Battlefield Triage: From Napoleonic Innovation to Modern Combat Care

This article traces this transformative trajectory, highlighting the foundational contributions of pioneers such as Dominique-Jean Larrey and Jonathan Letterman, the profound impact of the "Golden Hour" concept, and the revolutionary integration of modern technologies including artificial intelligence, wearable sensors, and advanced surgical capabilities.

The evolution of battlefield triage systems represents a remarkable journey of medical adaptation and innovation, driven by the relentless demands of warfare. From the rudimentary post-battle collection of the Napoleonic era to the highly sophisticated, technology-driven, real-time care systems of today, the core imperative has remained consistent: to maximize soldier survival and facilitate a return to duty. This report traces this transformative trajectory, highlighting the foundational contributions of pioneers such as Dominique-Jean Larrey and Jonathan Letterman, the profound impact of the "Golden Hour" concept, and the revolutionary integration of modern technologies including artificial intelligence, wearable sensors, and advanced surgical capabilities. The continuous refinement of triage protocols, evacuation strategies, and field hospital organization underscores a persistent, dynamic interplay between medical science, military strategy, and ethical considerations, ultimately shaping both military and civilian trauma care.

The term "triage" refers to the critical process of sorting casualties based on the severity of their injuries, a necessary measure when medical resources are overwhelmed. This systematic prioritization ensures the most effective allocation of limited care, aiming to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of individuals. The etymological root of "triage" stems from the French word "trier," meaning "to sort," a term initially applied to agricultural products such as coffee. Its first documented medical application, specifically for the classification of casualties, emerged during World War I.

Historically, battlefield medicine was characterized by disarray and exceptionally high mortality rates. Before the establishment of organized medical systems, wounded soldiers were frequently left where they fell, to be gathered only after the cessation of hostilities, or they relied on haphazard, untrained civilian efforts for evacuation. This often resulted in critical delays of 24 to 36 hours, and sometimes even days, before any medical attention was rendered. Such prolonged delays significantly increased the risk of severe complications, including tetanus, sepsis, and preventable deaths from uncontrolled hemorrhage. The inherent brutality and mass casualties inflicted by warfare created an undeniable and urgent demand for the development of more systematic and efficient medical responses.

This report chronologically traces the evolution of battlefield triage systems, examining how triage protocols, evacuation methods, and field hospital organization have transformed from the Napoleonic Wars to contemporary conflicts. Each historical period highlights key innovations, persistent challenges, and the enduring principles that continue to shape military medical practice.

The foundational concept of prioritizing care based on immediate medical need and potential for survival predates the formal adoption of the term "triage" by over a century. Dominique-Jean Larrey, a prominent French surgeon during the Napoleonic Wars, pioneered a system of sorting casualties according to the severity of their wounds, irrespective of rank or social standing. While his methods were revolutionary and effectively established the principles of modern triage, the term itself did not enter the medical lexicon until World War I. This distinction underscores that fundamental humanistic and pragmatic considerations—the urgent need to save lives and optimize scarce resources—often drive groundbreaking innovations in practice long before formal terminology or universally standardized protocols are established. The underlying principle of "doing the greatest good for the greatest number" was intuitively applied by early pioneers like Larrey, demonstrating that the evolution of medical practice is frequently a needs-driven process that is later codified and formalized. This also highlights how the practical demands of warfare often outpace the development of a unifying medical language.

Pre-Larrey Chaos and High Mortality

Prior to the reforms instituted by Dominique-Jean Larrey, the conventional military medical practice dictated that wounded soldiers be left on the battlefield until the conclusion of hostilities, or that their evacuation be haphazardly managed by untrained and disorganized civilians. This approach often led to critical delays in care, ranging from 24 to 36 hours, and in many cases, days, before any treatment was provided. Such delays placed soldiers at severe risk from complications like tetanus, sepsis, and, most commonly, death from uncontrolled hemorrhage.

Evacuation methods were rudimentary and highly inefficient. Large, cumbersome wagons, often drawn by as many as fifteen horses, were commonly used. These vehicles lacked suspension or padding, causing excruciating pain for the wounded during transport. Furthermore, they were typically positioned far from the battlefield, sometimes a league or more away, further exacerbating treatment delays. The process of moving casualties was also manpower-intensive, often requiring six to eight men to carry each wounded soldier and his belongings, which severely depleted fighting strength. During this period, officers frequently received preferential treatment, being afforded more comfortable forms of transport when available.

Dominique-Jean Larrey's Revolutionary Innovations: "Ambulance Volante" and Early Triage Principles

Dominique-Jean Larrey (1766–1842), Napoleon's chief surgeon, is widely recognized as the "father of modern military medicine" and "the father of emergency medical services" due to his profound innovations. Observing that wounded soldiers often did not receive care for up to 36 hours, Larrey developed dozens of medical innovations during his service in the French military.

Inspired by the rapid mobility of the French flying artillery, Larrey conceived and implemented the "ambulance volante," or "flying ambulances," system. These were light, horse-drawn carriages, with specialized two-wheeled designs for flat terrain and four-wheeled designs for rough terrain. Crucially, they were equipped with springs and padded interiors to provide greater comfort for patients during transport. These mobile units carried essential medical supplies, including food, bandages, water for wound washing, and the capability for "on the spot surgery". Larrey's system fundamentally altered evacuation by enabling rapid transport and immediate surgical intervention directly on the battlefield, often under fire, thereby drastically reducing the time between injury and initial medical attention.

