mental health triage scales play a vital role in categorizing the urgency of psychological distress and guiding appropriate responses in emergency settings. Two prominent examples include the Australian Mental Health Triage Tool and the UK Mental Health Triage Scale.

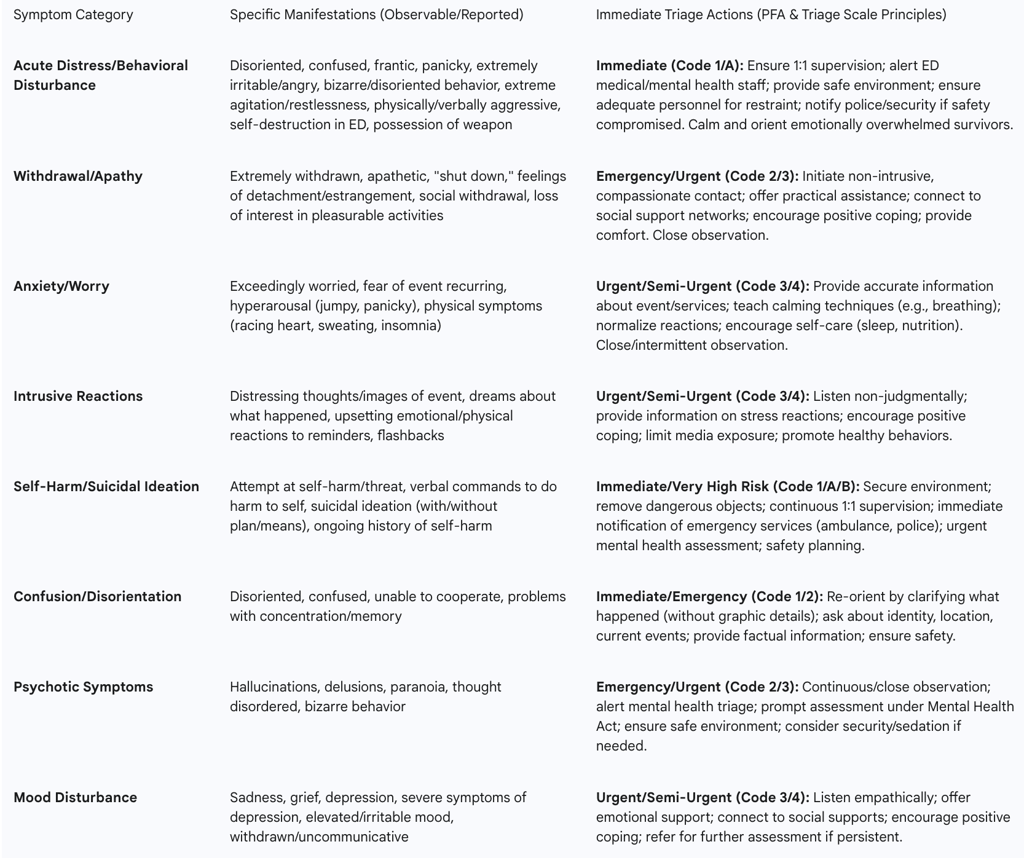

Australian Mental Health Triage Tool (AMHTT): This tool employs a five-level triage code system, ranging from "Immediate" (Code 1) to "Non-urgent" (Code 5), to assess and manage patients based on the severity of their behavioral disturbance and the level of risk to themselves or others.

Code 1 (Immediate): This code is assigned when there is a definite danger to life, either to the patient or others. Typical presentations include severe behavioral disorder with an immediate threat of dangerous violence, observed violent behavior, possession of a weapon, self-destructive actions in the Emergency Department (ED), extreme agitation, disorientation, or reported command hallucinations to harm self or others. Management mandates continuous 1:1 visual surveillance, immediate alerts to ED medical and mental health staff, and ensuring adequate personnel for restraint.

Code 2 (Emergency, within 10 minutes): Indicates a probable risk of danger to self or others, or if the patient is physically restrained or exhibits severe behavioral disturbance. Observed behaviors include extreme agitation, physical/verbal aggression, confusion, hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, or high risk of absconding. Actions require continuous visual surveillance, immediate alerts, provision of a safe environment, adequate restraint personnel, and prompt assessment under relevant mental health acts.

Code 3 (Urgent, within 30 minutes): Signifies a possible danger to self or others, moderate behavioral disturbance, or severe distress. Presentations may include suicidal ideation without a clear plan, acute psychosis, or severe mood disturbance. Close observation (maximum 10-minute intervals) is required, with alerts to mental health triage and monitoring for escalating distress.

Code 4 (Semi-urgent, within 60 minutes): Applied for moderate distress with no immediate risk to self or others. Patients may present with pre-existing mental health disorders or symptoms of anxiety/depression without suicidal ideation. Intermittent observation (maximum 1-hour intervals) and discussion with the mental health triage nurse are recommended.

