Psychological and Long-Term Outcomes of Military Triage Decisions

Military triage, a critical process originating from battlefield necessity, involves the systematic sorting of casualties to optimize outcomes under conditions of scarce resources. While fundamentally designed to save lives and maintain combat effectiveness, the inherent nature of triage decisions profoundly impacts survivors, medical providers, and broader military operations.

Military triage, a critical process originating from battlefield necessity, involves the systematic sorting of casualties to optimize outcomes under conditions of scarce resources. While fundamentally designed to save lives and maintain combat effectiveness, the inherent nature of triage decisions profoundly impacts survivors, medical providers, and broader military operations. For survivors, the increased rate of survival from severe combat injuries, a testament to advancements in care, paradoxically leads to a higher prevalence of complex, chronic physical and psychological comorbidities, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and moral injury. These conditions present significant long-term challenges for personal well-being and social reintegration. Military medical providers face unique and often irreconcilable ethical dilemmas, particularly the conflict between universal medical impartiality and military objectives. This creates a "moral tragedy" for caregivers, leading to moral injury, burnout, and compassion fatigue. Operationally, triage decisions directly influence troop morale and unit cohesion, with perceived inequities undermining trust. The long-term health burden on the force necessitates a strategic shift towards comprehensive, integrated healthcare and robust support systems to sustain readiness and mitigate the enduring human cost of conflict.

Introduction to Military Triage

Definition and Historical Context of Military Triage

Triage, derived from the French word meaning “to sort,” is a foundational medical practice involving the categorization of casualties based on their immediate medical needs to prioritize treatment and evacuation. This systematic approach ensures that medical resources are allocated efficiently, particularly in scenarios where demand outstrips supply. Its origins are deeply rooted in military medicine, with its formalization often attributed to Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, a French surgeon during the Napoleonic Wars, who implemented a structured system for sorting wounded soldiers. This early military application underscored triage as a pragmatic and necessary response to the overwhelming number of casualties and limited medical capabilities inherent in armed conflict.

The historical trajectory of triage from a military imperative to a widely adopted civilian practice highlights its fundamental utility in managing resource scarcity. The principles developed on the battlefield, where medical capacity is rapidly exceeded by the number of wounded, have been adapted for civilian mass casualty incidents, such as natural disasters or pandemics. This widespread adoption demonstrates that the core tenets of military triage, often perceived as austere, are not unique to combat but represent a universally applicable, albeit adapted, strategy for optimizing outcomes when medical resources are severely constrained. The military context simply presents this challenge in its most extreme form, necessitating a utilitarian approach focused on the "greatest good for the greatest number," a principle that also guides civilian disaster response.

Core Principles and Objectives of Tactical Triage

The primary goals guiding military triage are multifaceted: to achieve "the greatest good for the greatest number of casualties," to ensure "the most efficient use of available resources," and critically, to "return personnel to duty as soon as possible". This last objective introduces a strategic imperative that distinguishes military triage from conventional civilian medical ethics, which typically prioritizes the most severely wounded regardless of non-medical factors.

Triage becomes particularly crucial in Mass Casualty (MASCAL) situations, defined by the number of casualties overwhelming the available medical capacity for rapid treatment and evacuation. Such scenarios demand rapid critical thinking and the efficient prioritization of both personnel and resources. The explicit military objective of returning personnel to duty introduces a significant ethical dimension. This can lead to a practice known as "reverse triage," where individuals with less severe injuries are prioritized for treatment to facilitate their rapid re-engagement in combat, directly contrasting with the civilian principle of treating the "sickest first". This strategic imperative creates a profound ethical tension, as it can necessitate decisions that deviate from standard medical principles, emphasizing that military triage is not solely a medical act but a complex operational decision with direct implications for force strength and mission success.

Overview of Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Phases and Triage Integration

Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) provides a structured framework for medical response in combat environments, delineating three distinct phases of care: Care Under Fire/Threat, Tactical Field Care, and Tactical Evacuation Care. Triage is dynamically integrated across these phases, adapting to the evolving tactical situation and available resources.

