Italian Emergency Department Triage System: Regional Variations and the Evolution from 4-Level to 5-Level Models

The Italian emergency department, known as the Pronto Soccorso, operates on a priority-based system rather than a first-come, first-served model. This system, known as triage, is the critical first assessment and sorting process that determines a patient’s urgency and, consequently, their priority for medical care.

The Italian emergency department, known as the Pronto Soccorso, operates on a priority-based system rather than a first-come, first-served model. This system, known as triage, is the critical first assessment and sorting process that determines a patient’s urgency and, consequently, their priority for medical care. The fundamental purpose of triage is to ensure that patients with life-threatening conditions receive immediate and timely treatment, thereby avoiding dangerous delays. This process is dynamic and is carried out by a highly trained nurse upon the patient’s arrival at the hospital.

The concept of triage itself is not a modern invention but has its roots in military medicine, where it was developed to manage a high volume of casualties with limited resources. The term "triage" is French in origin, translating to "to choose" or "to sort," and its initial application is credited to French military surgeons like Dominique Jean Larrey during the Napoleonic Wars. Early forms of this system were used in Italy as far back as 1848 by Field Marshal Josef Wenzel Graf Radetzky. Its transition into the civilian healthcare sector in Italy began after World War II, but it did not become a mainstream standard in emergency departments until the late 1980s. A key event that spurred the need for a national, coordinated emergency system was the 1980 Bologna train station massacre, which led to the official establishment of the national "118" emergency service in 1992.

Despite the national mandate for emergency services, the Italian triage system is characterized by a significant degree of regional fragmentation, a direct outcome of the nation's decentralized healthcare governance. The Servizio Sanitario Nazionale (SSN), Italy's National Health Service, is highly decentralized, with legislative and executive powers devolved to the country's twenty regions, five of which have special autonomous status. This devolution of power, which has been in place since the SSN's creation in 1978 and was further amplified by a 2001 constitutional reform, grants each region the independence to define its own healthcare priorities and operational goals. Consequently, there is no single, unified triage system that is standard across all Italian emergency departments; instead, each department or region may employ its own method, often with limited supporting scientific evidence on a national scale. This structural reality creates a direct link between Italy's political-administrative framework and the variability of its clinical-operational practices, making the analysis of triage an examination of the broader public policy landscape.

Core Triage Models and Their Clinical Criteria

The Italian emergency department triage system is primarily defined by two models: a traditional 4-level color-coded system and a more modern 5-level system. The shift between these models represents a strategic evolution in response to mounting systemic pressures, particularly the challenge of managing patient flow and resource allocation in increasingly crowded environments.

The Traditional 4-Level Color-Coded System

The 4-level system is a long-standing model that categorizes patients into four distinct levels of urgency, each represented by a specific color code.

Red (Codice rosso): This code is reserved for life-threatening emergencies where one or more vital functions are severely compromised or interrupted. Patients assigned a Red code receive immediate access to care, with no waiting time.

Yellow (Codice giallo): This signifies a critical but stable condition with a high level of risk or a potential threat to vital functions. Treatment for Yellow code patients cannot be delayed.

Green (Codice verde): This code is for minor injuries or illnesses. Patients with a Green code are considered to have a minor urgency and a stable condition with no risk of worsening, and their treatment can be delayed.

White (Codice bianco): The White code is for non-urgent problems of minimal clinical relevance. These cases could typically be managed by a general practitioner in an outpatient setting and are considered non-critical. In some cases, patients with a White code may be subject to a co-payment fee.

Under this system, patient wait times are directly correlated with their assigned color code. While Red codes receive immediate attention, non-urgent White or Green code patients can face long waits, sometimes exceeding 5 or 6 hours in busy urban centers. Official wait time guidelines stipulate that non-urgent cases can have a maximum wait time of 240 minutes, or 4 hours.

The Modern 5-Level Color-Coded System

The transition to a 5-level system was a response to the limitations of the 4-level model, which struggled to adequately differentiate between the large volume of non-critical patients. The introduction of an intermediate category provides a more granular scale for prioritizing patients and managing resource flow. A common 5-level model in Italy is structured as follows:

Red (Codice rosso): This code remains the highest priority for life-threatening emergencies, with immediate access to treatment.

Orange (Codice arancione): This is a new level of urgency for patients with a high risk of losing vital functions or experiencing severe pain. Patients with an Orange code are targeted to be seen within 15 minutes.

Light Blue (Codice azzurro): This code signifies a deferrable urgency for a stable patient who requires complex services or diagnostic tests. The target wait time for this category is 60 minutes.

Green (Codice verde): This code is now for a minor urgency that requires simple diagnostic or therapeutic services. Wait times are targeted at 120 minutes.

White (Codice bianco): This category remains for non-urgent problems, with a maximum wait time of 240 minutes.