Code 5 (Non-urgent, within 120 minutes): For situations where there is no danger to self or others and no acute distress or behavioral disturbance. This includes known patients with chronic symptoms, social crises, or requests for medication. General observation and referral to the treating team are appropriate.

UK Mental Health Triage Scale: This scale categorizes the urgency of mental health needs using a system of triage codes (A-G), each corresponding to specific response types and recommended actions for mental health and other emergency services.

Code A (Emergency, Immediate Referral): This is for current actions endangering self or others, such as overdose, suicide attempt, violent aggression, or possession of a weapon. The triage clinician must immediately notify ambulance, police, and/or fire services, and provide telephone support.

Code B (Very High Risk, within 4 hours): Indicates a very high risk of imminent harm to self or others, with a clear plan or means, ongoing history of self-harm or aggression, or very high-risk behavior associated with perceptual or thought disturbance. This requires urgent assessment under the Mental Health Act, crisis team/liaison assessment, or advice to attend an Accident & Emergency (A&E) department.

The structured, multi-level criteria provided by both the Australian and UK mental health triage scales reflect a broader movement towards standardization in psychological emergency response. However, it is also acknowledged that these tools can be "adapted to local contexts" and that "management principles may differ according to individual health service protocols and facilities". This observation highlights a critical tension between the pursuit of universal consistency and the necessity for contextual flexibility. While standardization is vital for ensuring consistent care quality and facilitating inter-agency collaboration, the allowance for local adaptation recognizes the diverse operational realities, cultural nuances, and resource availability across different regions and organizations. Effective psychological triage frameworks must therefore achieve a judicious balance, integrating universal principles with the capacity for local modification to ensure practical applicability and optimize patient outcomes across varied emergency scenarios.

Brief Screening and Observational Assessment Tools

In high-stress emergency environments, the ability to rapidly assess psychological status is crucial. This necessitates the use of brief screening tools and observational assessment methods.

Brief Trauma Questionnaire (BTQ): This is a 10-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess traumatic exposure based on DSM-5 Criterion A.1 (life threat or serious injury). It serves to identify whether an individual has experienced a Criterion A event or to categorize the types of such events they have encountered.

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): A 20-item self-report measure, the PCL-5 assesses the 20 DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD. Its utility extends to monitoring symptom changes during and after treatment, screening individuals for PTSD, and providing a provisional PTSD diagnosis. Completion typically takes 5-10 minutes.

Acute Stress Disorder Structured Interview (ASDI-5) and Acute Stress Disorder Scale (ASDS): These tools are utilized for the assessment of Acute Stress Disorder (ASD), a diagnosis that can be considered between 3 days and one month following a traumatic event. ASD is recognized as a risk factor for the subsequent development of PTSD.

ABCDE-Psy Scale: This is a hetero-administered measure developed for the primary psychological assessment of acute stress response to potentially traumatic events. It is designed to aid emergency professionals in recognizing behavioral symptoms through subjective observation, identifying potential risks in a person's psychological state, and guiding immediate actions, including activating specialized psychological services.

Rapid Triage Assessment (General): In the context of emergency nursing, a rapid triage assessment involves a quick (60-90 seconds) "across-the-room" survey to identify patients requiring immediate care from those who can safely wait. This observational assessment includes evaluating a patient's general appearance, body language (e.g., pain, fear, anxiety, agitation), skin tone, gait, and level of consciousness (using scales like Glasgow Coma Scale or AVPU - Alert, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive).

The reliance on self-report or structured interviews for many psychological screening tools, such as the BTQ, PCL-5, and ASDS , contrasts with the imperative for rapid, observational assessment often required in initial emergency triage. The ABCDE-Psy scale is notable as a "non-diagnostic measure" for evaluating initial psychological response, acknowledging that immediate reactions are typically adaptive and not indicative of psychopathology due to temporal criteria. This situation underscores a fundamental tension between the need for swift assessment in high-stress environments and the inherent complexity of psychological diagnosis. Triage tools in these settings must be concise and actionable, prioritizing the identification of immediate risk and acute distress over definitive clinical diagnoses. This implies a strategic, tiered assessment framework where initial rapid screening serves to identify individuals who warrant subsequent, more comprehensive evaluation by qualified mental health professionals. Such an approach ensures that immediate psychological needs are addressed without inadvertently over-pathologizing normal acute stress reactions.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Psychological Triage Models

Target Populations and Tailored Interventions

Effective psychological trauma triage necessitates a nuanced understanding of the diverse populations affected by emergencies, as their needs and vulnerabilities vary significantly. Interventions must be tailored to address the unique psychological impacts experienced by direct victims, first responders, witnesses, and other vulnerable groups.

Psychological Needs of Direct Victims and Survivors

Direct victims and survivors of traumatic events experience a profound and immediate psychological impact. They may be disoriented, confused, frantic, panicky, extremely withdrawn, apathetic, "shut down," or exceedingly worried. Common reactions include feelings of numbness, denial, sadness, grief, depression, irritability, anger, self-blame, helplessness, and a persistent fear of the event recurring. Physical manifestations such as headaches, chest pain, nausea, stomach pain, diarrhea, hyperactivity, hypervigilance, increased substance use, and sleep disturbances are also frequently observed.