In the Care Under Fire phase, formal triage is generally deferred due to the immediate and active threat. The paramount priorities are threat suppression, moving casualties to cover if feasible, and immediate control of massive hemorrhage, often through self-aid or buddy-aid. This phase involves an implicit, rapid assessment of immediate life threats, but a comprehensive triage process is impractical given the tactical environment.

The Tactical Field Care phase commences when direct enemy fire has ceased, allowing for a more thorough assessment and treatment. Triage is explicitly the second step in this phase, indicating a formal and deliberate process of categorizing casualties. Medics perform a rapid initial assessment, ideally within one minute per patient, and prioritize interventions based on "Circulation, Breathing, Airway" (CBA) rather than the traditional "ABC" (Airway, Breathing, Circulation) due to the high prevalence of massive bleeding in combat trauma. This reversal reflects a pragmatic adaptation to maximize survivability in a combat context.

During Tactical Evacuation Care (TACEVAC), which encompasses both Casualty Evacuation (CASEVAC) and Medical Evacuation (MEDEVAC), triage continues as an ongoing reassessment process while casualties are transported to higher elevel of medical care. This includes re-triaging casualties as their conditions may deteriorate or improve, and utilizing advanced diagnostic equipment when available. The phased and iterative nature of triage within TCCC, particularly the shift from immediate life-saving actions under fire to formal assessment and continuous re-evaluation, demonstrates a highly adaptive and context-dependent medical strategy. This dynamic approach, coupled with the CBA priority reversal, reflects a pragmatic system designed to maximize survivability and operational effectiveness in chaotic and resource-limited combat environments. This continuous decision-making process, while optimizing physical outcomes in the short term, can contribute to sustained cognitive load and moral strain on medical providers.

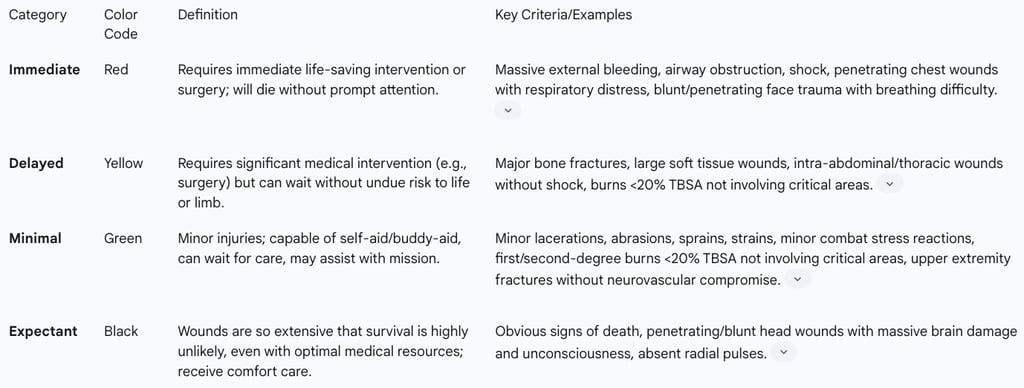

Description of Military Triage Categories

Military triage sorts casualties into four distinct, color-coded categories to facilitate rapid segregation, treatment, and evacuation prioritization. The physiological state of the patient, rather than solely the type or extent of the wound, is the critical determinant for categorization.

Immediate (Red Tag): These casualties represent the highest priority, requiring immediate life-saving interventions (LSIs) or surgery. Without prompt medical attention, their survival is unlikely. Examples include massive external bleeding requiring a tourniquet, airway obstruction, or patients in shock. The key to successful triage is to locate these individuals as quickly as possible.

Delayed (Yellow Tag): Casualties in this category require significant medical intervention, potentially including surgery, but their condition is stable enough to allow for a delay in treatment without unduly endangering life or limb. They may need interventions such as splinting or pain control that can wait. Examples include major bone fractures, large soft tissue wounds, or intra-abdominal/thoracic wounds without evidence of shock.

Minimal (Green Tag): Often referred to as the "walking wounded," these patients have minor injuries such as small burns, lacerations, abrasions, or minor fractures. They are capable of self-aid or buddy-aid and can often be utilized for mission requirements like scene security while awaiting medical care.