A cornerstone of Larrey's reforms was his strong advocacy for a modern system of battlefield triage. He insisted that the wounded be treated based solely on the severity of their injuries, without regard to rank or nationality. He categorized casualties into three groups: those with 'trivial' injuries were treated quickly and returned to the front line; those with 'treatable' but more serious injuries were stabilized sufficiently for transport to a base hospital; and those with 'terrible' injuries, or little chance of recovery, were given pain relief and attended to after the other categories. His ambulance units were highly organized, comprising divisions of 113 men, including a chief surgeon, other surgeons, and personnel responsible for instruments and dressings.

Evolution of Field Surgical Practices and Mobile Dressing Stations

Larrey's system established mobile treatment centers and makeshift dressing stations as the first points of care. Seriously wounded soldiers received initial treatment on-site before being transported to larger field hospitals for further care. Surgical procedures, such as rapid amputation and debridement of wounds, were performed directly on the battlefield. While anesthesia was not yet available, Larrey introduced significant improvements in hemorrhage control, favoring ligatures over the traditional, brutal practice of cauterization with hot irons or boiling oil. Despite these advancements, surgeons often delayed major surgeries, believing patients needed time to recover, a practice that frequently resulted in death from infection or blood loss.

The approach taken by Larrey, emphasizing rapid forward care, represented a fundamental shift from passive casualty management to active, immediate intervention. Before his innovations, the norm was to leave wounded soldiers on the battlefield until the fighting ceased, essentially abandoning them to their fate or a delayed, haphazard collection. Larrey's "ambulance volante" fundamentally altered this by bringing medical care directly to the battlefield and initiating evacuation during or immediately after combat. This was not merely about faster transport; it represented a profound conceptual transformation. This shift established the foundational principle of "time to definitive care"—a concept that would later evolve into the "Golden Hour"—as paramount in military medicine. It recognized that effective, rapid medical intervention was not just a humanitarian effort but a critical force multiplier, preserving fighting strength and significantly boosting soldier morale by assuring them they would not be left to die. This early recognition of the tactical value of rapid medical response laid the groundwork for all subsequent advancements in military medical logistics and care.

Larrey's insistence on treating casualties based solely on the severity of their wounds, "without regard to rank or nationality" , was a radical departure from the common practice of preferential treatment for officers and the neglect of enemy combatants. This principle, while seemingly straightforward in its humanitarian intent, implicitly laid the groundwork for complex ethical debates that persist in modern military triage, particularly concerning "reverse triage" and the prioritization of one's own soldiers over others. Larrey's ethical stance was not purely humanitarian; it was also pragmatically driven by the desire to ensure that the most critical cases received attention for the maximum survival benefit, thereby preserving more lives overall. The enduring tension between universal medical ethics (treating all equally based on medical need) and military objectives (preserving fighting force, partiality to one's own troops) can be traced directly back to these early foundational principles. This complexity underscores that battlefield medicine is not a purely clinical endeavor but is deeply intertwined with military strategy, ethical philosophy, and the inherent moral compromises of warfare.

Initial Challenges and the Need for Structure

At the outset of the American Civil War, military medical care and evacuation were largely unorganized. Wounded soldiers frequently lay on battlefields for up to three days with minimal or no care. Hospitals, particularly in urban areas, were often viewed as places where the indigent went to die, and military surgeons commonly lacked sufficient training and experience with combat injuries, especially gunshot wounds.

The introduction of new, more lethal weaponry, such as the conoidal-shaped Minié ball and rifled cannons, inflicted far more devastating injuries than previously seen, crushing bones and creating large, complex wounds that overwhelmed the rudimentary medical capabilities of the time. The sheer scale of casualties in major battles, such as Gettysburg with 51,000, Chickamauga with 36,624, and Antietam with 22,717, highlighted the urgent need for systemic reform. Compounding these challenges was a widespread lack of proper sanitation and sterilization, as germ theory had not yet been widely adopted. This led to rampant wound infections and the uncontrolled spread of disease in overcrowded, unhygienic camps.

Dr. Jonathan Letterman's Plan: Organized Evacuation and Tiered Triage

A pivotal shift occurred on July 4, 1862, with the appointment of Major Jonathan Letterman as Medical Director for the Army of the Potomac. Letterman's comprehensive reorganization of the Medical Corps, known as the "Letterman Plan," became the standard for military wounded care delivery through World War II.

The plan's key components included the establishment of a dedicated, organized ambulance corps staffed with specifically trained personnel. It also mandated the standardization of medical tools and supplies at field dressing stations and placed a strong emphasis on rapid evacuation to field hospitals where emergency surgeries could take place. The first critical stop in Letterman's system was the field dressing station, positioned as close to the battlefield as tactically feasible, where initial triage was performed.

Casualties were sorted into four distinct categories:

Severe: Included serious bleeding, compound fractures, missing limbs, or major trauma. These patients received immediate first aid and were promptly evacuated by ambulance to the nearest field hospital for urgent care.