The initial psychological reactions, while intense, are often considered normal responses to an abnormal situation, and most individuals are expected to recover within 6 to 16 months. However, a significant proportion may develop more enduring difficulties, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Prevalence estimates for PTSD can range from 30% to 40% among direct victims, with complications like complicated bereavement also increasing the risk for depression and substance abuse.

Interventions for this population in the immediate aftermath focus on Psychological First Aid (PFA), which aims to reduce initial distress, foster adaptive functioning, and link individuals to further services if needed. PFA emphasizes establishing safety and comfort, providing practical assistance, connecting individuals to social support networks, and offering information on coping strategies. For those with persistent or severe reactions beyond the acute phase, more intensive interventions such as Prolonged Exposure (PE), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) are recommended.

Mental Health Support for First Responders and Emergency Personnel

First responders, including police officers, firefighters, and emergency medical service personnel, are frequently the first individuals on the scene of a crisis. This occupational exposure places them at significant risk for experiencing stress and traumatic events, which can accumulate over time and contribute to diminished mental health and wellness. Studies indicate that responders to terrorist attacks or mass casualty incidents can experience high rates of PTSD, with one study reporting a 20% prevalence of mental health treatment needs among rescue personnel at the Oklahoma City bombing. They may also develop unhealthy substance use behaviors as coping mechanisms for job-related stress.

The psychological vulnerability of first responders, who are trained to manage physical crises, is a critical aspect that demands specialized attention. Their repeated exposure to traumatic events and the inherent moral dilemmas they may face in resource-scarce environments contribute significantly to their susceptibility to psychological trauma and moral injury. This situation necessitates the implementation of dedicated, proactive mental health support programs. The Anticipate, Plan, Deter (APD) Responder Resilience Program, for instance, is designed to provide pre-incident and ongoing support for these professionals, focusing on "hazard specific stress inoculation" and individualized resilience plans

before deployment. Such proactive measures are essential for maintaining the mental well-being and operational effectiveness of emergency personnel, mitigating the long-term impact of cumulative stress and moral injury, and ultimately ensuring the sustainability of emergency response capabilities.

Federal efforts in the United States have recognized these unique risks, with programs aimed at improving first responder mental health, some specifically targeting post-disaster response. In the UK, organizations like Mind, St John Ambulance, and the College of Paramedics offer mental health support and training, including Mental Health First Aid, peer support programs, and suicide prevention training, addressing the unique stressors faced by emergency services personnel.

Addressing the Needs of Witnesses, Families, and Vulnerable Groups

Beyond direct victims and responders, other populations are significantly impacted by traumatic events. Witnesses to grotesque sights or those voluntarily joining rescue efforts, even untrained "good samaritans," are at risk for high rates of PTSD and associated problems like depression and substance abuse. Families of victims, particularly those who have lost loved ones, may experience complicated bereavement, increasing their risk for mental health issues.

Children are of particular concern in the aftermath of disasters, requiring reassurance, safety, and opportunities to discuss their experiences. Vulnerable groups, including the elderly, individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions, those with a history of trauma, and those lacking strong social support networks, are at higher risk for severe and prolonged psychological effects. Cultural and religious variations also influence how traumatic stress is expressed and perceived, necessitating culturally sensitive interventions.

Tailored interventions for these groups involve:

Psychoeducation: Providing information about common stress reactions to normalize experiences and reduce stigma.

Social Support: Connecting individuals to family, friends, and community resources to foster a sense of connection and reduce isolation.

Practical Assistance: Addressing basic needs like food, water, shelter, and transportation, which can significantly reduce psychological distress.

Specialized Programs: For children, PFA models adapted for schools are available. For those with pre-existing conditions or severe reactions, early identification and referral to professional mental health services are crucial.

5. Ethical Considerations and Challenges in High-Stress Environments

The application of psychological trauma triage in emergency settings, particularly during mass casualty incidents, introduces a complex array of ethical considerations that challenge conventional medical principles and can profoundly impact healthcare providers.