Expectant (Black Tag): This category includes casualties with wounds so extensive that their survival is highly unlikely, even with optimal medical resources. While de-prioritized for aggressive medical intervention, they should still receive comfort measures and pain medication. Examples include penetrating or blunt head wounds with obvious massive brain damage and unconsciousness, or those with absent radial pulses.

The explicit definition of the "Expectant" category is a stark manifestation of the "greatest good for the greatest number" principle in military triage. This deliberate de-prioritization of lives deemed unsalvageable, while pragmatically necessary in resource-limited environments, represents a profound source of moral injury for medical providers. For providers, this categorization can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, and moral distress. For survivors, the awareness of this category or witnessing its application can trigger survivor's guilt or a profound questioning of their own value and the system's priorities.

Table 1: Military Triage Categories and Criteria

Psychological and Long-Term Outcomes for Military Personnel (Survivors)

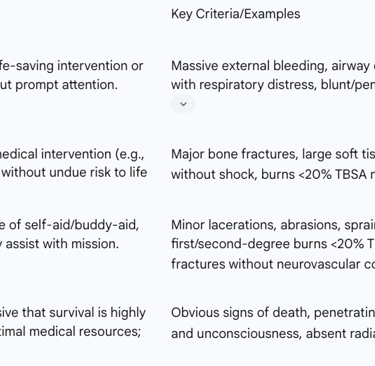

Prevalence and Types of Mental Health Conditions

Combat-injured service members exhibit significantly higher incidence rates of mental health conditions compared to their non-injured counterparts. Data indicates increased rates of PTSD (17.1% vs. 5.8%), depression (10.4% vs. 5.7%), and anxiety (9.1% vs. 4.9%) among combat-injured patients. These pervasive psychological challenges stem from a confluence of factors inherent to military service, including direct combat exposure, prolonged deployments, and the intense, unpredictable stressors of military life.

Beyond the widely recognized diagnoses of PTSD, depression, and anxiety, veterans also face elevated risks of adjustment disorders, substance abuse (affecting more than one in ten veterans), and tragically, increased suicide rates. A particularly salient development in modern combat medicine is the increased survivability of severe injuries, especially those resulting from blast mechanisms like improvised explosive devices (IEDs), which often lead to traumatic brain injury (TBI) and polytrauma (multiple injuries). While this enhanced survival is a testament to advancements in personal protective equipment and combat casualty care, it concurrently contributes to a higher prevalence of complex, chronic psychological and physical comorbidities. This phenomenon often manifests as the "polytrauma clinical triad," a concerning co-occurrence of TBI, PTSD, and chronic pain. This intricate relationship implies that the success of battlefield triage in preserving lives shifts the burden from immediate mortality to a long-term, integrated healthcare challenge. This necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of post-combat support systems and a sustained focus on comprehensive, life-long care, recognizing that the battle for well-being continues long after the physical wounds have healed.

Specific Psychological Impacts Related to Triage Decisions

The very act of being subjected to triage decisions, or witnessing them, can itself be a distinct form of trauma, leading to specific psychological outcomes that extend beyond general combat exposure.

Survivor's Guilt is a prevalent emotional and often visceral response among military personnel, characterized by profound feelings of guilt and persistent questions such as "Why did I survive when others didn't?". This is particularly acute due to the intense bonds formed within military units and the shared exposure to high-intensity combat situations. Survivor's guilt frequently manifests alongside grief and loss, often intertwining with symptoms of PTSD.

Moral Injury, distinct from PTSD, is defined as the lasting emotional, psychological, social, behavioral, and spiritual impacts resulting from actions (of commission or omission) or witnessing events that profoundly contradict deeply held moral beliefs and values. In the context of triage, this can occur when medics are unable to provide care to all who are harmed due to resource limitations, or when officers are compelled to make life-or-death decisions that directly affect the survival of others. Hallmark symptoms of moral injury include intense guilt, shame, disgust, anger, an inability to self-forgive, and a significant impact on one's spirituality.