Mild: Encompassed excessive bleeding with the patient in stable condition. These individuals were evacuated after all severely wounded patients had been removed from the battlefield.

Slight: Referred to minor injuries that could be treated quickly, allowing patients to be sent back to their units, thereby preserving fighting strength.

Mortal: Represented the lowest priority, including wounds that pierced the trunk of the body or head. These patients were made as comfortable as possible and set aside, as the medical knowledge and technology of the era were insufficient to treat such injuries.

This systematic approach, though not yet using the formal term "triage" , dramatically improved soldiers' chances of survival and instilled a crucial sense of assurance that they would not be abandoned on the battlefield.

Development of a Comprehensive Hospital System (Field to General)

Letterman's plan established a multi-tiered hospital system that provided a continuum of care, from mobile and field hospitals near the front lines to brigade, general, specialty, and rehabilitation hospitals further to the rear. Tent hospitals were rapidly prepared and set up at major battlefields like Gettysburg and at way stations. By the end of 1863, well-ventilated, multiple-pavilion style hospitals, some accommodating up to 3,000 patients, were being constructed in major cities. By war's end, the Union Army alone operated 204 general hospitals with over 136,000 beds.

The war also spurred the creation of specialty hospitals, such as Turner's Lane in Philadelphia for neurologic diseases and Desmarres Hospital in Washington, D.C., for eye and ear conditions. Advances in the administration of anesthesia and the development of new surgical techniques, including early facial reconstruction, emerged. The significant number of amputees resulting from the war also spurred crucial improvements in prosthetic technology.

The explicit connection between advancements in weaponry and the subsequent evolution of medical systems is a recurring pattern in military history. The Civil War's "advancements" in weapons technology, particularly the Minié ball and rifled cannon, led to significantly more severe, complex, and numerous injuries compared to previous conflicts. This unprecedented scale and severity of casualties directly overwhelmed the existing, disorganized medical capabilities. The sheer magnitude of human cost forced the rapid development and formalization of a structured, comprehensive medical system under Dr. Jonathan Letterman. This demonstrates a critical dynamic: while designed for destruction, advancements in weaponry inadvertently act as a powerful and often brutal catalyst for medical innovation and systemization. The increasing severity and volume of injuries necessitate a more organized, efficient, and technologically capable medical response, driving a continuous and reactive cycle of adaptation and improvement in battlefield care.

Letterman's plan was not a mere collection of isolated improvements but a comprehensive, integrated system. It encompassed organized ambulance corps, tiered triage protocols, standardized supplies, and a networked hierarchy of hospitals ranging from mobile field units to general and specialty facilities. This "threading the wounded and diseased through a series of continuously improving treatments and rehabilitation" represented a fundamental shift from fragmented medical acts to a coordinated continuum of care. This marked a crucial evolution from Larrey's pioneering efforts by establishing a truly systemic approach, recognizing that patient survival and recovery depend not just on initial treatment but on a seamless progression through various, increasingly specialized levels of care. This laid the essential groundwork for modern echelons of care (Role 1-4) and the broader concept of a "trauma system" , emphasizing the interconnectedness and interdependence of pre-hospital, field, and definitive care phases.

The Emergence of "Triage" as a Medical Term and Standardized Protocols (Depage's Ordre de Triage)

The term "triage," derived from the French "trier" (to sort), was formally adopted for medical use in World War I by the French and quickly integrated into British military medical lexicon. A significant advancement came with Antoine Depage in 1914, who introduced the five-tiered "Ordre de Triage," a systematic evacuation protocol that established specific benchmarks for staged casualty evacuation.

Casualties were typically classified into three categories: "minimally wounded" (treated quickly and returned to the front line to maintain fighting strength), "seriously wounded but treatable" (stabilized and transported to base hospitals for further care), and "mortally wounded" (given pain relief, usually opium or morphine, and prioritized last, to be seen only after others were cleared). This system was designed to direct scarce medical staff and resources to where they would be most effective. Triage and initial dressings were performed at clearing stations, with major or minor surgery generally avoided at these early stages of engagement. Evacuation was often conducted under the cover of darkness to avoid enemy fire.

Impact of Motorized Transport and Early Air Evacuation

The early 20th century marked a crucial transition from horse-drawn ambulances to motorized vehicles, which dramatically improved response times and overall operational efficiency. World War I saw the organization of professional ambulance services, implementing tiered levels of care from the front line through battalion aid stations to fully operational field hospitals, a system made feasible by the advent of motorized ambulances.

World War II further accelerated advancements in ambulance services, including the development of rudimentary air ambulances for rapid evacuation and the use of radio communication for improved coordination. Critically, cargo and troop carrier planes, often returning empty from the front lines, were repurposed as the only swift means of evacuating critically wounded patients to general hospitals located outside the immediate warzone. Initial air evacuation efforts in WWII were informal but rapidly demonstrated their immense value, particularly during campaigns like Tunisia. C-47 transport planes were rigged with litter racks to accommodate 18-20 non-ambulatory patients and staffed by Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadrons. These planes carried essential "evacuation kits" containing blood plasma, oxygen, morphine, portable heaters, and first-aid supplies. The chaotic and brutal realities of long-distance evacuation, as seen in the Crimean War (though preceding WWI), underscored the critical need for organized transport systems over rough terrain and sea journeys.