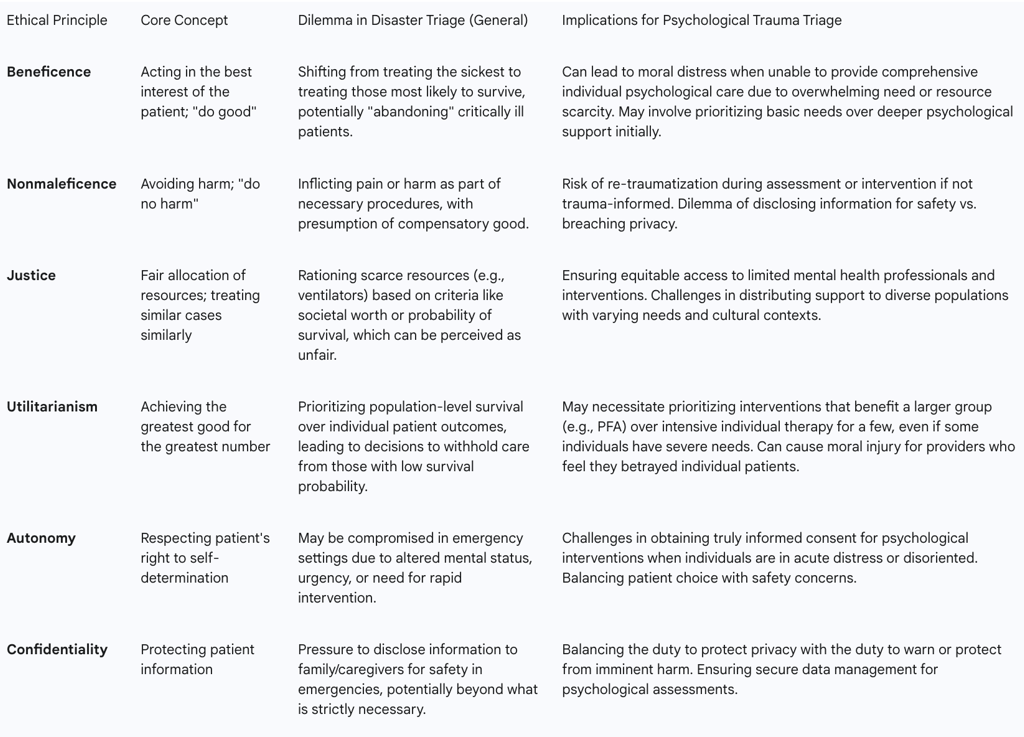

The Utilitarian Dilemma in Mass Casualty Triage

In routine medical practice, the prevailing ethical principles guiding care are typically autonomy, beneficence (acting in the patient's best interest), nonmaleficence (doing no harm), and justice (fair distribution of care). This typically translates to prioritizing the care of the most critically ill patients. However, during catastrophic situations or mass casualty incidents (MCIs), a fundamental shift in ethical approach occurs: the system transitions to a utilitarian ethical theory.

Utilitarianism in disaster triage prioritizes achieving "the greatest good for the greatest number of people" through the most efficient use of scarce resources. This means that decisions are made to optimize overall patient outcomes, even if it necessitates deferring treatment for those with minor injuries or, more controversially, for those with severe injuries who are unlikely to survive despite extensive resources. For instance, patients in cardiopulmonary arrest may not receive CPR, and critically ill patients with minimal chance of survival might be "black-tagged," receiving only comfort measures, even if it hastens death. This approach directly conflicts with the daily ethical principles that healthcare professionals, such as emergency room triage nurses, are trained to uphold, leading to significant moral distress.

The conflict between traditional medical ethics (beneficence for the individual patient) and disaster ethics (utilitarianism for the greatest good) creates profound moral distress and can lead to moral injury for healthcare professionals. This is a critical, often overlooked, aspect of emergency response. Clinicians are forced to make decisions that contradict their deeply held professional and personal values, such as abandoning patients who appear likely to die to allocate resources to those with a higher probability of survival. The lack of clear standards and implementation guidelines for such decisions exacerbates this moral burden. Transparency in the development of triage rules, with public and professional input, is essential to build confidence in the fairness of these difficult decisions.

Moral Distress and Moral Injury Among Healthcare Providers and Responders

The ethical dilemmas inherent in disaster triage contribute significantly to moral distress and, in severe cases, moral injury among healthcare providers and first responders. Moral distress arises when individuals know the ethically correct action but are constrained from performing it due to institutional or situational limitations. Moral injury, a deeper and more pervasive psychological impact, occurs when a person's actions, or inactions, during a traumatic event violate their deeply held moral compass and ethical expectations for themselves.

Sources of moral injury in healthcare workers during disasters include:

Being forced to make decisions that affect the survival of others, or where all options lead to a negative outcome.

Engaging in actions contrary to personal beliefs (acts of commission) or failing to act in line with beliefs (acts of omission).

Witnessing significantly more suffering and death than typically expected.

Lacking necessary tools or training to save a patient.

Providing care while facing personal life threat.

Feeling compelled to choose between patient care and family safety during pandemics.

Witnessing perceived unjustifiable acts or policies without the power to intervene.

The consequences of moral injury can be severe, including pervasive feelings of guilt ("I did something bad") and shame ("I am bad"), self-doubt, self-loathing, social isolation, withdrawal, increased irritability, aggression, misconduct, and changes in ethical or religious beliefs. These feelings can erode trust in oneself and others, leading to hopelessness, helplessness, anger, and betrayal, ultimately contributing to depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems.

Addressing moral injury requires significant processing, often involving professional psychological help, but also proactive "boots on the ground" efforts like peer support and open dialogue. Leaders have a crucial role in preventing moral injury by increasing communication, normalizing stress reactions, expressing gratitude, and providing support and referral sources.