The Impact of Being Triaged as "Expectant" but Surviving presents a unique psychological challenge. While direct survivor accounts of this specific experience are not extensively detailed, the available information indicates that the "aftereffects of triage-like situations are often insidious and may remain hidden for years, sometimes expressing themselves somatically, psychologically, and behaviorally". For an individual categorized as "beyond help" but who ultimately survives, this experience can lead to traumatic flashbacks, feelings of "unconscious or dissociated survivor guilt or shame," and a fundamental challenge to their sense of self and core values. The process of battlefield medical care, particularly the inherent moral compromises and resource limitations of triage, is therefore a significant, and often overlooked, determinant of long-term mental health for survivors. The triage process, by its very nature of sorting and prioritizing, establishes a hierarchy of perceived worth and can involve the perceived abandonment of some individuals (the "Expectant" category). This process can inflict a "moral wound" on those who survive, or who witness others being de-prioritized, leading to deep existential distress. This necessitates psychological support specifically tailored to the unique trauma of triage experiences.

Long-Term Physical Health Consequences and Their Interplay with Psychological Well-being

Combat injuries, particularly those resulting from explosive mechanisms like improvised explosive devices (IEDs), frequently lead to polytrauma, encompassing a range of physical injuries to limbs, concussion, traumatic brain injury (TBI), burns, blinding, and hearing loss. A significant and concerning co-occurrence among combat-injured veterans is the "polytrauma clinical triad" of TBI, PTSD, and chronic pain. A study at one Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) polytrauma site found that 42.1% of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans were diagnosed with all three conditions. This triad is further associated with other adverse health outcomes, including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and obesity.

Veterans consistently report chronic physical health conditions as a top concern immediately after military service, sometimes even surpassing concerns about work or social relationships. This high prevalence and comorbidity of the "polytrauma clinical triad" reveal a complex and bidirectional relationship between physical and psychological health. Triage decisions, by enabling survival from severe physical trauma, directly contribute to this long-term, integrated health challenge, where physical pain can exacerbate mental distress, and psychological conditions can impede physical recovery. Despite these significant health issues, some veterans exhibit a reluctance to seek medical treatment for physical health difficulties, which can pose additional challenges for their informal caregivers. The success of military triage in preserving lives means that military healthcare systems must now manage a population with enduring, complex health needs that defy simple categorization. This necessitates a holistic and integrated approach to veteran care, recognizing that physical and mental health are inextricably linked.

Social Reintegration Challenges for Survivors

Returning military service members and veterans (MSMVs) face substantial hurdles in transitioning back to civilian life. These challenges include adapting to family dynamics, entering the civilian workforce, and navigating non-military social environments. Common difficulties reported include emotional disconnection from family and friends, struggles with managing intense emotions such as anxiety and alienation, a profound sense of loss for military life, and persistent negative effects of deployment on daily functioning, such as sleep disturbances and difficulty securing employment.

Even veterans without formal mental health diagnoses report significant difficulty (25% or more) in social functioning, self-care, or other major life domains post-deployment. These challenges can escalate into serious issues such as relationship problems, employment instability, homelessness, and an increased risk of suicide. Family members of service members also experience considerable distress and challenges during the reintegration process, including psychological and relationship problems, and may assume increased caregiving responsibilities for injured service members.

The pervasive and multifaceted challenges of social reintegration, compounded by the physical and psychological injuries sustained in combat, reveal a critical gap between battlefield survival and successful civilian life. Triage decisions, by preserving lives, contribute to a population that requires extensive, long-term societal and systemic support to overcome not only their physical and psychological wounds but also the profound cultural and social disconnections that hinder their return to normalcy. The success of triage in saving lives means that military healthcare systems must now manage a population with enduring, complex health needs that defy simple categorization. This necessitates a holistic and integrated approach to veteran care, recognizing that physical and mental health are inextricably linked.