Adaptation of Triage and Care Levels in Mass Casualty Scenarios

The increased availability of airplanes during WWII allowed rapid evacuation to hospitals outside the warzone to become an integral part of the triage process. While basic practices remained consistent—initial evacuation to an aid station, followed by transitions to higher levels of care, and eventual admission to a permanent hospital—more advanced care was provided at each stage. Overall, medical treatments and knowledge advanced significantly during WWI, leading to a far greater chance of survival for soldiers injured in 1918 compared to 1914.

The formal introduction of the term "triage" and the development of standardized protocols like Depage's Ordre de Triage during World War I marked a maturation of military medical thinking. The explicit classification of casualties into "minimally wounded, seriously wounded but treatable, and mortally wounded" or "trivial, treatable, and terrible" directly linked medical care to the strategic objective of returning soldiers to the front line. This period signifies a shift beyond individual humanitarianism to a more formalized, strategic approach where triage became a critical tool for maintaining combat effectiveness and preserving manpower. The explicit categorization and prioritization reflect a calculated effort to optimize medical resources for the broader war effort, foreshadowing the later concept of "reverse triage" in extreme tactical situations.

The transition from horse-drawn to motorized ambulances dramatically improved the speed and efficiency of ground evacuation. Crucially, in World War II, cargo and troop carrier planes were repurposed for medical evacuation, often on their return flights from the front. This highlights an opportunistic, rather than purpose-built, initial adoption of air transport for medical purposes. This demonstrates that technological advancements, even when not initially designed for medical use, can be rapidly adapted and leveraged to revolutionize battlefield logistics. The early, informal use of aircraft for evacuation laid the critical groundwork for the later development of dedicated aeromedical evacuation platforms (such as helicopters in the Korean and Vietnam Wars), proving the concept of rapid air transport as superior for critically wounded cases and setting a new, higher standard for patient movement. This also points to the military's inherent adaptability and resourcefulness in leveraging available assets for critical needs.

Impact of Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH)

While precursors existed in World War II (Auxiliary Surgical Groups), the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) concept truly came of age and revolutionized trauma care during the Korean War. MASH units were strategically designed to provide emergency surgical care directly near the front lines, significantly reducing the critical time between injury and surgical treatment. This proximity to the battlefield dramatically improved survival rates for wounded personnel.

These units were mobile, typically tent-based facilities , equipped with approximately 60 beds and staffed by a dedicated team of surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, and support personnel. They performed essential emergency procedures such as controlling hemorrhage, debridement of wounds, and necessary amputations. The combined success of MASH units and the burgeoning aeromedical evacuation system was profound, cutting the mortality rate for injured soldiers in the Korean War by almost half, to an unprecedented 2.5%.

Role of Helicopter Evacuation and In-Flight Care

The Korean War marked the advent of helicopters (e.g., Bell H-13 Sioux, Sikorsky H-5, Hiller H-23) for medical evacuation (MEDEVAC), fundamentally revolutionizing battlefield operations. Although early models were fragile, high-maintenance aircraft with limited range and often no radios, their impact was immediate. Helicopters dramatically reduced evacuation times, enabling some casualties to reach MASH units within minutes of being wounded. This speed saved countless lives and significantly boosted troop morale, as soldiers knew help was never far away. Helicopters could land in confined spaces and operate under fire to reach forward aid stations.

While helicopters in the Korean War were primarily used for rapid transport, the Vietnam War saw further, crucial advancements: the introduction of helicopter medics who were capable of providing fluid resuscitation and other critical interventions mid-flight. This made the "golden hour" concept a practical reality, reducing the average time from injury to definitive care to less than two hours. The iconic "Dust Off" missions, often utilizing UH-1 Iroquois "Huey" helicopters, became synonymous with rapid and effective air ambulance services, landing frequently under fire to remove, treat, and transport the wounded.

Advancements in Trauma Management and Surgical Techniques

The Korean War brought significant improvements in medical understanding, particularly regarding the management of shock, which allowed for earlier and more effective interventions in the triage process. Triage categories (immediate, delayed, minimal, and expectant) developed during this period remain the basis for most modern triage systems today. In Korea, the widespread use of antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis meant that soldiers rarely died from infection, especially from extremity wounds. The chief causes of death shifted to hemorrhage and injury to vital organs. The focus of care therefore evolved to emphasize controlling hemorrhage and initiating blood transfusions before evacuation, particularly for casualties with reduced blood volume who tolerated movement poorly.

The Vietnam War further propelled advanced surgical techniques and improved medical management. Surgeons rediscovered the benefits of delayed wound closure (except for cranial, facial, and some hand injuries), which permitted necessary drainage and better healing. Vascular surgery, which was sporadic in Korea, became commonplace in Vietnam, with general and orthopedic surgeons routinely performing complex repairs. The "team approach" to surgery, involving multiple specialists operating together (e.g., neurosurgeon, ophthalmologist, oral surgeon, and plastic surgeon for head injuries), proved highly effective. The ready availability of whole blood, sometimes administered even before the arrival of an air ambulance, significantly contributed to the low mortality rate in Vietnam by better preparing the wounded for evacuation. Innovations such as styrofoam containers for field blood storage and the use of fresh frozen plasma for volume replacement and bleeding control were introduced. New anesthetic medications, such as Ketamine, ideal for hypovolemic trauma patients, were discovered and approved for medical use during this period. These advancements in wound management and patient care led to a considerable reduction in the average length of stay for patients in Vietnam compared to earlier conflicts.