Navigating Confidentiality, Informed Consent, and Re-traumatization

Ethical practice in psychological trauma triage also involves navigating complex issues of confidentiality, informed consent, and the risk of re-traumatization, especially in high-stress, rapidly evolving emergency environments.

Confidentiality: Maintaining patient confidentiality is a cornerstone of ethical practice. However, in emergency settings, there can be pressure to disclose more information than necessary to family members or caregivers, particularly when patient safety is at stake. The ethical approach is to disclose only the necessary information to ensure safety without breaching privacy. For example, if a child is suicidal, parents can be informed of the child's intentions without revealing other details. Emergency helplines and crisis support services emphasize confidentiality, while also noting limits when there is immediate danger.

Informed Consent: Obtaining informed consent for psychological interventions can be challenging in chaotic disaster environments, especially when individuals are disoriented or in acute distress. While verbal consent is recommended for therapy sessions to provide assurance and signal readiness to proceed, asking permission before sensitive questions is also suggested to avoid re-triggering trauma. In research contexts involving trauma-affected populations, voluntary and informed consent is paramount, considering potential language/cultural barriers or dependent relationships.

Re-traumatization: A significant ethical concern is the risk of re-traumatization during assessment or intervention. Research encounters, even seemingly innocuous elements like music or scent, can trigger past trauma. Compromising trust, choice, collaboration, empowerment, and safety can lead to trauma-related distress or re-traumatization, potentially causing individuals to disengage from care or research. Trauma-informed practice emphasizes recognizing the prevalence of trauma, understanding its signs and symptoms, and actively resisting re-traumatizing individuals. This involves adapting practices to maximize a person's feelings of choice, collaboration, trust, empowerment, and safety.

Resource Allocation and Equity in Mental Health Emergency Response

The allocation of resources in mental health emergencies presents unique ethical challenges, particularly under conditions of scarcity. While general disaster triage often adopts a utilitarian approach to physical injuries, the principles of justice and equity remain critical for mental health services.

Resource scarcity can lead to ethical conflicts when the demand for healthcare overwhelms supply. In mental health, this translates to difficult decisions about who receives immediate or ongoing support. Various methods for resource allocation have been debated, including societal worth, first-come-first-served, or prioritizing based on the likelihood of short-term survival. The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina highlighted the severe lack of definitive guidelines for disaster triage, leading to morally distressing decisions about patient prioritization.

Ensuring equitable access to mental health services is crucial. This involves providing free or low-cost immediate support, such as crisis hotlines and walk-in centers, regardless of ability to pay. Federal and state programs aim to provide access to a network of mental health, substance use, and crisis support services, including for vulnerable populations like pregnant women, individuals with co-occurring disorders, and those with criminal justice involvement. Models like PsySTART aim to improve ethical resource management by providing rapid triage that can be done by non-mental health clinicians, allowing limited licensed professionals to focus on clinical assessments for those at highest risk.

The overarching goal is to ensure that mental health support is integrated into community disaster plans, addressing the needs of survivors, responders, and the broader community. This requires proactive planning and coordination among multidisciplinary teams and community providers.

Table 3: Ethical Principles and Dilemmas in Disaster Triage

Effectiveness, Outcomes, and Long-Term Resilience

The efficacy of psychological trauma triage and early interventions is a critical area of ongoing research, with findings indicating both immediate benefits and areas requiring further investigation regarding long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

Impact of Early Psychological Interventions on Acute Stress and Adaptive Functioning

Early psychological interventions, particularly Psychological First Aid (PFA), have demonstrated a positive impact on reducing acute stress reactions and facilitating adaptive functioning in the immediate and intermediate terms following traumatic exposure. PFA is designed to reduce initial distress and foster short- and long-term adaptive functioning and coping.

Studies evaluating PFA's effect on anxiety consistently show significant reductions. Among trials assessing anxiety levels in general trauma contexts, PFA frequently resulted in superior or comparable anxiety reduction compared to control groups or usual care. Similarly, single-cohort studies of adults in conflict zones or displaced populations found significant anxiety reduction after PFA intervention. Anxiety is noted as the most frequently assessed outcome indicator, consistently showing a significant reduction effect across various study designs.

Beyond anxiety, PFA has shown positive effects on other functional outcomes. Studies indicate improvements in quality of life, coping mechanisms, social support, and social adjustment following PFA interventions. Resilience and self-efficacy also demonstrated significant improvement in pre-post studies where PFA was delivered in mass trauma settings. PFA recipients have reported a heightened ability to be calm, help themselves and others, a greater sense of emotional control, improved functioning, and strengthened family relationships.

These findings underscore that early interventions, focusing on practical support and psychosocial strategies like PFA, are likely sufficient for the majority of individuals exhibiting mild to moderate distress or functional difficulties in the immediate aftermath of disaster events. This approach aligns with the objective of maximizing the natural resilience of affected individuals and communities and improving their coping abilities, thereby preventing the development of more severe mental health problems.