Table 2: Key Psychological Outcomes for Military Personnel (Survivors)

Psychological and Ethical Burdens on Military Medical Providers

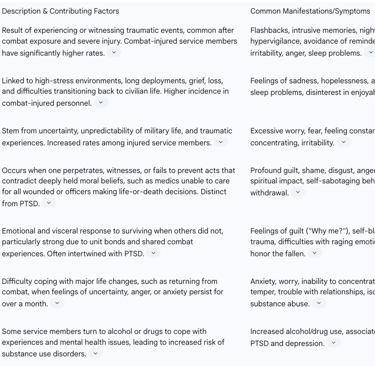

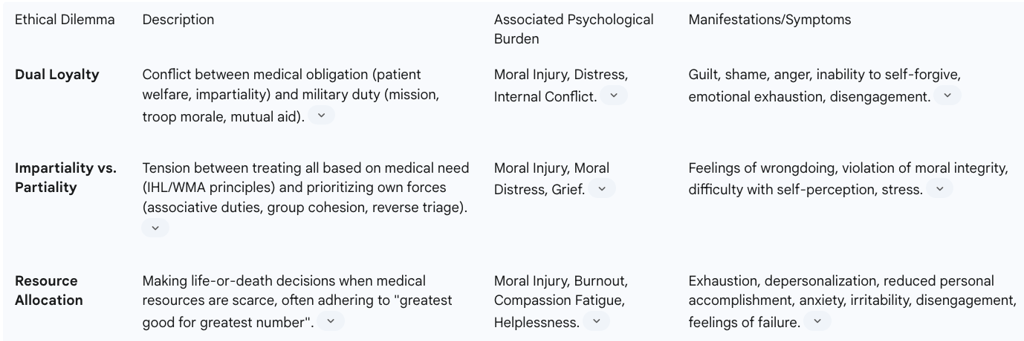

Ethical Dilemmas Inherent in Military Triage

Military medical personnel operate within a complex ethical landscape, facing dilemmas that are often unique to the combat environment. A central challenge is the pervasive dual loyalty dilemma, where providers are caught between their fundamental ethical obligations as medical professionals (e.g., prioritizing patient welfare, impartiality) and their duties as military officers (e.g., supporting the mission, maintaining troop morale, providing mutual aid to compatriots). This inherent conflict frequently results in significant distress for the individual provider.

The principle of impartiality versus partiality presents another profound ethical challenge. Conventional medical ethics, as codified in International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and declarations by organizations like the World Medical Association (WMA), mandates impartial treatment based solely on medical need, without discrimination based on nationality, race, or other non-medical criteria. However, in battlefield triage, the question arises whether prioritizing one's own soldiers—based on "associative duties" or the ethics of "small group cohesion"—is ethically permissible or even required by the military context. This tension can lead to practices like "reverse triage," where less severely wounded personnel are treated first to enable their rapid return to duty, directly conflicting with the "sickest first" principle.

Triage, by its very definition, involves the allocation of scarce resources when demand for medical care exceeds supply. This necessitates difficult decisions about who receives treatment and who does not, often adhering to the principle of "doing the greatest good for the greatest number". This utilitarian approach can mean de-prioritizing individuals who might otherwise be saved in a resource-rich environment, creating a profound ethical burden.

The inherent and often irreconcilable conflict between universal medical ethics (impartiality, individual patient focus) and military imperatives (mission success, group cohesion, resource scarcity) places military medical providers in a unique and profoundly challenging ethical bind. This situation has been characterized as a "moral tragedy". This means there is no "blameless" decision, and critical values must be sacrificed, leading to significant moral residue and distress. Even when a physician makes a defensible choice, such as prioritizing their own soldiers, it still involves sacrificing other important values like justice, compassion, and respect for others. This underscores the importance of specialized ethical training that prepares them for this unavoidable reality and provides frameworks for coping with moral residue, rather than implying a "right" and blameless path always exists.

Psychological Distress Experienced by Providers

Military medical personnel, including nurses, face a high risk for adverse psychological effects due to chronic exposure to trauma, death, violence, threats to personal safety, and the constant navigation of ethical dilemmas in austere environments.

Moral Injury is a significant psychological burden for healthcare workers, particularly in military settings. It arises when they are compelled to make difficult life-and-death triage decisions, allocate scarce resources, or perceive a failure to save a patient they believed they should have. This stems from acting or witnessing behaviors that violate their deeply held moral beliefs. Symptoms include profound guilt, shame, disgust, anger, and an inability to self-forgive. The direct conflict between professional ethics and operational necessity, particularly in triage, is a primary driver of moral injury for medics.