The introduction of MASH units and helicopter evacuation during the Korean War was explicitly aimed at reducing the time to surgical treatment. The Vietnam War then formally codified this critical window as the "golden hour" , with helicopter medics providing in-flight care to achieve this benchmark. This wasn't merely an observed outcome; it became a design philosophy that permeated and shaped the entire military medical chain of evacuation and care. The "Golden Hour" concept transformed battlefield medicine from a reactive service to a proactive, time-sensitive system. It established rapid intervention and evacuation as the central tenets, influencing everything from the tactical placement of medical units (MASH close to the front) to the design of equipment (portable, in-flight capabilities) and the training of personnel (medics providing advanced pre-hospital care). This principle subsequently flowed into civilian emergency medical services , firmly establishing the military's role as a crucial incubator for trauma care innovation that benefits broader society.

The dramatic reduction in mortality rates observed during this era was not attributable to a single factor. Instead, it was the synergistic effect of multiple, converging advancements: the tactical deployment of surgical capabilities via MASH units (organizational innovation), the rapid transport technology of helicopters (technological innovation), improved understanding and management of shock and hemorrhage (advances in medical knowledge), and the ready availability of whole blood and new anesthetics (pharmacological advancements). Each of these elements amplified the effectiveness of the others. This period serves as a prime example of how a holistic approach, which integrates organizational structure, technological tools, and scientific understanding, is essential for achieving significant improvements in battlefield medicine. It highlights that no single innovation operates in isolation; rather, it is the strategic combination, refinement, and interoperability of multiple elements that lead to revolutionary outcomes in patient survival. This complex interplay continues to define and drive modern military medical research and development.

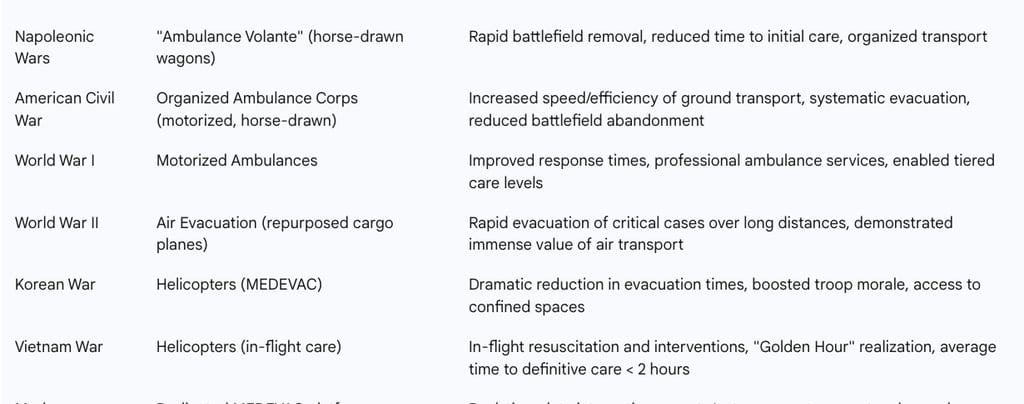

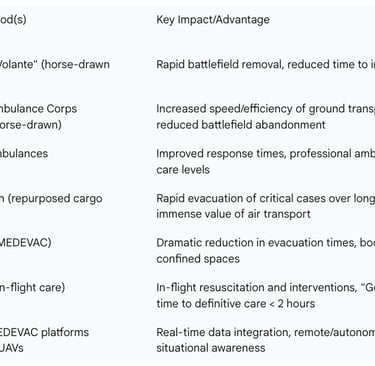

Key Innovations in Battlefield Evacuation Methods (Napoleonic to Modern)

Modern Battlefield Medicine: Contemporary Conflicts (21st Century)

Current Triage Protocols and Decision-Making Algorithms

Contemporary battlefield triage employs sophisticated protocols, with commonly accepted systems including START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment) and SALT (Sort-Assess-Lifesaving Interventions-Treatment/Transport). Triage is recognized as a fluid and dynamic process, with casualty categories subject to change based on evolving situations and available resources. This can even include "on-table triage," where a surgical operation might be abruptly terminated if a patient's condition deteriorates from "emergent" to "expectant".

Modern triage categories, often color-coded, closely mirror the historical classifications. These include Red (Immediate), Yellow (Delayed), Green (Minor), and Black (Deceased), which directly correspond to the Civil War categories of Severe, Mild, Slight, and Mortal wounds. Red/Immediate patients are the highest priority, requiring attention within minutes to two hours to prevent death or major disability. Military-specific triage systems frequently utilize T (Treatment) codes (T1, T2, T3, T4, and dead) or P (Priority) codes (P1, P2, P3, and P-hold) to classify injured individuals.