Evidence on Preventing Long-Term Mental Health Disorders (e.g., PTSD, Depression)

While PFA is effective in reducing acute distress and improving adaptive functioning in the short term , the evidence for its efficacy in preventing long-term mental health disorders such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms is less compelling. This observation highlights a gap between immediate crisis response and sustained mental health care.

Most people who experience psychological distress after emergencies will see their symptoms improve over time, with full recovery often occurring within 6 to 16 months. However, a significant minority may develop chronic problems like PTSD, depression, or substance abuse. Prevalence estimates for PTSD among direct victims can range from 30% to 40%, and 10% to 20% among rescue workers. For those who experience war or conflict, approximately 22% may develop depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia within 10 years.

For individuals whose distress persists or escalates beyond the acute phase, more intensive, formal mental health treatments are necessary. Empirically supported psychological treatments for PTSD include Prolonged Exposure (PE), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). These therapies have been tested in numerous clinical trials and are recommended for more severe or protracted reactions.

The limited conclusive evidence regarding PFA's long-term efficacy in preventing chronic conditions indicates that PFA alone is not a panacea. This suggests a critical need for integrated, stepped-care models where early interventions like PFA serve as a crucial first step, but clear pathways for escalation to more formal, evidence-based mental health services are established for those who require them. This continuum of care is essential to bridge the gap between immediate crisis response and sustained mental health recovery, ultimately aiming to reduce the societal burden of chronic mental health disorders following traumatic events.

Cost-Effectiveness of Psychological Trauma Triage Systems

Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of trauma triage systems is primarily discussed in the context of physical trauma, where rapid transport to specialized trauma centers for severely injured patients has shown a 25% reduction in mortality and is considered cost-effective under certain conditions. However, direct cost-effectiveness analyses specifically for

psychological trauma triage are less extensively detailed in the provided information.

General trauma triage guidelines aim for high sensitivity (identifying most serious injuries) and acceptable specificity (avoiding over-triage, which wastes resources). A high-sensitivity approach in physical trauma triage, while saving more lives, can be significantly more expensive per Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) gained compared to current practices. The most cost-effective approach for physical trauma triage appears linked to specificity and adherence to triage-based transport practices.

While specific cost-effectiveness data for psychological trauma triage systems like PsySTART or PFA is not explicitly provided in terms of QALYs or direct financial savings on long-term mental health care, the rationale for early intervention often implies cost-effectiveness through prevention. Early intervention for people at risk of developing mental health problems may reduce their severity, chronicity, and related long-term healthcare costs. By mitigating the development of serious mental disorders and supporting natural recovery, interventions like PFA can potentially reduce the need for more intensive, and thus more costly, formal mental health treatments in the long run.

The effectiveness of psychological treatments in general, particularly for patients with long-term physical conditions (LTCs), can be negatively impacted, suggesting that integrated care models are needed to improve outcomes and potentially cost-effectiveness in complex cases.

Fostering Individual and Community Resilience

A core objective of psychological trauma triage and early interventions is to foster resilience at both individual and community levels. Resilience, in this context, refers to the capacity of individuals and communities to adapt and recover from adversity.

Psychological First Aid explicitly aims to enhance natural resilience, rather than solely preventing long-term pathology. It promotes an environment that supports long-term recovery by helping people feel safe, connected to others, and empowered to help themselves. Key actions like promoting psychological safety, calming, self- and community efficacy, connectedness, and instilling hope are central to this process. Providing accurate information, encouraging positive coping, and connecting individuals to social support networks all contribute to building adaptive capacity.

At the community level, models like PsySTART contribute to understanding the "trauma temperature" of a population, allowing for targeted resource allocation that supports community-wide resilience. The Anticipate, Plan, Deter (APD) program for first responders is another example of fostering resilience through proactive planning and self-monitoring, ensuring the sustained capacity of the emergency response workforce.

Emergencies, despite the adversity they create, also present opportunities to invest in and build better mental health systems for the long term, leveraging increased aid and attention to develop improved care structures. This long-term perspective on resilience building is crucial for mitigating the enduring psychological impacts of disasters.

National Guidelines, Training, and Future Directions

The integration of psychological trauma triage into emergency response frameworks is increasingly recognized at national and international levels. This section reviews existing guidelines, current training initiatives, identifies persistent gaps, and proposes recommendations for future enhancements.

Overview of UK National Guidelines and Frameworks (NHS England, NICE)

In the United Kingdom, significant efforts have been made to integrate mental health and psychosocial care into emergency preparedness, resilience, and response (EPRR) frameworks. NHS England and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provide strategic guidance for managing major incidents and mass casualty events, including psychological aspects.