Burnout and Compassion Fatigue are common consequences of chronic, unmanaged workplace stress, particularly prevalent in care-rendering professions. The immense pressure to treat high numbers of patients with limited resources in triage situations significantly contributes to these conditions. Symptoms include emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, reduced personal accomplishment, anxiety, irritability, disengagement, and a decline in physical and mental health. The psychological distress experienced by military medical providers is a direct and severe consequence of the moral burden imposed by triage decisions in resource-scarce, high-stakes environments. They are forced into situations where their core medical values are challenged, leading to profound internal conflict and chronic stress. This effectively positions them as "secondary victims" of the battlefield's ethical landscape.

The Concept of "Moral Tragedy" in Battlefield Triage

The framing of battlefield triage as a "moral tragedy" provides a crucial conceptual framework for understanding the profound and often intractable nature of provider psychological outcomes. This concept moves beyond simply labeling experiences as "stress" or "difficult decisions" to acknowledge an inherent, unavoidable ethical cost that cannot be eliminated by perfect training or unlimited resources. A "moral tragedy" signifies that there is "no morally blameless decision" and that "justice is unattainable". This means the physician will inevitably sacrifice core values such as justice, compassion, and respect for others, regardless of the choice made, and will experience grief and distress as a result. This is not a failure of the individual but an inherent characteristic of the situation itself.

This understanding shifts the focus from finding a "right" answer to acknowledging the inherent ethical burden and preparing providers to cope with unavoidable moral distress. It suggests that psychological interventions for military medics must validate their moral suffering, provide tools for self-forgiveness (where applicable), and foster resilience in the face of morally ambiguous realities, rather than simply treating symptoms of fear-based trauma. This also highlights the importance of organizational support that recognizes and legitimizes this unique form of suffering.

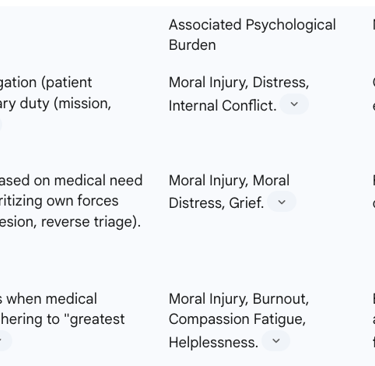

Table 3: Ethical Dilemmas and Psychological Burdens for Medical Providers

Impact on Military Operations

Morale and Unit Cohesion

The effectiveness of military medicine and the perceived fairness of triage decisions directly influence troop morale and unit cohesion. Research indicates that military personnel who believe they may not be prioritized for medical care, particularly in scenarios involving the prioritization of mission-essential personnel, report significantly lower levels of morale. This finding aligns with the understanding that a soldier's willingness to fight and follow orders is significantly bolstered by the assurance of adequate medical support in case of injury.

Military medicine, by improving survivability, plays a crucial role in preserving military units and preventing the erosion of morale that can result from the death, illness, or injury of close friends within a unit. This preservation fosters prolonged contact and shared experiences among soldiers, which are vital components of unit cohesion. However, perceived inequities in triage, such as those arising from "reverse triage" protocols, can undermine this sense of security and mutual care within the group, potentially impacting military effectiveness. The relationship between military medicine and morale is complex, with investments in medical care contributing to overall effectiveness by improving morale and strengthening the bonds that drive soldiers to fight for their comrades.

Strategic Objectives and Resource Allocation

Triage is a critical component of military resource allocation, directly impacting strategic objectives, especially in mass casualty scenarios. Its core purpose is to achieve "the greatest good for the greatest number" of casualties, thereby optimizing the use of limited medical resources to maintain combat effectiveness. This principle is fundamental to preventing medical systems from being overwhelmed and ensuring that the maximum number of personnel can contribute to the mission.

In certain tactical scenarios, "reverse triage" may be employed, where lightly wounded personnel are prioritized for rapid treatment and return to duty. This practice, while potentially conflicting with individual medical needs, serves the strategic objective of rapidly reconstituting fighting strength and achieving mission success. The ability to deliver high-level medical care quickly, often within the "Golden Hour" post-injury, and to effectively manage prolonged casualty care, significantly impacts strategic victory, particularly in large-scale combat operations (LSCO). This highlights the direct and undeniable link between medical decisions made at the tactical level and the broader operational success of military forces. Effective triage and casualty management are therefore not merely humanitarian concerns but integral to military strategy and force projection.