A unique and ethically complex aspect of modern military triage is the potential for "reverse triage" in extreme battle conditions. This protocol mandates treating the least wounded first so they can rapidly return to combat, creating a significant tension with conventional medical ethics that prioritize the most severely injured. This situation is often described as a "moral tragedy" for the military physician. Modern triage also incorporates special considerations for specific types of casualties: those contaminated in biological and/or chemical environments (requiring decontamination before treatment), patients with retained unexploded ordnance (who must be segregated immediately and treated last), and noncombatant local or third-country nationals (whose care is provided based on the mission, tactical situation, and medical necessity).

Echelons of Care: From Point of Injury (Role 1) to Definitive Care (Role 4)

Modern military medicine operates within an integrated health services support system, characterized by a progressive distribution of medical resources and capabilities across distinct "Roles of Care" (Roles 1-4). This continuum aims to triage, treat, evacuate, and return casualties to duty in the most time-efficient manner.

Role 1 (Unit-level Medical Care): This care is provided at or very close to the point of injury. It includes initial trauma care, forward resuscitation, and immediate lifesaving measures performed by first responders (self-aid/buddy aid) and combat lifesavers. Key interventions include stopping life-threatening external hemorrhage (e.g., with tourniquets and hemostatic dressings), maintaining airway patency, and preventing shock. This role typically does not include surgical care.

Role 2 (Advanced Trauma Management): A medical treatment facility (MTF) capable of receiving and triaging casualties, performing resuscitation, and treating shock at a higher level than Role 1 facilities. Role 2 routinely includes damage control surgery (DCS) capabilities and may offer limited, short-term holding for casualties until further evacuation can be arranged. These facilities can provide packed blood products, limited X-ray, and laboratory support. Role 2 Enhanced (2E) facilities offer more robust surgical modules.

Role 3 (Emergency & Specialty Surgery): This level provides major specialist facilities, including advanced diagnostic imaging (e.g., CT scanners), intensive care units, and extended holding and nursing capabilities. At this level, initial wound surgery and specialty surgeries (general, orthopedic, urogenital, thoracic, ENT, neurosurgical) are performed, along with post-operative treatment. Final sorting of casualties for transfer to Role 4 or return to duty typically occurs at Role 3 facilities.

Role 4 (Definitive Care): This represents the highest level of care, providing the full spectrum of definitive medical care, including highly specialized surgical and medical procedures, reconstructive surgery, and long-term rehabilitation. This care is typically provided in robust overseas facilities or home country base hospitals.

The overarching goal across these echelons is the rapid evacuation of casualties to progressively higher levels of care, ultimately aiming for return to duty or definitive recovery.

Evolution of Field Hospitals: Combat Support Hospitals (CSH) and Forward Surgical Teams (FST)

The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) units, which revolutionized care in Korea and Vietnam, were phased out by the U.S. Army in the early 2000s, replaced by the more advanced Combat Support Hospitals (CSH) and highly specialized Forward Surgical Teams (FST).

Combat Support Hospitals (CSH): As the successors to MASH, CSHs are significantly larger organizations, typically deploying with 44 to 248 hospital beds (most commonly 84), and staffed by over 600 personnel when fully deployed. They are transportable by aircraft and trucks in standard military cargo containers (MILVANs) and are assembled into tent hospitals. A key operational advantage of the Deployable Medical Systems (DEPMEDS) facility is the use of single or double expanding ISO containers to create hard-sided, climate-controlled, sterile operating rooms and intensive care facilities, capable of producing surgical outcomes comparable to fixed-facility hospitals. CSHs provide their own power from generators and include pharmacy, laboratory, X-ray (often with CT scanners), and dental capabilities. Due to their size and relative immobility, CSHs are not the front line of battlefield medicine but serve as a critical bridge, receiving most patients via helicopter air ambulance and stabilizing them for further treatment at fixed facilities.

Forward Surgical Teams (FST): These are small, highly mobile surgical units, typically comprising 20 staff members including surgeons, registered nurses, certified registered nurse anesthetists, licensed practical nurses, surgical technicians, and medics. An FST can establish a functional operating room within 1.5 hours of arrival on scene and can break down and move to a new location within two hours of ceasing operations. Their primary mission is to perform damage control surgery on combat casualties within the "golden hour" of injury, providing a surgical capability at the Role 2 level for patients who might not survive evacuation to a Role 3 hospital. FSTs are designed for continuous operations for up to 72 hours with a planned caseload of 30 critical patients and can even split into two independent teams to cover a wider area.

The evolution from MASH units to the current Combat Support Hospitals (CSH) and particularly the Forward Surgical Teams (FST) signifies a strategic and continuous push to decentralize advanced surgical capabilities. While CSHs are larger and less mobile, FSTs are small, highly mobile units specifically designed to provide damage control surgery within the critical "golden hour" at the Role 2 level. This represents a significant shift, bringing sophisticated intervention much closer to the point of injury than ever before. This trend reflects a continuous optimization for speed and initial stabilization, recognizing that early, targeted surgical intervention can prevent irreversible deterioration during evacuation. It implies a paradigm shift from simply transporting patients to definitive care to initiating definitive care as early as possible on the battlefield. This also necessitates a higher level of training, autonomy, and specialized equipment for frontline medical personnel, blurring the lines between pre-hospital and hospital-level care.

Technological Integration: Wearable Sensors, AI/ML, Telemedicine, and Advanced Prosthetics

Technological advancements are profoundly shaping modern military medicine.