NHS England EPRR Framework: This national framework outlines principles for health emergency preparedness, resilience, and response for all NHS-funded organizations in England. It ensures that organizations meet requirements under relevant acts (e.g., Civil Contingencies Act 2004, NHS Act 2006) and adhere to NHS Core Standards for EPRR. The framework includes a "Concept of Operations for the Management of Mass Casualties," which details how NHS England establishes command and control for such incidents, specifying roles for ambulance, acute, community, mental health, and primary care providers. Plans for incidents and emergencies are mandated to provide psychosocial and mental healthcare for affected individuals, including NHS staff.

Emergency Response and Recovery Guidance (UK Government): This guidance aims to establish good practice based on lessons from UK and international emergencies, complementing "Emergency Preparedness." It emphasizes flexibility, tailoring responses to circumstances, and adhering to principles like anticipation, preparedness, subsidiarity, information management, coordination, cooperation, and continuity. Key groups covered include the injured, uninjured survivors, families, friends, specific vulnerable groups (children, elderly, faith groups), and rescue/response workers.

NICE Guidelines: NICE guidelines cover the rapid identification and early management of major trauma in pre-hospital and hospital settings, aiming to reduce deaths and disabilities. While primarily focused on physical trauma, they emphasize information and support for patients with major trauma and their families/carers. For mental health specifically, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) toolkit, revised in April 2021, recommends mental health triage by ED nurses on arrival to assess risk of self-harm, suicide, and absconding, and suggests using the Australian Mental Health Triage Tool. NICE also recommends "active monitoring" for the first month after an incident for short-term post-incident distress, meaning keeping a watchful eye on individuals.

Trauma-Informed Practice Frameworks: Regional NHS initiatives, such as the BNSSG (Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire) and Sussex frameworks, are developing shared language and approaches to trauma-informed practice. These frameworks acknowledge the prevalence of trauma, recognize its signs and symptoms, and aim to avoid re-traumatizing individuals. They emphasize principles like choice, collaboration, trust, empowerment, and safety, and recognize the impact of trauma on staff well-being.

Despite the increasing recognition of mental health needs in emergency response, a persistent gap often exists between high-level policy recommendations and the practical implementation of comprehensive, integrated mental health support and training for frontline responders. This suggests systemic barriers to effective mental health integration, which may include insufficient funding, lack of specialized training for non-mental health professionals, and the inherent challenges of coordinating diverse agencies in chaotic environments. Bridging this gap requires not only robust guidelines but also dedicated resources and sustained commitment to translating policy into actionable, widespread practice across all levels of emergency services.

Training Programs and Support for Emergency Services Personnel

Training and support for emergency services personnel are crucial for effective psychological trauma triage and for safeguarding the mental health of responders themselves.

Psychological First Aid (PFA) Training: PFA training is widely available, including online interactive courses that simulate post-disaster scenes. These courses teach core PFA actions, how to match interventions to stress reactions, and self-assessment for readiness. PFA is designed for use by first responders, incident command systems, primary and emergency healthcare providers, school crisis response teams, and various disaster relief organizations.

Mental Health First Aid (MHFA): Organizations like St John Ambulance provide MHFA training, equipping individuals with essential skills to identify early signs of mental health concerns, offer immediate support, and direct individuals to appropriate professional services. This training is recommended by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) for workplaces.

Specialized Responder Programs:

Anticipate, Plan, Deter (APD): This program, as discussed, focuses on pre-deployment resilience building and real-time self-triage for emergency personnel, integrating the PsySTART-R tool.

TRiM (Trauma Risk Management): Originating in the UK Armed Forces, TRiM is a trauma-focused peer support system for individuals exposed to traumatic events. Practitioners are non-medical personnel trained to spot signs of distress, conduct assessments, and signpost to support. TRiM managers coordinate responses and provide trauma awareness briefings. NICE guidelines suggest active monitoring for the first month after an incident, aligning with TRiM's "active monitoring" approach.

College of Paramedics Initiatives: The College of Paramedics emphasizes the increasing mental health caseload for paramedics and advocates for more education and training in mental health conditions, particularly in managing patients safely. They support joint working with mental health services and police in "street triage teams". The College also provides peer support programs for members facing Fitness to Practise complaints and promotes tools like the Mental Health Continuum for self-reflection and reducing stigma.

Suicide Prevention Training: The Zero Suicide Alliance offers free suicide prevention training to enable individuals to identify suicidal thoughts, offer support, and signpost to services.

Broader Support Networks: Partnerships like "Our Frontline" (Shout, Samaritans, Mind, Hospice UK, and The Royal Foundation) offer 24/7 confidential support for emergency responders.

Identified Gaps in Research and Practice

Despite advancements, several gaps persist in the research and practical implementation of psychological trauma triage:

Long-term Efficacy of Early Interventions: While PFA effectively reduces acute distress and improves adaptive functioning in the short term, the evidence for its long-term efficacy in preventing PTSD and depressive symptoms is less compelling. This indicates a need for more robust longitudinal studies on the preventative impact of early interventions.