Long-Term Force Health Protection and Readiness

The remarkable advancements in combat casualty care, including sophisticated triage protocols, have led to unprecedented survival rates for service members who sustain severe injuries. While this is a significant achievement, it creates a long-term burden of complex physical and psychological conditions, notably polytrauma, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This shift necessitates a fundamental re-orientation in military healthcare, moving beyond acute trauma response to comprehensive post-combat support, health promotion, and disease prevention to maintain long-term force readiness.

The "invisible wounds of war," such as TBI, PTSD, and depression, significantly impact future clinical care challenges and overall combat readiness. These conditions can lead to substantial lost duty days, comparable to or even exceeding those caused by battle injuries, thereby degrading the overall fighting strength of the military. Therefore, the success of triage in saving lives in the short term necessitates robust, integrated, and sustained long-term health system support. Without adequate investment in managing these chronic conditions and facilitating effective social reintegration, the military risks a degradation of its long-term operational capacity and the well-being of its personnel. Ultimately, military medicine's ability to strive for peak performance, maximize survival rates, and ensure the highest potential functional recovery underpins the trust service members, their families, and citizens place in the military healthcare system.

Conclusions

Military triage decisions, while vital for optimizing outcomes in the chaotic and resource-constrained environment of combat, exert profound and multifaceted psychological and long-term impacts on survivors, medical providers, and military operations. The evolution of triage from a battlefield necessity to a universal principle for managing mass casualties underscores its pragmatic utility in situations where demand for medical care exceeds supply.

For survivors, the increased survivability of severe combat injuries, a direct outcome of effective triage and advanced medical care, has led to a higher prevalence of complex, chronic physical and psychological comorbidities. The "polytrauma clinical triad" of TBI, PTSD, and chronic pain exemplifies this enduring burden, necessitating a shift towards comprehensive, integrated healthcare that addresses the intricate interplay between physical and mental well-being. Furthermore, the very experience of being triaged, or witnessing such decisions, can inflict unique psychological wounds such as survivor's guilt and moral injury, demanding specialized support that acknowledges these distinct forms of trauma. The pervasive challenges of social reintegration, encompassing family dynamics, employment, and cultural adaptation, highlight a critical gap between battlefield survival and successful civilian life, underscoring the need for extensive, long-term societal and systemic support.

Military medical providers bear immense psychological and ethical burdens. They are frequently caught in a "dual loyalty" dilemma, navigating the inherent conflict between universal medical ethics—which mandate impartial care based solely on medical need—and military imperatives, such as prioritizing mission success or the lives of their own comrades. This often leads to a "moral tragedy," a situation where no decision is entirely blameless, forcing providers to sacrifice deeply held values and resulting in profound moral injury, burnout, and compassion fatigue. The psychological toll on these caregivers is not merely a consequence of witnessing horrific events but is deeply rooted in the moral compromises and impossible choices inherent in their professional role.

Operationally, triage decisions directly influence military effectiveness. Perceptions of medical care prioritization significantly impact individual morale and unit cohesion; a belief that one might not be prioritized for care can erode trust and willingness to fight. Conversely, effective military medicine, by increasing survivability, strengthens unit bonds and prevents morale erosion. The strategic objective of triage, particularly in utilizing "reverse triage" to return lightly wounded personnel to duty, directly supports combat effectiveness and the achievement of mission objectives. However, the long-term health consequences of combat injuries, including the "invisible wounds of war," present a significant challenge to sustained force readiness, emphasizing that short-term medical success must be complemented by robust, long-term force health protection strategies.

In conclusion, military triage, while a cornerstone of battlefield medicine, carries profound and enduring human costs. A holistic approach is essential, one that not only continually refines medical protocols but also prioritizes comprehensive psychological support for both survivors and providers, invests in long-term reintegration programs, and acknowledges the complex ethical landscape within which military medical decisions are made. This integrated understanding is critical for mitigating the adverse psychological and long-term outcomes and for ensuring the sustained health and readiness of the military force.