Wearable Sensors: Military medicine increasingly leverages wearable sensors to continuously monitor the health and readiness of service members. These devices provide real-time data on vital signs such as heart rate, ECG, respiration, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and core body temperature, as well as indicators of heat strain, altitude sickness, fatigue, illness, and trauma. Algorithms process this physiological data to indicate risk levels, potentially aiding in automated triage and informing critical medical decisions in the field.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): AI and ML are transforming battlefield medicine by enhancing the speed and accuracy of patient assessment, identification, and tracking. AI-driven command systems facilitate real-time casualty tracking, triage, and decision-making in complex scenarios, helping to manage information overload. AI-powered software, such as the Battlefield Assisted Trauma Distributed Operations Kit (BATDOK®) and its enhancement FORGE-IT, creates seamless electronic medical records from the point of injury through recovery, enhances remote patient monitoring, and provides clinical decision support to warfighters. Furthermore, institutions like MIT are developing AI/ML solutions to streamline military MEDEVAC and mass casualty operations by combining patient data to support clinicians and airlift planners.

Telemedicine: Advances in telemedicine improve real-time communication and enhance awareness of medically related information across the battlefield. Secure video conferencing and audio-only telemedicine visits are now covered services. Telemedicine allows mental health providers to consult with or supervise one another and enables patients to attend appointments remotely, eliminating travel barriers. Platforms like the Team Awareness Kit (TAK) integrate into existing medical infrastructure to provide a global view of resources, patient movement, and direct communication, significantly reducing the "fog of war" related to battlefield injury and evacuation.

Advanced Prosthetics: Significant advancements in prosthetic technology over the past two decades have dramatically transformed the landscape for service members who experience limb loss. Modern military policy and medical capabilities now offer pathways for these individuals to continue military service. State-of-the-art prosthetic limb technology, including myoelectric prosthetics for computer interface work, activity-specific terminal devices, and lightweight carbon fiber components, enables amputees to perform a wide range of roles from combat support to administrative positions. Rehabilitation facilities, such as Walter Reed's Military Advanced Training Center (MATC), utilize sophisticated prosthetics and cutting-edge athletic equipment, including virtual reality systems like CAREN, to facilitate comprehensive rehabilitation and return service members to the highest possible level of physical, emotional, and psychological function.

The integration of wearable sensors providing real-time bio-data , AI/ML algorithms analyzing this data for triage and decision support , telemedicine enabling remote consultation and command/control , and systems like BATDOK® creating electronic records integrated with broader DoD platforms collectively represent a profound shift. This entire ecosystem is dedicated to the rapid collection, analysis, and dissemination of medical data across all echelons of care. This signifies the emergence of "data-driven" battlefield medicine. Real-time information flow dramatically reduces the "fog of war" in medical logistics , enables predictive analytics for more accurate and faster triage , optimizes resource allocation, and allows for continuous patient monitoring from the moment of injury through recovery. This interconnectedness not only enhances individual patient outcomes but also provides commanders with unprecedented situational awareness regarding the medical readiness and status of their forces, highlighting the increasing convergence of medical science and information technology.

Ethical Considerations and Challenges in Modern Triage

Modern battlefield triage, particularly in mass casualty scenarios where resources are severely overwhelmed, continues to grapple with complex ethical dilemmas. A persistent tension exists between the conventional medical ethical principle of treating the most severely wounded first, without discrimination based on rank or nationality (as advocated by Larrey and enshrined in the Geneva Conventions), and the pragmatic military objective of preserving fighting force. This tension is most acutely manifested in the practice of "reverse triage," where the least wounded are prioritized for rapid treatment to return them to combat quickly.

The World Medical Association's Declaration of Tokyo and Article 12 of the Geneva Conventions explicitly state that medical decisions should be based solely on medical criteria, without discrimination. However, some arguments propose "associative duties," suggesting that military personnel have ethical obligations of friendship and solidarity to their own group, which may justify partiality in triage. This creates a profound "moral tragedy" for military physicians, who may be forced to make decisions that, while tactically defensible, inherently betray or violate important values such as justice, compassion, and respect for others. Such choices are inherently difficult and stressful, leading to ongoing moral distress for medical personnel. Larrey's foundational principle of treating "without regard to rank or nationality" established a core medical ethic of impartiality. However, modern military triage, particularly the concept of "reverse triage" , explicitly prioritizes returning soldiers to combat or favoring one's own forces, which directly contradicts this impartiality. This situation is labeled a "moral tragedy" , where virtuous physicians are forced to make difficult choices that compromise core values. This reveals that despite centuries of medical advancements and the formalization of ethical guidelines, the fundamental ethical conflict inherent in battlefield medicine remains unresolved. The military physician operates within a dual loyalty system—to the individual patient and to the military mission/force. This tension is magnified in mass casualty events where resource scarcity forces agonizing choices. The "moral tragedy" concept suggests that some decisions, while tactically necessary for the war effort, are inherently ethically compromising, leading to ongoing psychological and moral burdens for medical personnel. This also points to the critical need for robust ethical frameworks, training, and support systems for military medical professionals operating in these complex environments.