This evolution from a 4-level to a 5-level system is a direct attempt to refine patient sorting by introducing a new, intermediate category. The goal is to separate patients who are at a higher but not immediate risk (Orange/Light Blue) from the large cohort of minor cases (Green), thereby improving the efficiency of patient flow and better directing medical resources. Studies evaluating this shift have shown a decreased trend in undertriage, suggesting the new system is more effective at identifying and appropriately prioritizing urgent cases. However, this improvement in safety for critical patients may come with a slight increase in overtriage, where a patient is assigned a higher priority level than their condition warrants. This introduces a new set of challenges, as this "triage creep" may inadvertently contribute to longer processing times for lower-acuity cases and continued ED crowding, a finding that is not universally agreed upon in the literature.

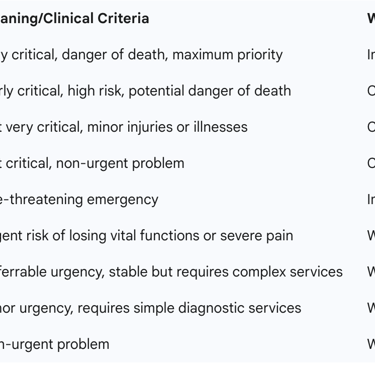

The table below provides a comparative overview of the two systems.

Analysis of Regional Variations in Practice: Case Studies

The regional autonomy embedded in Italy's healthcare system has resulted in a fragmented landscape where different regions have developed and implemented their own unique triage models and protocols. This decentralized approach is a double-edged sword, fostering local innovation while simultaneously contributing to significant national variability and, in some cases, inequity.

Tuscany: A Model of Local Innovation

The Tuscany region has actively innovated its emergency system, exemplified by the development of the "Tuscan Triage System" (TTS). A validation study of the TTS demonstrated its safety and effectiveness, showing good inter-rater reliability among nurses and a high adherence to reference standards for the most critical triage levels. The TTS was specifically designed to apply a new organizational framework that included low-priority streaming, and a comparison with the previous regional system revealed a notable shift towards the assignment of lower priority codes. This regional initiative showcases how local governance can create specialized, evidence-based solutions to address specific operational needs.

Lazio: A Focus on Specialized Patient Groups

In the Lazio region, the "Triage Model of Lazio" (TML) has proven particularly effective in managing a complex patient demographic: individuals with mental health needs. Research indicates that nurses who utilized the TML were significantly less likely to perceive psychiatric patients as "hostile, aggressive, and unpredictable" and demonstrated a greater capacity for their proper clinical management. The TML's success highlights the value of specialized, integrated knowledge and skills for nurses working with vulnerable patient populations, demonstrating how a regional model can address a specific clinical and social challenge.

Lombardy: A Pioneer in Trauma Triage

The Lombardy region, one of the first in Italy to develop a comprehensive trauma system, has been at the forefront of pre-hospital triage innovation. A prospective study conducted in Milan validated the TRENAU triage tool for trauma patients, finding it to be highly effective. When compared to the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT) scheme, the TRENAU score demonstrated a moderately good accuracy with a significantly lower overtriage rate of 23% and an acceptable undertriage rate of 3.9%. This regional effort illustrates how a tailored, data-driven approach can optimize resource utilization while maintaining patient safety, leading to a recommendation for the adoption of the TRENAU score within Lombardy’s trauma system.

The varied and innovative solutions developed in Tuscany, Lazio, and Lombardy underscore the potential benefits of regional autonomy. However, this same autonomy is at the heart of a significant national disparity. While affluent northern regions like Lombardy can develop sophisticated, specialized systems, public facilities in the southern regions are often described as "more basic". This disparity in healthcare quality and accessibility has led to a "massive movement of people from south to north" in search of better and faster services. The geographical inequalities in healthcare are a well-documented national problem, with evidence showing that residents in regions with higher poverty and unemployment rates report poorer health. The decentralized governance structure, which allows for local innovation in one area, directly contributes to and reinforces this north-south "structural fracture," compromising equitable access to care across the country. The fragmentation of standards, therefore, is not merely an inconvenience but a fundamental issue of social and health inequity.

Systemic Challenges and Performance Metrics

The fragmented nature of Italian triage, coupled with increasing patient demand, presents several systemic challenges that compromise both efficiency and patient safety. Analyzing these challenges provides a critical perspective on the urgent need for reform.

The Impact on Patient Safety

A primary concern stemming from the lack of a national standard is the high degree of subjectivity in triage code assignment by nurses. A multicenter simulation study involving hospitals in Bolzano, Merano, Pisa, and Rovereto found "marked variation" in triage codes assigned by nurses, with inter-rater reliability scores (Kappa values) ranging from 0.464 to 0.632. This suggests a fundamental inconsistency in how severity is assessed, which can lead to incorrect patient classifications, including both under-triage and over-triage. Under-triage—the underestimation of a patient’s condition—is particularly dangerous, as it can result in increased safety risks and delayed care for critically ill patients. One study specifically highlighted an under-triage rate of 3.2% in an Italian pediatric setting, which was noted to be higher than the rate reported in the scientific literature.

Triage and Hospital Crowding

Hospital crowding is a pervasive problem in Italian emergency departments, especially in big cities like Rome, where long lines and slow service are a common occurrence. Crowding is a multifaceted issue driven by a confluence of factors, including a high influx of patients, a greater number of complex cases, and internal operational bottlenecks like "exit block"—the inability to move admitted patients out of the ED in a timely manner.