Cost-Effectiveness Data: Formal cost-effectiveness analyses specifically for psychological trauma triage are limited. While the general principle of early intervention reducing long-term costs is acknowledged , detailed economic evaluations are needed to inform resource allocation decisions.

Implementation Science: There is a recognized need for better understanding of the optimal implementation of PFA and other early interventions. This includes research into variations in PFA format, timing, and delivery, as well as how to effectively integrate these interventions into existing emergency response structures.

Standardization vs. Local Adaptation: While national triage scales provide standardization, the need for local adaptation is also recognized. Research is needed to determine the optimal balance between universal guidelines and contextual flexibility to ensure both consistency and practical applicability.

Training Gaps for Frontline Responders: Despite the importance of mental health training, surveys indicate that paramedics, for example, do not always feel they possess the necessary skills and knowledge to meet the needs of mental health patients effectively. This highlights a need for more comprehensive and specialized mental health training tailored to the unique challenges faced by emergency personnel.

Moral Injury Research: While moral injury is increasingly recognized, further research is needed to fully understand its prevalence, long-term effects, and effective interventions specifically within emergency services.

Evidence-Based Disaster Protocols: The inherent difficulty in conducting randomized clinical trials in disaster medicine means there is no definitive data on which disaster triage technique would save the largest number of victims. This necessitates reliance on learning from past performances, simulation training, and mock drills.

Recommendations for Enhancing Psychological Trauma Triage

Based on the current understanding and identified gaps, several recommendations can be put forth to enhance psychological trauma triage in emergency response:

Integrate Psychological and Physical Triage Holistically: Develop and implement integrated training programs and protocols that ensure all emergency responders, from pre-hospital personnel to emergency department staff, are proficient in both physical and psychological triage principles. This fosters a comprehensive, interprofessional approach to trauma care from the outset.

Universal PFA Training: Mandate and standardize PFA training for all individuals involved in emergency response, including volunteers and community members. This broadens the reach of immediate psychological support, leveraging PFA's accessibility and non-pathologizing approach to build community-wide resilience.

Strengthen Stepped-Care Pathways: Establish clear and accessible pathways for individuals identified through early psychological triage to transition to more intensive, formal mental health services when needed. This ensures continuity of care and addresses the limitations of PFA in preventing long-term disorders for all individuals.

Invest in Data-Driven Triage Systems: Promote the adoption and further development of systems like PsySTART that utilize data analytics and GIS to provide real-time situational awareness of psychological impact at a population level. This enables more efficient, ethical, and equitable allocation of limited mental health resources.

Prioritize Responder Mental Health: Implement comprehensive, proactive resilience programs for first responders, such as the APD model, that include pre-incident training, individualized coping plans, and continuous self-monitoring. Address moral distress and moral injury through specialized support, peer networks, and leadership training to maintain the long-term well-being and operational capacity of emergency personnel.

Develop Contextually Flexible Guidelines: While striving for standardization, national guidelines should explicitly incorporate mechanisms for local adaptation to account for diverse operational realities, cultural nuances, and resource availability. This ensures practical applicability and optimal outcomes across varied emergency scenarios.

Advance Research on Long-Term Outcomes and Cost-Effectiveness: Fund and prioritize rigorous longitudinal studies to evaluate the long-term efficacy of early psychological interventions in preventing chronic mental health disorders. Conduct formal cost-effectiveness analyses to demonstrate the economic value of investing in comprehensive psychological trauma triage systems.

Enhance Training for Rapid, Non-Diagnostic Assessment: Develop and validate brief, observational psychological assessment tools suitable for rapid triage in high-stress environments. Train frontline personnel to use these tools effectively to identify immediate risks and distress, without requiring formal diagnostic capabilities in the acute phase.

Conclusion

Psychological trauma triage is an indispensable, evolving component of modern emergency response, extending the traditional focus on physical injury to encompass the profound and often enduring psychological impacts of traumatic events. The foundational principles of Psychological First Aid, emphasizing immediate support, safety, and connection, serve as a critical initial layer of intervention, accessible to a broad spectrum of responders. Advanced systems like PsySTART and proactive resilience programs such as APD demonstrate a growing sophistication in identifying population-level needs and supporting the mental well-being of frontline personnel.

However, significant challenges persist. The inherent ethical dilemmas of resource allocation in mass casualty incidents, particularly the tension between individual beneficence and utilitarian principles, create substantial moral distress and injury for healthcare providers. Furthermore, while early interventions effectively mitigate acute distress, conclusive evidence regarding their long-term efficacy in preventing chronic mental health disorders like PTSD remains an area requiring further rigorous research.

Moving forward, the field must prioritize a holistic integration of physical and psychological care, supported by universal PFA training, data-driven triage systems, and robust stepped-care pathways. Crucially, safeguarding the mental health of first responders through proactive resilience programs and addressing moral injury is paramount for sustaining effective emergency response capabilities. Continued investment in research, training, and adaptive guideline development will be essential to optimize psychological trauma triage, ultimately fostering greater individual and community resilience in the face of adversity.