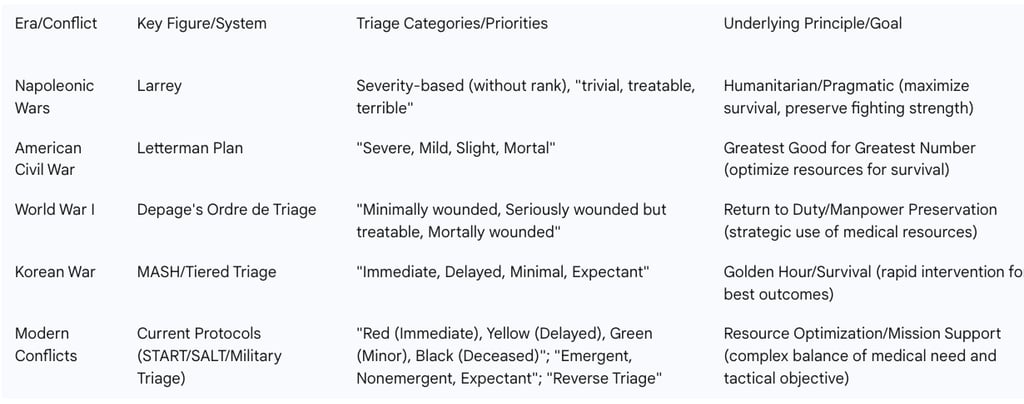

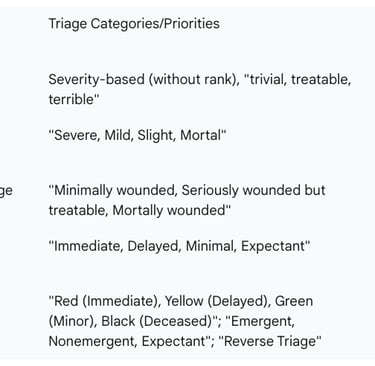

Table 1: Evolution of Battlefield Triage Categories (Napoleonic to Modern)

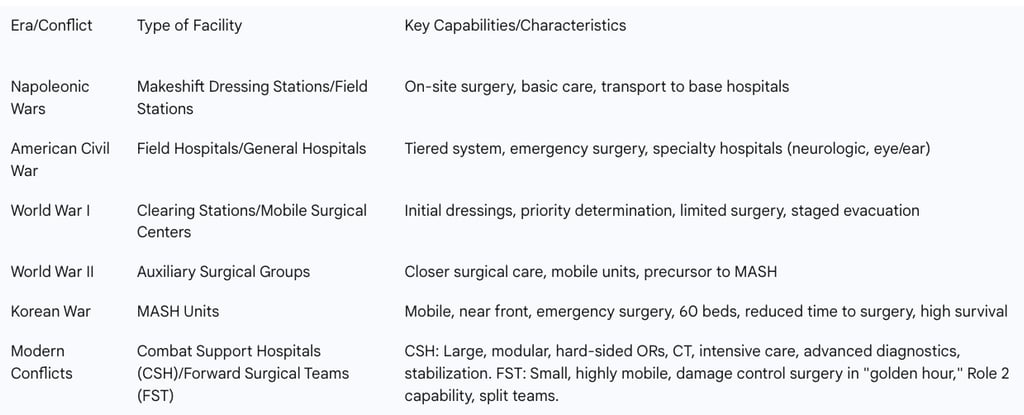

Table 3: Progression of Field Hospital Organization and Capabilities (Napoleonic to Modern)

Conclusion

The evolution of battlefield triage systems, from the Napoleonic Wars to modern conflicts, reveals several enduring principles that have consistently guided military medical practice. The paramount importance of rapid evacuation, first championed by Larrey's "ambulance volante," has remained a constant driving force, culminating in the "Golden Hour" concept. The prioritization of care based on injury severity, albeit with variations like "reverse triage" influenced by tactical objectives, has consistently guided resource allocation. Furthermore, the continuous adaptation of medical organization and practices in response to evolving weaponry and battlefield demands underscores the dynamic nature of military medicine.

The future of battlefield medicine will likely see an accelerated integration of advanced technologies. This includes further development and widespread deployment of artificial intelligence and machine learning for enhanced triage accuracy, predictive analytics in medical logistics , and autonomous systems like Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for casualty evacuation and supply delivery. Wearable sensors will provide increasingly sophisticated real-time physiological monitoring, potentially enabling automated triage and continuous health assessment. Telemedicine will expand its role in remote consultation, surgical guidance, and command and control, bridging geographical distances and enhancing expert collaboration. Continued advancements in surgical techniques, resuscitation, and advanced prosthetics will further improve patient outcomes and rehabilitation capabilities.

Despite these advancements, significant challenges persist. The ethical dilemmas inherent in battlefield triage, particularly the tension between medical impartiality and military necessity, will continue to require careful consideration and robust ethical frameworks. Ensuring the adaptability and resilience of medical systems in diverse and unpredictable conflict environments remains crucial. Moreover, addressing the psychological toll on medical personnel who consistently operate in high-stress, ethically ambiguous situations will be an ongoing concern.

It is imperative to acknowledge the profound and continuous spillover of military medical innovations into civilian trauma care and emergency medical services. From organized ambulance systems and tiered triage protocols to air ambulances and advanced trauma management techniques, the battlefield has historically served as a critical laboratory for medical advancements that ultimately save countless lives in civilian contexts worldwide.