The transition from a 4-level to a 5-level triage system was, in part, a strategic response to this crowding. The introduction of an intermediate urgency code, such as Orange, was intended to better distribute patients and resources. While studies have shown that the 5-level system can improve ED performance and patient care by reducing under-triage, a review of the literature reveals conflicting results regarding its impact on wait times, with some sources claiming improvements and others noting a lengthening of waits. This suggests that a new triage system alone is not a panacea for the complex issue of crowding. The design of a triage system introduces a subtle trade-off: while a 5-level system may be better at identifying and appropriately prioritizing urgent cases, it may also lead to a slight increase in over-triage by assigning a higher acuity level to patients than necessary. This can potentially exacerbate wait times for less urgent patients and contribute to the very crowding issues the system was designed to mitigate.

Triage in Crisis: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a critical stress test for the Italian healthcare system, exposing the inherent fragilities of its decentralized, fragmented structure. The rapid and overwhelming surge of cases, particularly in northern Italy, made the concept of triage widely known to the public and forced hospitals to confront the grim reality of resource scarcity. Without a single, nationally mandated protocol, doctors faced unprecedented ethical dilemmas. The Italian society of anesthesiologists was compelled to issue recommendations for a "wartime triage" approach, where decisions would be based on a patient's "best chance of survival" rather than the standard "first come, first served" egalitarian model.

This ethical vacuum, created by the absence of a national framework, led to a chaotic and subjective situation at the hospital level. Reports from northern Italy revealed that triage practices varied significantly from one hospital to another, with age cut-offs for intensive care unit (ICU) admission dropping to as low as 75 or even younger at the peak of the epidemic. This lack of a transparent, national standard placed immense moral and legal pressure on physicians, and the absence of clear guidelines created a situation where life-and-death decisions were made with immense subjectivity, leading to public anguish and legal uncertainty. This crisis experience provides the strongest argument yet for the need for a unified national framework, grounded not only in clinical efficacy but also in a shared ethical and legal foundation.

Towards a Unified National System: Reforms and Recommendations

The collective evidence from both operational challenges and crisis management points to a clear conclusion: the current state of Italian emergency triage, characterized by its regional variability, is no longer tenable for ensuring equitable and safe patient care. While local innovation has led to some commendable regional systems, the overall fragmentation and subjectivity are problematic. There are growing and consistent calls from academic and professional organizations for a reform that would make the system "more efficient and homogeneous throughout the country".

Moving forward, a comprehensive reform must be a multi-faceted endeavor that addresses the clinical, technological, and political dimensions of the problem.

Recommendation 1: Adopt a National Triage Standard. The most fundamental step is to establish a single, national triage framework. This should be based on a validated 5-level model, given the documented evidence that it can improve patient safety by reducing under-triage and better stratifying patient acuity. A unified system would ensure that a patient presenting with the same symptoms receives the same priority code, regardless of their location, thereby addressing the core issue of variability and equitable access to care.

Recommendation 2: Integrate Technology to Reduce Bias. The high degree of subjectivity in triage assignments is a direct consequence of the reliance on human judgment. Future reforms should explore the integration of technology, such as Machine Learning (ML) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), to enhance the accuracy and consistency of patient classification. Studies have identified vital signs, chief complaints, and patient demographics as key predictive variables that can be leveraged by such algorithms to support triage nurses in their decision-making process.

Recommendation 3: Mandate Standardized and Continuous Training. The successful implementation of any new national standard is contingent on the expertise of the staff. The example of the Manchester Triage System (MTS) in Merano highlights the importance of dedicated training, coaching, and a minimum level of experience for triage nurses. A national system must be supported by a robust, mandatory training and certification program to ensure that all triage nurses across the country are applying the new standards consistently and reliably.

Recommendation 4: Address the Underlying Political Structure. A purely clinical or technological solution will be insufficient without addressing the political roots of the problem. Italy's decentralized healthcare system, while a source of regional flexibility and innovation, is also the cause of its fragmentation and inequity. The ongoing political debate over "differentiated autonomy," which would grant regions even greater powers over healthcare and personnel management, poses a direct threat to any national standardization effort. For a national triage system to be successfully implemented and sustained, policymakers must find a way to balance regional autonomy with the fundamental constitutional right to a uniform and equitable level of healthcare for all citizens. The COVID-19 experience provides a powerful and tragic illustration of the consequences of failing to do so.

In conclusion, the Italian triage system is at a critical juncture. The legacy of its decentralized structure has allowed for pockets of innovation but has also created a landscape of inconsistency, inefficiency, and inequity. The lessons of the recent pandemic have made it clear that a cohesive, nationally standardized framework is not merely a matter of efficiency but of fundamental public safety and ethical responsibility. A successful reform must therefore move beyond individual hospital protocols and embrace a unified vision that leverages technology, mandates training, and, most importantly, reconciles the political imperatives of regional autonomy with the universal need for a just and equitable healthcare system.